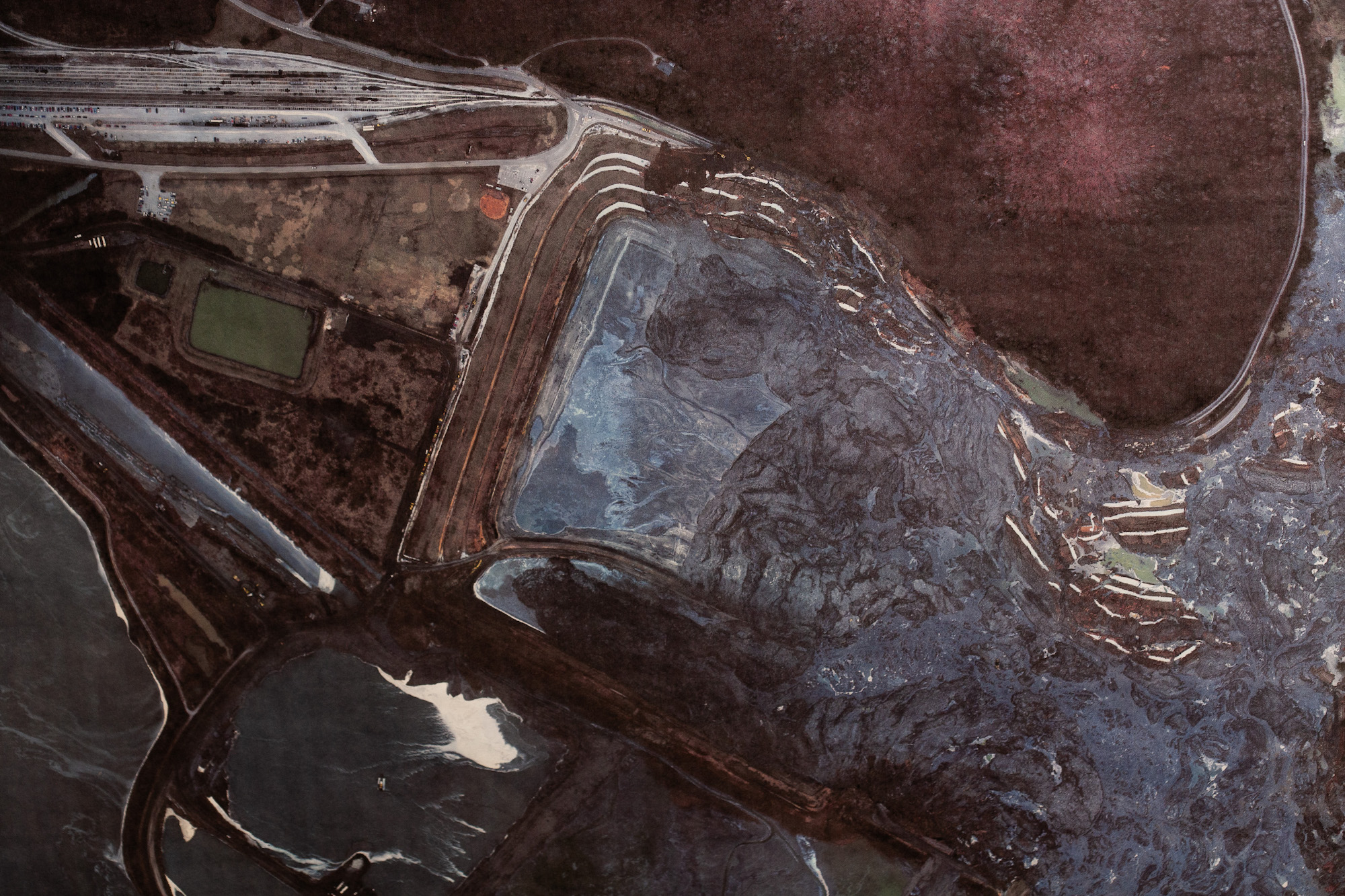

Betty Johnson calls the day 15 years ago when her husband, Tommy, a heavy machinery operator, rushed to Tennessee’s Kingston Fossil Plant “a tragedy we’ll never forget.” More than 1 billion gallons of coal ash slurry — the toxic waste left over from burning coal to generate electricity — had punched through the wall of an unlined, six-story pit about the size of Nashville’s Centennial Park.

Tommy Johnson was among scores of first responders to what remains the nation’s largest industrial disaster. The slurry crashed across the Emory River like a mudslide, shattering trees, pushing homes off of their foundations, and eventually swallowing more than 300 acres as it polluted two major waterways. The 2008 spill, with a volume five times greater than the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe, alerted people to the dangers of coal ash and forced the Tennessee Valley Authority, or TVA, which owned and operated the site, and other utilities to confront the environmental and health impacts of half a century of waste buildup. The calamity destroyed scores of homes in the tiny East Tennessee community of Swan Pond, roughly 30 minutes west of Knoxville. But for families like the Johnsons, the real tragedy came when the workers who cleaned up the mess got sick.

“When my husband went to work there, he was a 300-pound, very healthy, very active man,” Johnson recalled one day in April from a podium outside Westminster Presbyterian Church in Knoxville. Behind her, a black vinyl sign marked “Workers Memorial Day,” an international recognition of those killed or injured on the job. After the spill, Tommy developed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, low kidney function requiring dialysis, and skin lesions. He also suffered weekly fainting spells.

“His body is weak, he gets tired. He can’t even drive a car by himself because he’ll pass out,” said Johnson, who quit her job to become full-time caretaker to a man she’s known for 38 years. “We wanted to go around the country, visit, see things, but that’s not going to happen anymore. He can’t visit his grandkids because of his illness, and it’s because of the toxic coal ash.”

Since the mid-20th century, when coal became the dominant fuel to generate electricity, utilities have stored almost 5 billion tons of coal ash at more than 1,000 sites nationwide. These dumps are divided into two categories: ponds that store it in a wet slurry and landfills that store it as dry powder. Most are unlined and many are uncovered, allowing contaminants to leach into waterways or linger in the air. Today, at least 9 out of 10 coal-fired power plants are contaminating groundwater.

Coal ash contains at least 17 dangerous heavy and radioactive metals, including at least six neurotoxins and five known or suspected carcinogens, such as arsenic, chromium, mercury, lead, radium, and selenium. Prolonged exposure to coal ash can impact every major organ system, causing birth defects; heart, lung, and neurological diseases; and a variety of cancers.

Avner Vengosh, a geochemist and professor of environmental quality at Duke University, began studying coal ash when he arrived at Kingston a few days after the spill. The following May, he released a study warning that workers and residents faced grave health risks from contaminants in the ash. But people like Tommy Johnson would spend the next six years toiling without personal protective equipment like dust masks, Tyvek suits, or respirators. More than 50 have since died, and over 150 are sick, according to the Tennessee Lookout. (TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks rejected Vengosh’s findings, and even now continues to cast doubt on his methods. Vengosh, whose peer-reviewed report appeared in a top environmental science journal, called TVA’s criticisms of his work “baseless.”)

In 2015, after decades of waffling over what to do with the waste, the EPA finally issued a law regulating coal ash, largely in response to the Kingston disaster and almost 160 documented cases of water contamination from the pollutant. The rules forced utilities to monitor contamination and create cleanup plans.

“It’s unfortunate that it had to take this many years for industry to be called out to admit that numerous dump sites were contaminating groundwater, but it’s how this system works,” said Lisa Evans, senior counsel for Earthjustice. “Unless you have a specific rule requiring investigation and cleanup, industry is just not going to do it.”

But the rule covered only half of U.S. coal ash. The rest, stored in inactive legacy sites, continues polluting the environment, largely without remedy. According to a tally of industry data by Earthjustice, as many as 808 ponds and landfills, including at least one at Kingston, were exempt. (A preliminary EPA finding shows 261 sites: 134 landfills and 127 ponds.) In May, after several rounds of lawsuits, the EPA proposed an amendment to the rule that will cover most of these legacy sites.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, told Grist in an email that the 2015 order was in line with past decisions under the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, which governs the coal ash rule. But the agency said the proposed change was driven by a record showing that regulating legacy sites “will have significant public health and environmental benefits.”

The agency is expected to finalize the rule by May 6, 2024. Six months later, the new law will go into effect. While environmental advocates are hopeful, noting that closing the loophole is long overdue, they warn that the change may not entirely solve the problem. Simply including more sites in the rule doesn’t guarantee greater federal oversight, accelerate the cleanup by industry, or ensure an increase in community and environmental protection.

Betty Johnson plans to be in Chicago on June 28* for a public hearing on the amendment, where she will speak up for her husband and others who have suffered after doing their part to clean up the messes others left behind.

“I want to warn people about coal ash,” she told Grist by phone. “People don’t realize how dangerous it is.”

The stacks of the Cane Run and Mill Creek power plants loom over the banks on Kentucky’s side of the Ohio River. They go largely unnoticed by those who gather on the river, the largest tributary of the Mississippi, to paddle, or fish, or spend the day boating. Each summer, the shoreline brims with blue stands of chicory and the pink pods of swamp milkweed. The wide, flowering leaves of catalpas hang over the water, framed by tall oaks. Even in winter, when the foliage fades and falls, the area retains its beauty.

Yet those two power plants, which sit roughly 20 miles apart and are owned by Louisville Gas & Electric and Kentucky Utilities, are home to at least four of the state’s 25 unregulated coal ash sites. In 2021, a pair of studies by the University of Louisville showed that children experienced increasing health risks the closer they lived to the plants. Kids age 6-14 faced an escalating threat of neurobehavioral issues like anxiety, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and social problems. Their nail samples also contained elevated concentrations of heavy metals like chromium, manganese, and zinc, all of which are coal ash constituents.

“Once you’re exposed to coal ash, it really is a major risk to human health,” Vengosh told Grist. Over the last 15 years, his studies of water near and beneath coal ash sites, and from lakes located near regulated and unregulated sites in North Carolina, show that not only does the material leach contaminants into groundwater, but the pollutant has entered the broader environment, in some cases occurring in 50 percent of lake bed sediment. Climate events, like hurricanes, further the spread of pollution. “Closing [all the sites] is a must that should have been done eight years ago,” Vengosh said.

The fight to regulate these remaining sites began in 2016, when Earthjustice sued over a loophole that excluded ponds created by utilities that stopped generating electricity before the rule took effect in October 2015. Two years later, a federal appeals court determined these sites — also called surface impoundments — required regulation because they pose a significant threat to “human health and the environment through catastrophic failure.” The court order cited two legacy pond disasters: a 2009 pipe break at the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Widows Creek site that dumped over 6 million gallons of coal ash into local waterways and the 2014 Duke Energy spill of 27 million gallons of the slurry into North Carolina’s Dan River.

But under the Trump administration, the EPA didn’t act and instead rolled back coal ash regulations. In 2022, Earthjustice sued again to close another loophole that exempted landfill sites — also called CCR management units — that stopped receiving ash after October 17, 2015. In a settlement, the Biden administration agreed to review and revise the 2015 rule. In May, it formally proposed including most unregulated ponds and landfills in the federal coal ash rule.

The expanded regulation is necessary because “some of the most dangerous sites in our region” are those excluded from the 2015 rule, said Frank Holleman, an attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center who has fought for tighter regulation of coal ash dumps. These unlined, largely abandoned and unmonitored locations are “ticking time bombs,” he said, and most if not all of them are below the water table, threatening drinking water. “There is no distinction between regulated and unregulated sites in terms of environmental threat, or the risk of catastrophic failure,” he said. In an email to Grist, the EPA agreed that “the risks of these unregulated units are like currently regulated units.”

Almost half of Kentucky’s 43 regulated coal ash areas have a hazard risk high enough to cause environmental damage, economic losses, or loss of life, according to an analysis by the Ohio River Valley Institute, an Appalachian think tank. (Kentucky isn’t alone; for decades before the Kingston spill, the Tennessee Valley Authority ignored “red flag” warnings over the safety and stability of its coal ash ponds, according to the agency’s inspector general.) When a coal plant shutters, the towns around them — more often than not low-income and communities of color — are left to police the waste left behind.

“Unlined ponds and landfills, and the legacy of the undermanagement of waste, are part of the burden that this generation carries, and it’s important that we not pass that burden on to the next generation,” said Tom Fitzgerald, retired director of the Kentucky Resources Council, a nonprofit that provides legal representation in environmental cases. “Utilities have the ability to absorb those costs, and in some cases, it’ll be ratepayers that pay those costs. But those costs are currently being borne, off the books, by people who live in contaminated areas.”

The amendment is important because under current federal law, if a utility reports a high level or significant increase in a coal ash constituent like arsenic, lithium, or radium, it is only required to remedy the pollution if the source is a regulated site. Should the company link the contamination to an unregulated facility, it can essentially ignore the problem.

The EPA said it found power plants actively disposing of coal ash in areas outside regulated units, and 42 instances where companies managing the coal ash blamed groundwater contamination on unregulated units.

In the 2023 proposal, the EPA investigated 10 facilities across nine states that had reported high levels of contaminants but blamed the potential pollution on the unregulated coal ash sites. Examples abound: Nevada’s Reid Gardner Generating Station, neighboring the Moapa Band of Paiutes reservation, continues leaking at least 10 contaminants at levels above groundwater protection standards, including 682 times the lithium, 252 times the arsenic, and almost double the radium allowed by law. But owner-operator NV Energy blames the pollution on an unregulated pond complex dating to the 1970s and has so far avoided cleanup.

At Pennsylvania’s New Castle Generating Station, where owner GenOn Power Midwest LP self-reported arsenic at levels 372 times higher, on average, than EPA health standards, the company blamed the contamination on an unregulated landfill directly underneath its regulated landfill, again avoiding cleanup.

On a crook in the Cumberland River in southeastern Kentucky, East Kentucky Power Cooperative’s Cooper Station also manages a regulated, lined landfill directly over an unregulated, unlined coal ash pond that has collected waste since 1965. Utility reports note the site has “extremely high karst potential” — meaning the highly permeable bedrock below dissolves easily and readily transports water. Such groundwater movement may have facilitated the release of boron, calcium, and sulfate, but the owner said the regulated landfill wasn’t responsible for the pollution.

According to the EPA, these sites, and hundreds more, will be included under its revision to the 2015 rule. John Mura, executive director of communication at the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, confirmed that Cooper’s “very old former ash pond” will be brought “into the fold with this new rule.”

Abel Russ, an attorney with the Environmental Integrity Project, said the proposed rule makes sense from a cleanup perspective because it allows utilities to deal with all of the ash rather than picking and choosing which sites to clean and close and which to blame for continued contamination. Another benefit: The 2021 study by the Ohio River Valley Institute argues that a “clean closure” plan could create hundreds of jobs at coal plants and bring money to local economies.

“It will make cleanup more efficient, more effective, and more logical, which should be to everyone’s benefit, even owners,” said Russ.

While most environmental advocates say they’re happy with the proposal, they note several very specific exemptions that apply to perhaps 50 sites. For example, active power plants that claim not to have regulated units, or long-closed power plants that claim not to have legacy ponds, are exempt. The EPA said it is soliciting comments, “but currently, the Agency lacks sufficient data to support regulating these units.”

“That’s a gap we want EPA to close, because old landfills at retired plants are likely to be leaking hazardous contaminants just like all other landfills. There’s no difference and no less risk,” said Evans. “We don’t think it’s a huge number of sites, but there’s no reason to exclude them.”

John Ward, communications coordinator of the American Coal Ash Association, which advocates for recycling coal ash waste, said the EPA also could promote the beneficial reuse of the material instead of “just moving the ash from one disposal site to another.” Encapsulated ash used in cement and concrete could help decarbonize those industries, but Ward said it would require more flexible timelines and compliance.

“In all of these EPA regulations the compliance guidelines are generally very tight,” said Ward. “The [EPA] would probably have to allow a different timeline for cases where an owner-operator will go to the expense of setting up a harvesting operation and the time it takes for markets to absorb those materials.”

The EPA says the rule doesn’t change beneficial use requirements and it “did not propose to change the closure completion timeframes for the newly regulated units.”

But perhaps the biggest critique is EPA’s continued lack of enforcement, even after it proposed making the coal ash rule an enforcement priority for 2024. EPA said its enforcement program ensures landfills and ponds “do not present dangerous structural stability issues (such as those that led to the catastrophic 2008 Kingston Tennessee coal ash disaster) that could put surrounding communities in harm’s way,” while monitoring groundwater data, cleanup, and closure “to determine whether facilities are complying with the regulatory requirements and adequately addressing coal ash disposal risks.”

But according to a 2022 study, seven years after the initial ruling, only 4 percent of utilities have selected a cleanup plan for contaminated groundwater. Only two citizen enforcement lawsuits, both in litigation, have been brought. No state has brought an enforcement action under the rule. EPA said it cannot comment on specific ongoing matters.

Evans said it’s unlikely the proposal will spur any new EPA enforcement. What it could provide are “more opportunities for enforcement by the EPA, citizens, and states,” she said. “Certain things make it more easily enforceable like clear language and compliance documentation that’s publicly available and transparent.” But, she added, “There’s no substitute for a strong presence by the EPA to ensure that the utilities are complying with the law.”

When workers like Tommy Johnson began cleaning up the Kingston spill, they piled some of the coal ash on top of a pond that Amanda Garcia, attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center, calls the ballfield. While TVA has so far called the site an inactive, and therefore unregulated, landfill, Garcia said the 2023 proposal will require it to clean up that site.

“Even after the Kingston spill, TVA has been dragging their feet,” said Garcia. “Putting more power in the hands of directly affected communities is a really important outcome of this rulemaking.”

The TVA’s Scott Brooks did not respond to specific questions about its coal ash sites, but he said the agency is “reviewing the proposed federal rule and how it will apply to our program” and that it wouldn’t impact “our steadfast commitment and efforts to safe, innovative, responsible coal ash management.”

In 2013, Tommy Johnson joined more than 200 others in suing TVA’s cleanup contractor, Jacobs, alleging the health conditions they suffered stemmed from their coal ash exposure. In 2018, a Knoxville jury ruled that their illnesses were linked to coal ash, but a second phase of the trial that could have brought individual relief and medical compensation never happened after the case went into court-ordered mediation.

This spring, after two rounds of mediation and efforts by Jacobs to slow the case, the parties reached a settlement. Workers cannot discuss it, but Janie Clark, wife of Tommy Johnson’s best friend Ansol Clark, a fellow Kingston first responder who died in May 2021 of a rare blood cancer, said, “As a widow, I’m glad for the survivors that are living, but for the families that have lost their loved ones, it’s got a hollow ring to it. It’s too little too late.”

Tommy Johnson, who was 71, never saw the end to the decadelong litigation. The day after the memorial service in which his wife so eloquently shared his struggles, he collapsed during a Sunday service at the church where he served as deacon. Three weeks later, he died.

*Correction: This story originally misstated the date of the public hearing in Chicago.

Editor’s note: Earthjustice is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.