Her Family Moved to Escape This Deadly Chemical — But It Followed

Lawmakers are trying to overturn a ban on trichloroethylene, a widely-used solvent linked to cancer and Parkinson’s disease. Here’s what it is, and one family's story after being exposed.

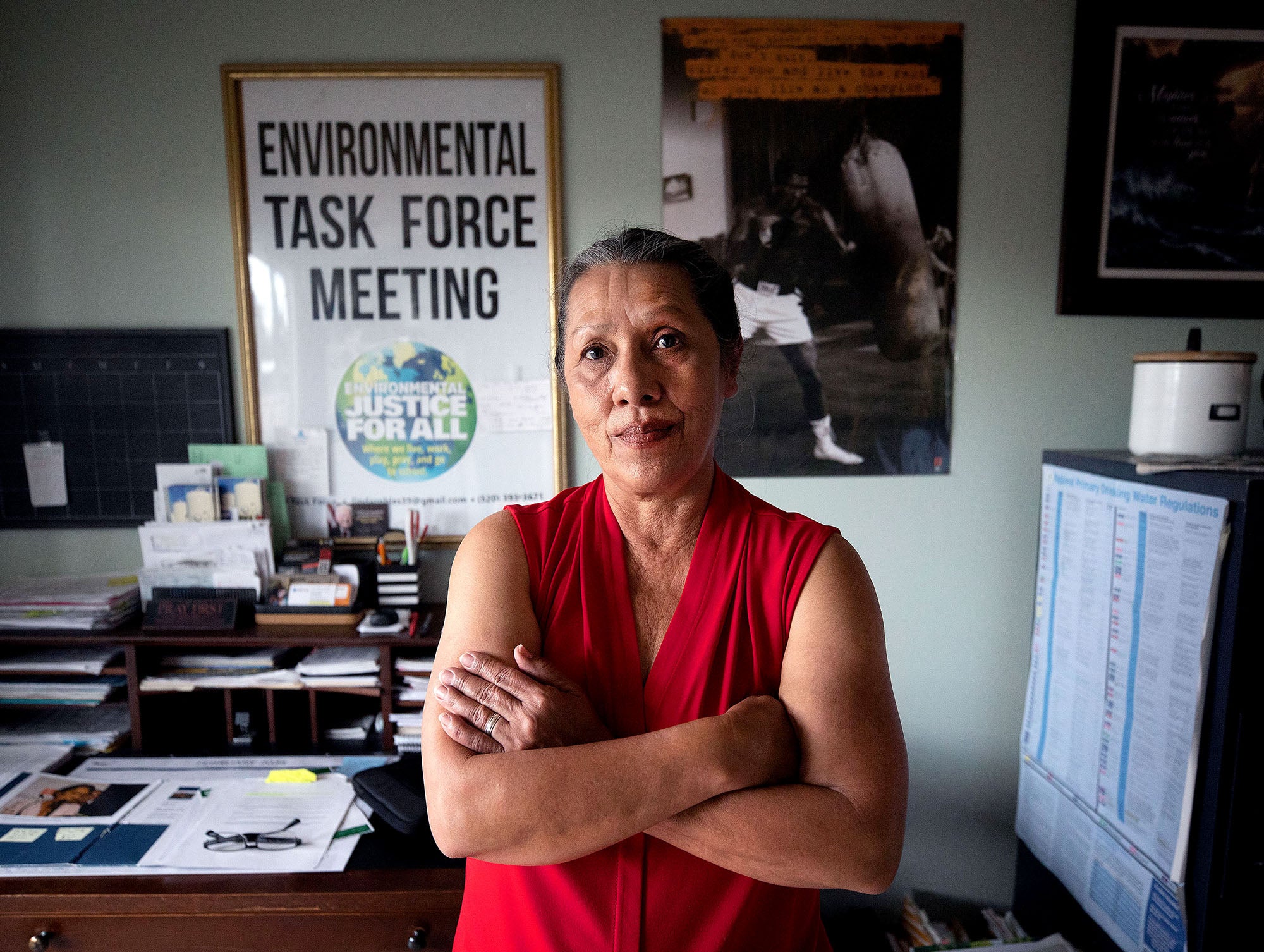

For Linda Robles, a new house was supposed to be an escape from the poison in her hometown.

She had fled the toxic groundwater discovered in southern Tucson, where a military base had spent decades dumping toxic chemicals into the ground. Among those was trichloroethylene, or TCE, a cancer-causing chemical widely used in factories, airports, and military bases to degrease metal parts. The wastewater mingled with the groundwater, turning the area’s drinking water into a deadly hazard.

After learning of the contamination, Linda Robles and her husband moved a few miles south into a newly built house to try to protect their growing family. But the toxic underground plume extended into their new neighborhood – and would soon take its toll on their young family.

“I tried to run away from the TCE,” recalls Robles. “It followed us. Wherever water goes, those chemicals follow.”

The Biden administration banned most uses of TCE in December 2024 – but now, lawmakers are trying to overturn that decision. Any delay in finally getting rid of TCE in our communities leaves thousands of workers and families exposed to deadly, avoidable risks. We are urging members of Congress to stop attacks on this lifesaving ban.

What is trichloroethylene (TCE) and how are people exposed?

TCE is a solvent linked to severe health impacts and cancer clusters across the country. Exposure to TCE can increase the risk of leukemia, breast cancer, kidney and immune disruptions, and congenital heart defects in developing fetuses.

Though contaminated drinking water is a primary route of exposure, it’s not the only one. Because TCE can also become airborne — even when underground — it rises through contaminated soil into people’s homes in a process called vapor intrusion .

TCE can wreak havoc on entire families before someone discovers a link.

Shortly after Robles moved to Midvale in South Tucson, her daughter became extremely ill. Doctors diagnosed her with a rare form of kidney cancer. Despite all their treatments, she died within three years.

Robles’ other daughter and son soon began developing inexplicable rashes and were also diagnosed with lupus. Years later, her surviving daughter gave birth to a child with a cleft lip, who was also diagnosed with kidney disease. As rare and severe health issues spread through her family, Robles remembered the reports about TCE-linked illnesses in the hometown she’d left behind. She began having her children regularly monitored for brain and immune issues.

“I thought that since the house was newly built, we’d be away from the plumes,” Robles remembers. “But when I asked my daughter’s doctor if TCE could be the reason for her disease, he said ‘It very much could be. Let’s test all your kids.’”

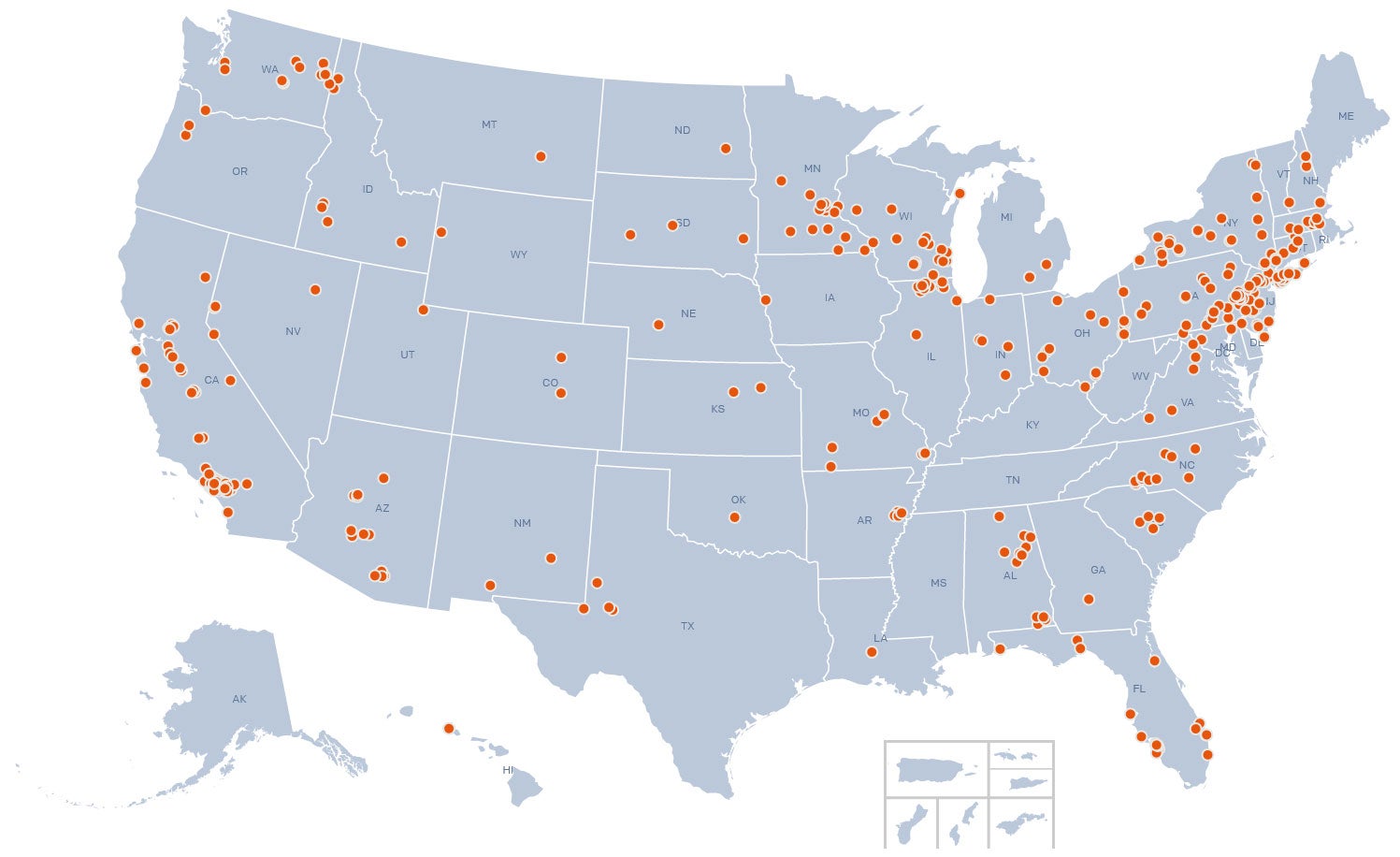

Trichloroethylene contamination has been found in the drinking water of hundreds of public water systems across the United States. See EWG’s interactive map. (Data: Environmental Working Group’s Tap Water Database / www.ewg.org)

What happens after TCE is detected in an area?

Despite the deadly harms of TCE, site remediation rarely happens quickly, if at all, due to industry pushback. Cities get dragged into multiyear fights with polluting companies and developers over who will foot the bill.

In some cases, the EPA may designate the area over a plume a Superfund site — but this doesn’t necessarily result in clean drinking water.

After the government declared Robles’ hometown a Superfund site, the city built a wastewater treatment system. Yet rather than remediate the source of the TCE plume, officials simply mixed clean water from another area with the toxic groundwater. People still drank water laced with TCE, just at an EPA-acceptable level.

Fed up with the city’s response in South Tuscon, Robles helped found Environmental Justice Task Force with other locals. They began knocking on doors to alert their neighbors about the poison in their faucets — and found that many already suspected it.

“It only took a minute before residents would list health problems in their friends and families,” says Robles. “We’re all sharing a history of the aftermath of the TCE contamination.”

Midvale is a predominantly Latino, Spanish-speaking community. Their drinking water is a toxic cocktail of TCE, dioxin, and PFAS, known as forever chemicals. The disproportionate presence of these chemicals in their community is not lost on locals, says Robles, who has since moved from Midvale.

“We were forced to drink, cook, and bathe in that water [before the city notified us],” she says. “Our properties, our health has been destroyed. The effects have been downplayed, denied, and ignored because of environmental racism.”

How has the government responded?

In 2023, Earthjustice sued the EPA over the chemical’s continued use. In response to our lawsuit, the Biden administration announced a new proposal that would phase out all existing uses of TCE, and finalized a ban in December 2024. Yet with the incoming Trump administration, industry-friendly lawmakers are now seeking to overturn that ban through a congressional review, leaving vulnerable communities at risk once more.

“When the military decided to put their hazardous waste sites in communities of color, they chose who lives or dies, whose children get sick,” says Robles. “To make that decision, to be that heartless — that’s its own health condition.”

Originally published on December 9, 2024. Updated with news of the congressional attacks on the TCE ban.

Earthjustice’s Toxic Exposure & Health Program uses the power of the law to ensure that all people have safe workplaces, neighborhoods, and schools; have access to safe drinking water and food; live in homes that are free of hazardous chemicals; and have access to safe products.