Water Bandits

How one company almost got away with draining the Mojave Desert

Water Bandits

How one company almost got away with draining the Mojave Desert

March 26, 2021

Part of the Earthjustice experience is winning in court only to have a company come back with another way to get what they want at the expense of the environment.

This is the story of how we stopped a company from draining the Mojave Desert. And it's also a story about how they are back, trying it again, and we are meeting them once again with a lawsuit. More on the new lawsuit in the epilogue. First, here's the story of Round 1:

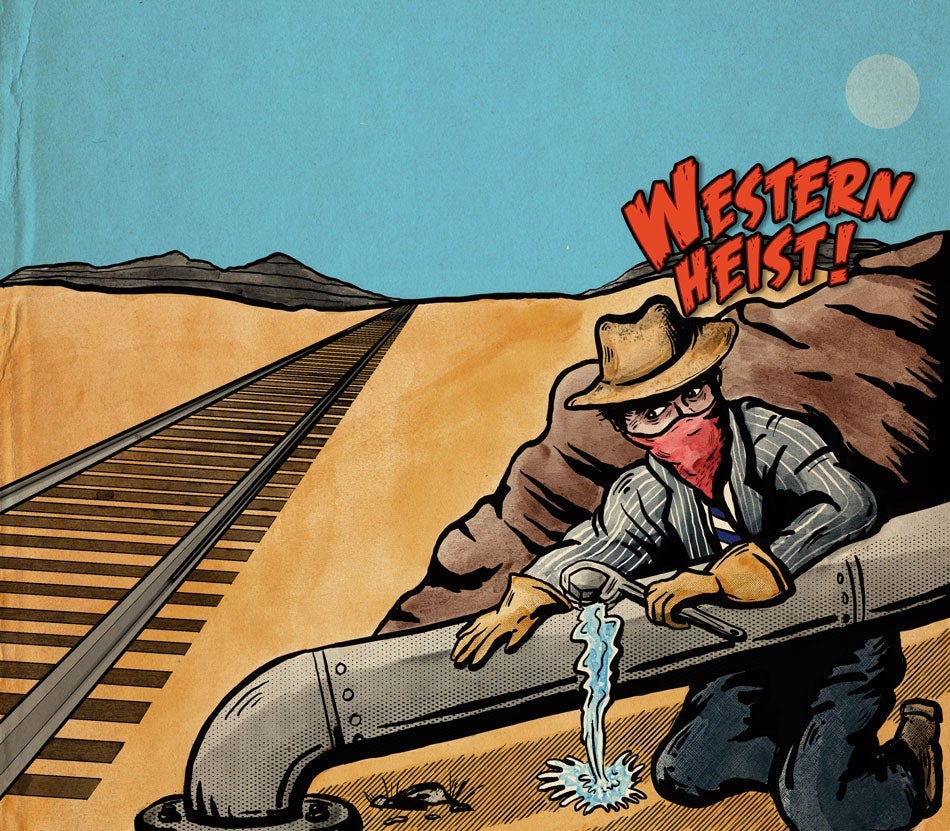

The Mojave Desert was once the place to be if you wanted to rob a train.

Amid the sand dunes and salt flats that occupy California’s southeastern tip, summer temperatures hover above 100 degrees, and railcars trundle along far from human settlement. In the 1900s, outlaws waited by the isolated tracks to waylay locomotives.

Recently, a company called Cadiz, Inc., tried a different kind of railroad heist in the Mojave. Cadiz hatched a plan to wring contaminated groundwater from the desert and sell it to the residents of suburban Los Angeles, despite the destruction the project would wreak on nearby public lands. With an assist from the Trump administration and an old railroad statute, the corporation almost got away with it.

Our Clients Center for Biological Diversity, Center for Food Safety

Thankfully, the arm of the law is longer today than it was a century ago. Representing environmental and public health groups, Earthjustice was able to stop Cadiz in its tracks.

Ileene Anderson has been tracking Cadiz’s Mojave plan for years, even when the project seemed like a desert mirage.

Anderson, a public lands director and senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, visits the desert regularly to look for rare plants and animals. Setting out from her Los Angeles home, she weaves through traffic until the highways give out, then bounces along dirt roads through the shimmering heat.

“In the minds of some people, these are wastelands because there aren’t beautiful forests on them, and, you know, babbling brooks and all that,” she says.

Anderson knows better.

“If you go out during the spring, the wildflowers can sometimes carpet the ground with just gaudy colors,” she says. “It’s a really incredible experience to see the amount of life that is there.”

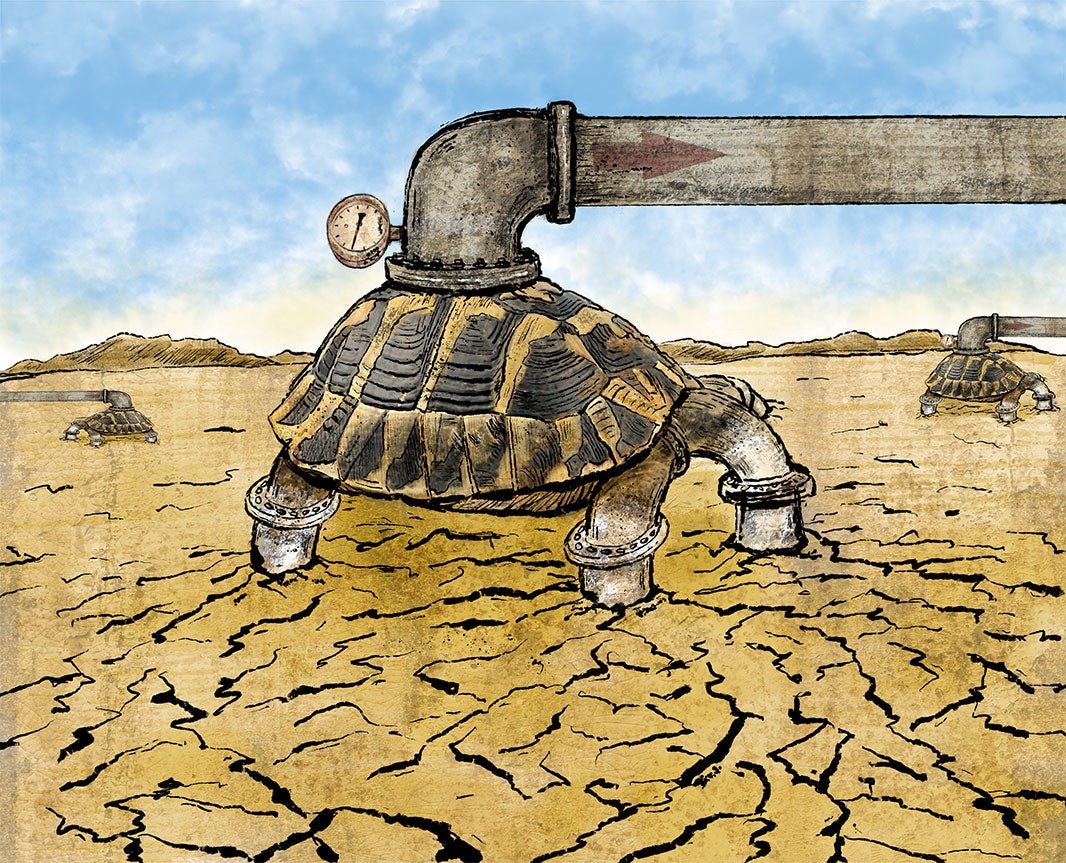

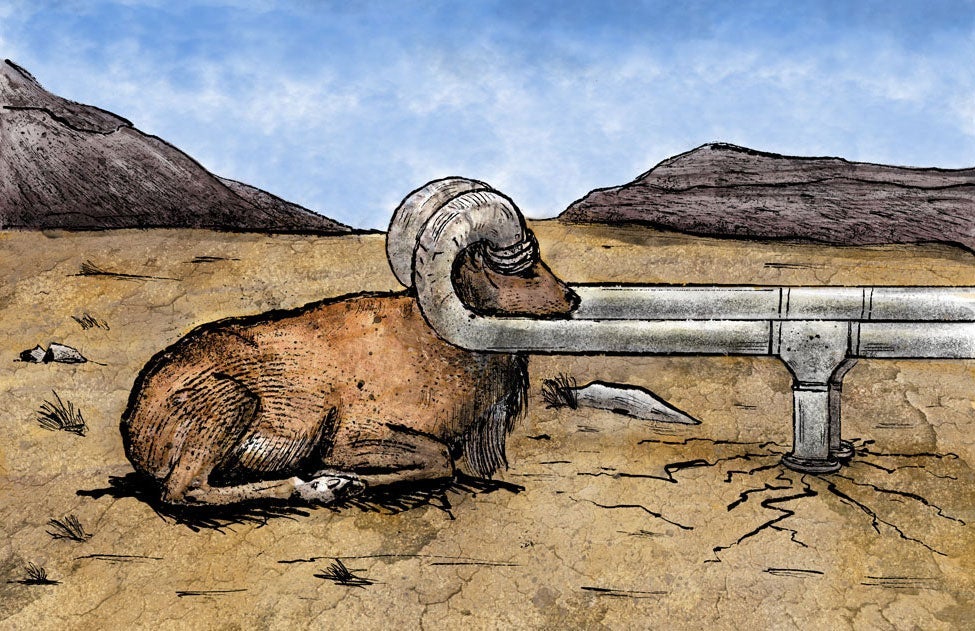

One big reason the Mojave is not a lifeless wasteland is Fenner Basin, a 700-square-mile aquifer beneath the desert. It connects to freshwater springs and riparian vegetation, which nourish bighorn sheep, tortoises, and migratory birds as they cross the dunes.

Cadiz has been trying to tap Fenner Basin for more than two decades. The company owns 34,000 acres of private property within Mojave Trails National Monument, just north of Joshua Tree National Park. If Cadiz could secure the necessary approvals from local, state, and federal officials to pipe the aquifer’s contents out along an old railroad right-of-way, it could rake in billions of dollars by selling the water to municipal water districts in coastal Southern California.

The reason the company has struggled to make that happen is that draining the aquifer would also drain much of the life from the Mojave. For many years, government agencies rightfully balked at the project’s unacceptable environmental costs.

Then the tables turned. One of Cadiz’s former attorneys landed a prime spot in the Trump administration. Soon after, the project got the green light from the Bureau of Land Management.

“It was just so obvious that the fix was in politically,” Anderson says. “It was really, really frustrating.”

The Center for Biological Diversity contacted Earthjustice about suing the Trump administration. Together, we went to court to bring law and order to the desert.

In his almost 20 years at Earthjustice, attorney Greg Loarie has focused on litigation concerning Northern California, where he grew up. But when the Cadiz project crossed his desk in mid-2017, he knew he wanted to lead the lawsuit against it.

It wasn’t just that Loarie had fallen in love with Southern California deserts during his undergraduate years at UC San Diego. He was also excited about a legal question at the heart of the case.

“It’s not every day that you get to argue over the proper meaning of a statute enacted almost 150 years ago,” he says. That statute was the General Railroad Right of Way Act, which Congress passed in 1875 to hasten rail expansion of the “western frontier.” The law gave railroad companies property rights on public lands up to 100 feet on each side of a rail line.

“People aren’t building a lot of new trains anymore, so the question for the railroads is, ‘What else can we do with these fairly valuable rights-of-way?’” Loarie says. One answer is that the railroads can try to lease their rights-of-way to other corporations.

An old set of tracks owned by the Arizona and California Railroad happened to run through the area where Cadiz wanted to build its pipeline. If Cadiz could construct its pipeline along these tracks, the company concluded it would not need to submit its proposal to the Bureau of Land Management for an environmental review, because it would technically be operating on railroad property.

The too-clever scheme quickly hit a setback. In 2011, lawyers at the Department of the Interior — the agency that oversees the Bureau of Land Management — prepared a memo that analyzed the hot topic of railroad easements. Based on the entire history of the 1875 Railroad Act, they concluded that in order for anyone to build or do business along a railroad right-of-way, their activities must have something to do with running a railroad.

Faced with this problem, Cadiz dreamed up some solutions. The company claimed that its project would serve a “railroad purpose” by providing water to a steampowered tourist train that doesn’t currently exist. Cadiz also promised to construct sprinklers along the existing railroad trestles, just in case one of them ever caught fire — something the trestles had managed to avoid doing for almost a century.

“Cadiz’s so-called ‘railroad purposes’ appear to be window dressing meant to disguise a commercial water project that bears no legitimate relation to a railroad,” Loarie says. The Bureau of Land Management wasn’t convinced either.

In 2015, it ruled that Cadiz could not use the Railroad Act to dodge the environmental review process.

Things didn’t look good for the company. But then, Donald Trump became president — and nominated David Bernhardt for a leading role in the Interior Department.

Bernhardt joined the Trump transition team after several years as a partner and shareholder at the lobbying and law firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, where his clients happened to include Cadiz. He had represented the company during the fight to build the pipeline. Brownstein even owned a financial stake in Cadiz and stood to profit off the pipeline project.

A few weeks after Trump’s election, Bernhardt left the transition team and temporarily returned to Brownstein. Just after his departure, the Trump team included Cadiz on a priority list of “emergency and national security projects.” Then in April 2017, Trump nominated Bernhardt to serve as Deputy Secretary of the Interior.

Bernhardt maintains he never played a role in the administration’s decisions about the pipeline project. After being confirmed for his post, he recused himself from department work on Cadiz and withdrew from the Brownstein partnership.

But by then, the train had left the station. In September 2017, the Department of the Interior issued a new memo that reversed its previous reading of the Railroad Act. Now it claimed that railroads could lease their rights-of-way to anyone as long as their activities did not interfere with a railroad purpose.

The next month, the Bureau of Land Management exempted the Cadiz project from environmental review. After 20 years, the company’s train was coming in.

Living in Glendale, California, a few miles down the road from Ileene Anderson, Maria Juur had her own concerns about the Cadiz project.

Juur, a social media manager at the Center for Food Safety, knew that the water Cadiz wanted to tap potentially contained dangerous levels of hexavalent chromium. This toxic compound occurs naturally in certain rocks and soils, and it has been linked to cancer in humans. In the 2000 biopic “Erin Brockovich,” hexavalent chromium is the chemical that poisons the residents of Hinkley, California.

In Estonia, where Juur grew up, she had watched “Erin Brockovich” in her middle school English class. The film stuck with her, and it resonated more when she found herself living in California, newly married, and thinking she wanted children of her own someday. She knew her home received water from the Colorado River Aqueduct. If the Cadiz project proceeded, contaminated Mojave water would also flow through that aqueduct.

“How do you avoid doing dishes or bathing in contaminated water?”

Maria Juur

Glendale, Calif.

Juur was not willing to take the chance that her family might wind up consuming hexavalent chromium.

The prospect of using bottled water for everything distressed her. It violated her belief that water should be a public good. And anyway, buying bottled water wouldn’t solve the problem entirely. “How do you avoid doing dishes or bathing in contaminated water? It’s kind of an impossibility,” she says.

These concerns prompted the Center for Food Safety to join the case, led by senior attorney Adam Keats.

The Cadiz lawsuit wasn’t bound to be an easy win for Earthjustice.

The case revolved around administrative law, which governs the behavior of government agencies. Loarie explains that the standard that agencies must meet to justify policy changes is not especially demanding.

“Basically, the agency just has to explain why it’s changing its mind,” Loarie says. “Historically, there haven’t been a lot of cases where agencies get dinged for not explaining their decision. Frankly, courts are inclined to defer to whatever explanation the agency provides.”

But as both sides prepared their legal briefs, the Trump administration started losing case after case for lack of this basic justification.

Last year, for example, a federal judge took the EPA to task for its suspension of an important clean water rule. Another court forced the EPA to implement lifesaving safety regulations for chemical plants — a victory for Earthjustice, which litigated the case.

Overall, Earthjustice has won more than 85% of the decisions in our lawsuits against the Trump administration.

On June 20, 2019, Loarie argued in federal court that, once again, the Trump administration was violating administrative law.

Less than 24 hours later, the judge issued his ruling. He agreed with Earthjustice that the Railroad Act could only be used for activities that further a railroad purpose, and that the Bureau of Land Management had failed to explain how the Cadiz project does so. The Bureau of Land Management’s actions, he concluded, were “arbitrary and capricious.”

The pipeline project was officially back to the drawing board. More good news came a few weeks later, when California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill requiring state-level environmental reviews for the Cadiz project. The company continues to say it will revise its plans and get the pipeline approved. In Loarie’s opinion, this is unlikely. Anderson worries that as climate change ravages California’s water supply, corporations will come up with more reckless water-mining proposals.

“I can’t help but think that as long as there are people out there, they’re going to continue to think of these crazy things,” she says.

For now, the desert blooms remain riotous.

Epilogue: March 2021

Ileene Anderson saw this coming.

In 2019, she surmised that we hadn’t seen the last of reckless water-mining proposals in the Mojave. Just as she predicted, Cadiz has cooked up another dubious scheme to wring water from the desert — and Trump administration officials found a last-minute opportunity to give it a hand.

Cadiz’s latest plot involves pushing billions of gallons of water through a defunct oil and gas pipeline that crosses Mojave Trails National Monument. Federal law requires the government to complete a full environmental analysis before it decides whether to grant permits to this type of project.

But in December 2020, with one foot already out the door, the Trump administration handed Cadiz an early Christmas gift when it issued the project a right-of-way with no environmental review. The administration skirted an environmental review by neglecting to consider the link between Cadiz’s water project and the pipeline — even though draining the desert’s aquifers would have a vastly different environmental impact than transporting oil and gas across the sands.

Represented by Earthjustice, conservation groups are suing the U.S. Bureau of Land Management for illegally skipping over this critical assessment. The tortoises, birds, and wildflowers of the Mojave remain just as dependent as ever on the desert’s water staying in the ground. As for us, we’ll be advocating in court until Cadiz’s ill-advised plan is derailed.

The California Regional Office fights for the rights of all to a healthy environment regardless of where in the state they live; we fight to protect the magnificent natural spaces and wildlife found in California; and we fight to transition California to a zero-emissions future where cars, trucks, buildings, and power plants run on clean energy, not fossil fuels.

Greg Loarie, a senior attorney in the California Regonal Office, joined Earthjustice in 2001. His legal docket focuses on endangered species and forestry issues in the Sierra Nevada. Rebecca Cohen tells the stories of the people and places of Earthjustice's work. Scott Womack is an illustrator and graphic designer.