October 9, 2025

Defending the Grizzly Bear

Earthjustice stands ready to take legal action to defend the grizzly bear and ensure its continued recovery.

While federal protections afforded by the Endangered Species Act have helped foster a slow comeback of the bears in the U.S. Northern Rockies, mounting human-caused threats imperil any lasting recovery.

Once again, 2025 is trending to be a very deadly year for grizzlies, after more than 80 grizzlies were killed in 2024.

The iconic Grizzly 399 — above, with three of her cubs in Grand Teton National Park in 2013 — was killed in a vehicle strike on Oct. 22, 2024. Read an op-ed on the anniversary of her death: “Collectively, we can honor 399’s legacy by recommitting to the protections that made her life possible.” (Photo courtesy of Tom Mangelsen)

Only a handful of those deaths were attributed to natural causes. The rest were killed during surprise encounters with hunters or were exterminated over encounters with livestock or after rummaging through unsecured household trash. Others were hit by cars or trains. Some were electrocuted. A mother bear and two cubs drowned in a concrete drainage ditch. Still more were killed at the hands of poachers.

Over 95% of the grizzly deaths last year were attributable to human causes.

What’s Threatening Grizzly Bears

1. Isolation

Grizzly bear populations are vulnerable due to genetic and geographical isolation and small ‘island’ populations. This makes them more susceptible to population declines.

Solution:

Science-based management supporting natural connectivity and establishing interconnected populations of grizzly bears will increase genetic and demographic resilience.

2. Lethal State Policies

In the past decade, states in the U.S. Northern Rockies have adopted regressive anti-predator laws that are undoing wildlife recovery success stories.

Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana politicians have passed deadly policies aimed at reducing wolves. Those include wolf hunting methods as well as trapping and neck snaring practices that harm many other wildlife species, even on public lands.

Solution:

The states must change course and adopt measures that reduce grizzly mortality risk and foster grizzly recovery.

3. Human Encounters

Human developments and increased recreation are pushing grizzlies out of their habitat.

Livestock conflicts, bear-hunter encounters, and vehicle collisions are among the leading direct causes of grizzly bear deaths.

Solution:

Better management practices such as assisting livestock producers with ways to avoid grizzly encounters, along with public outreach about bear safety when hunting and recreation are vital to reducing these outcomes.

4. Habitat Fragmentation

Human development including roads, logging, mining, and urbanization degrades and fragments grizzly bear habitats.

Solution:

Wildlife connectivity areas and careful management and habitat restoration on public lands are essential to counteract these effects and support population survival.

5. A Changing Climate

A rapidly heating environment has disrupted food distribution and availability for grizzly bears, sometimes forcing them to seek other sources for calories. Climate change impacts grizzly habitats and forces grizzlies to seek food in places where they face higher risks of human conflict.

Solution:

Incorporating the best-available science into grizzly recovery that includes assessing and addressing the impacts of a warming planet on grizzlies and their habitat is essential to their long-term recovery.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering a rule that would reduce grizzly bears’ protected range and allow for more killing of the species.

The Trump administration and its allies in Congress may also attempt to fully delist the grizzly bear, which would jeopardize the recovery of the species in the lower-48 states. Delisting the grizzly bear would turn management of the species over to states with regressive anti-carnivore policies that want them trophy hunted and killed.

“They can have one or the other, but not both.”

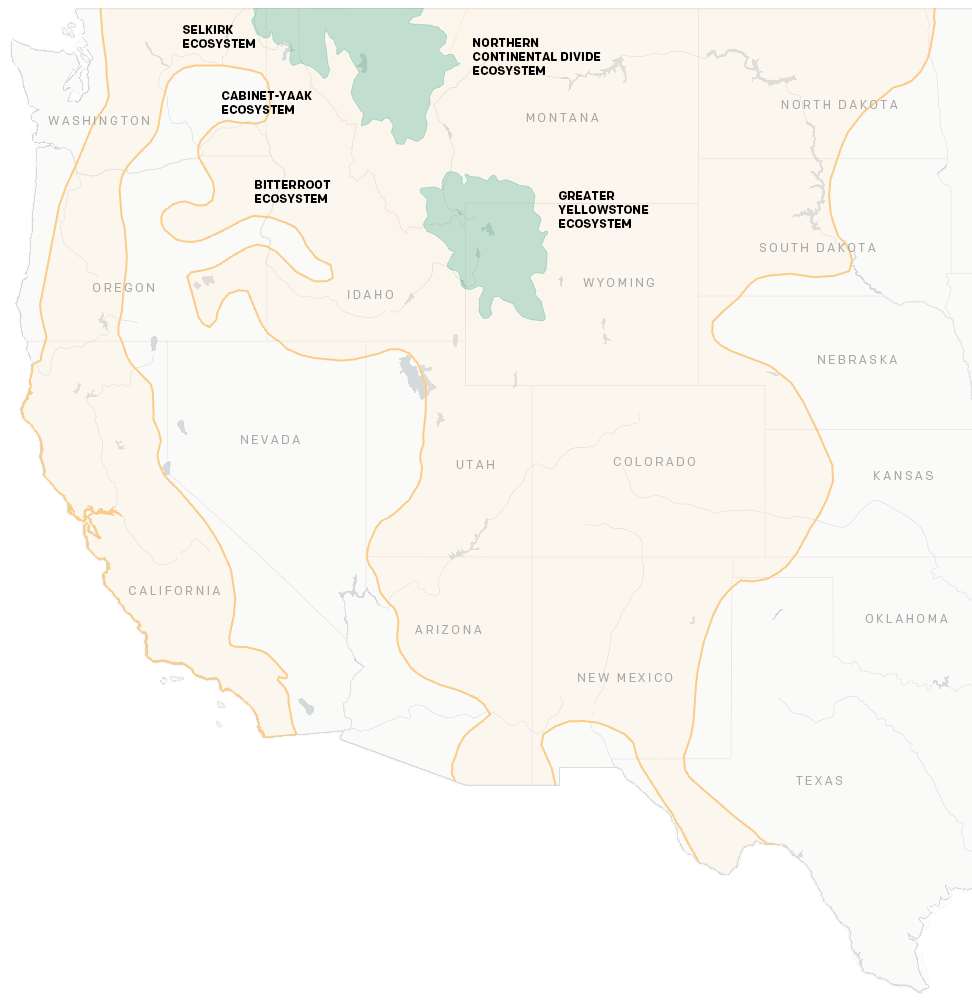

Last year, Earthjustice and 15 partner groups petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to update its grizzly recovery plan to bridge isolated populations in their former Northern Rockies range.

Citing research from Dr. Chris Servheen, former U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service grizzly bear recovery coordinator, our petition urged the agency to foster natural connectivity between isolated populations of bears.

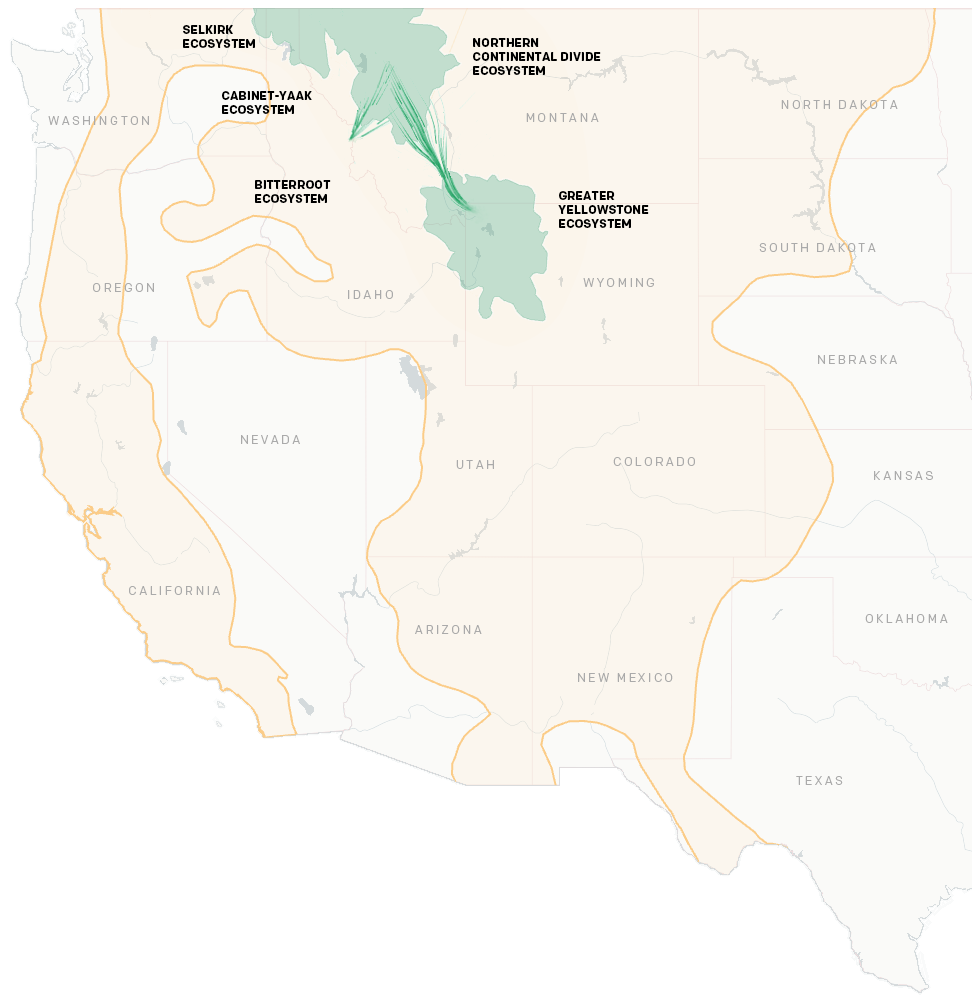

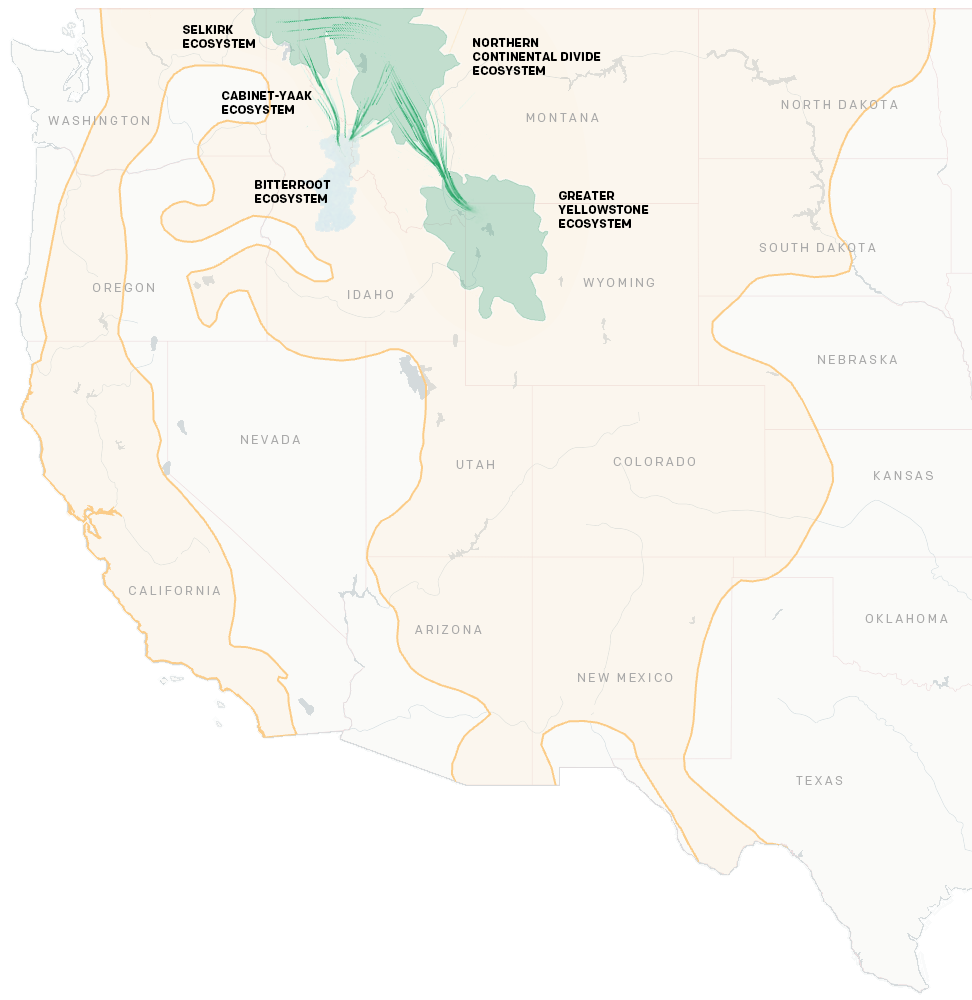

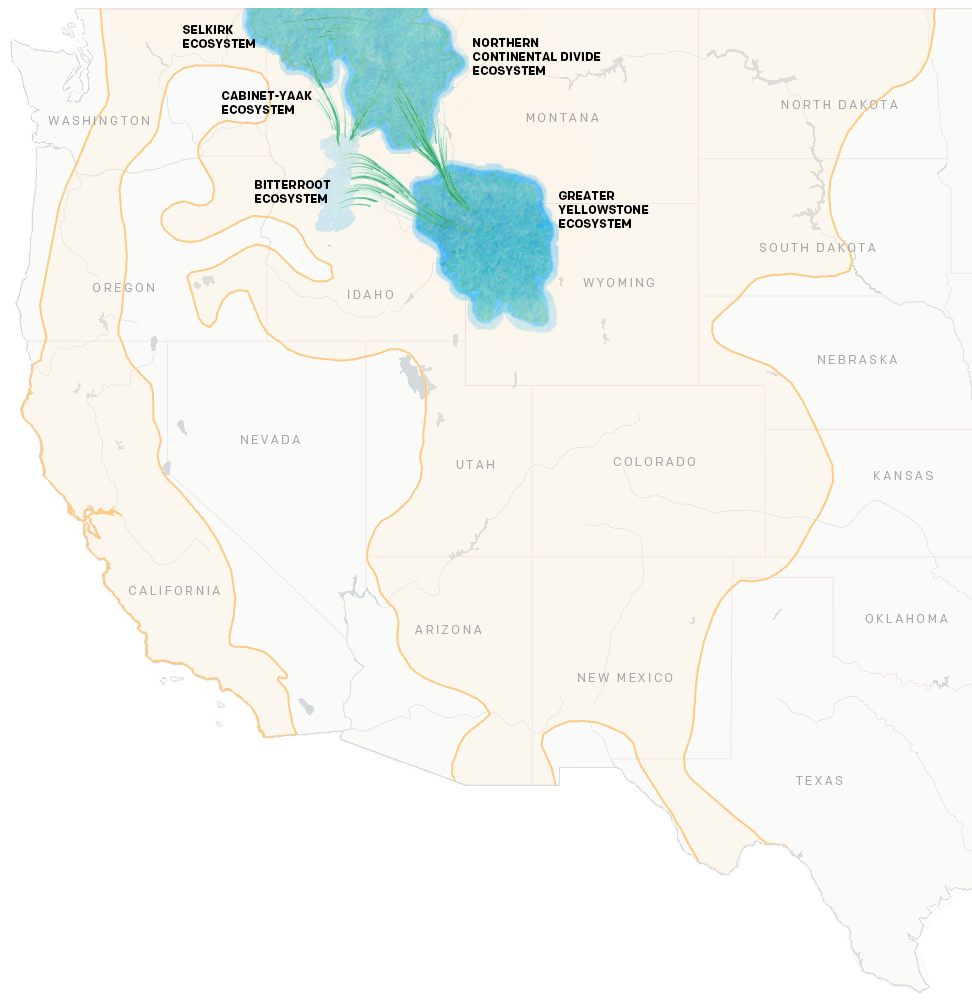

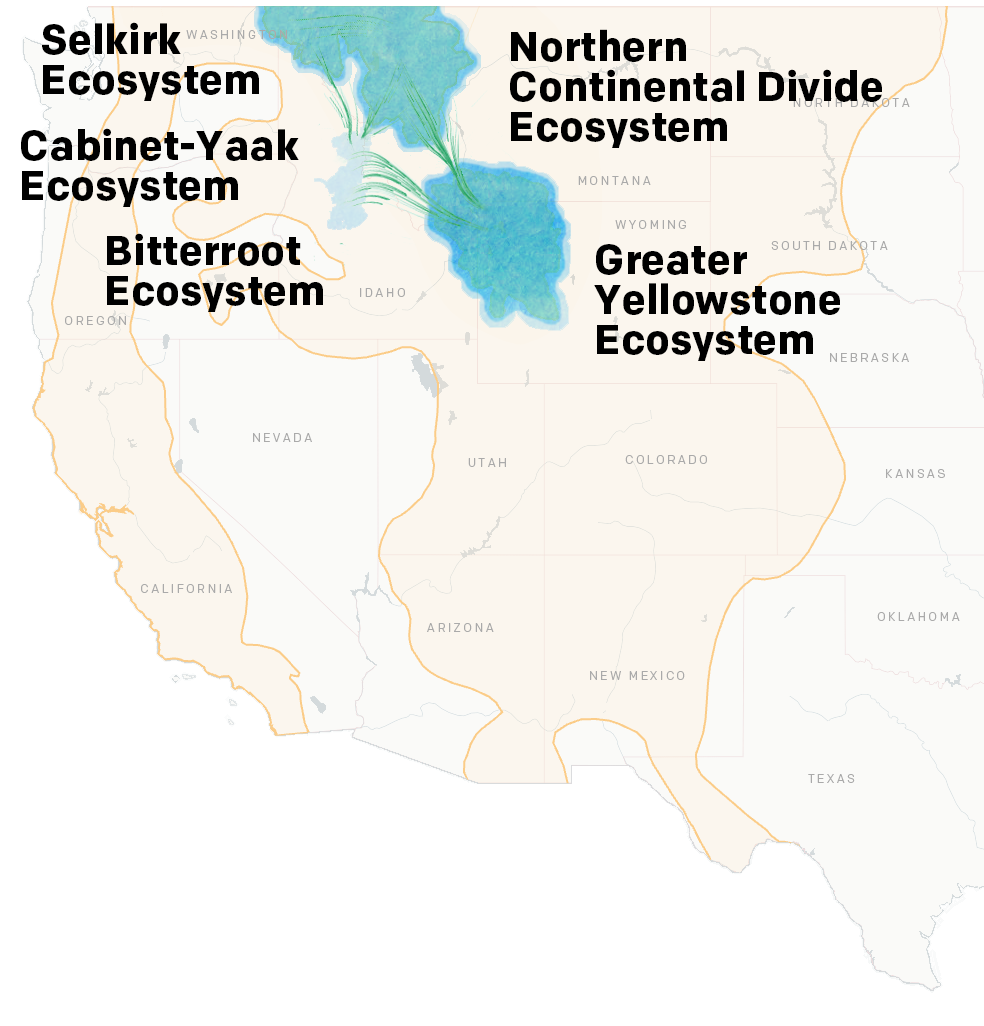

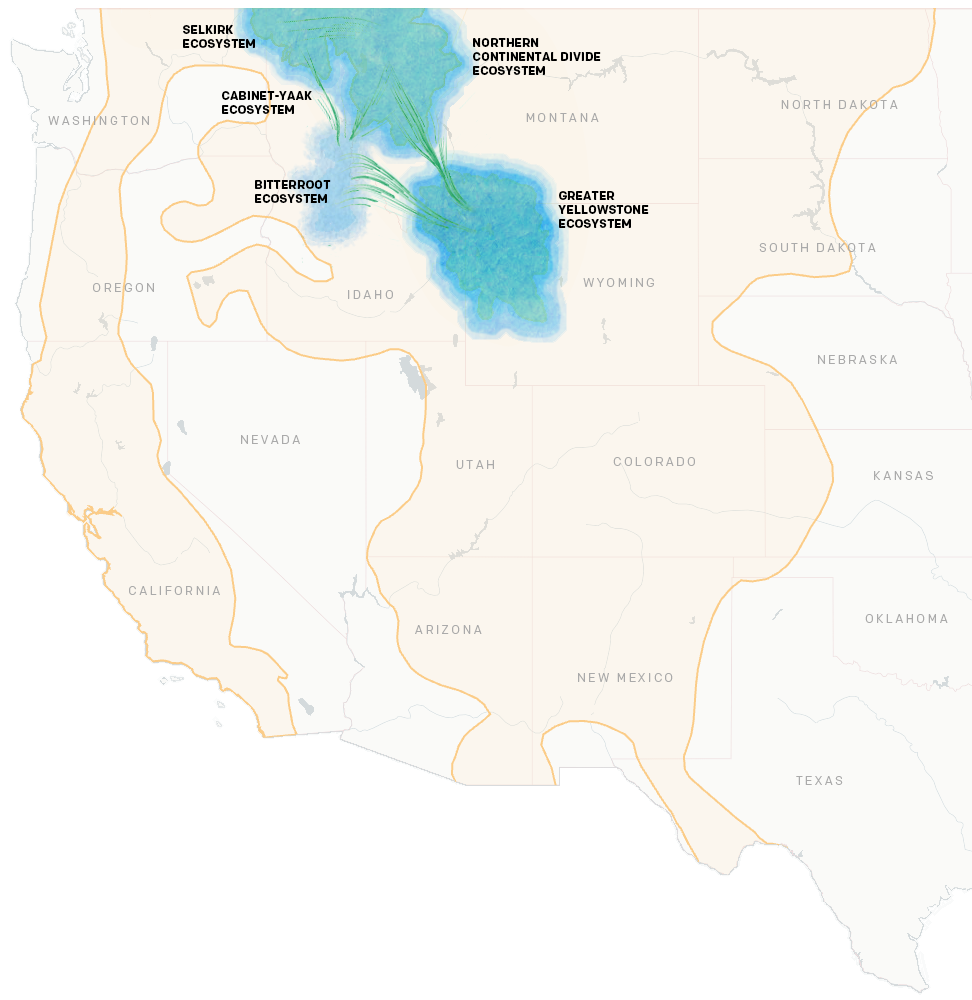

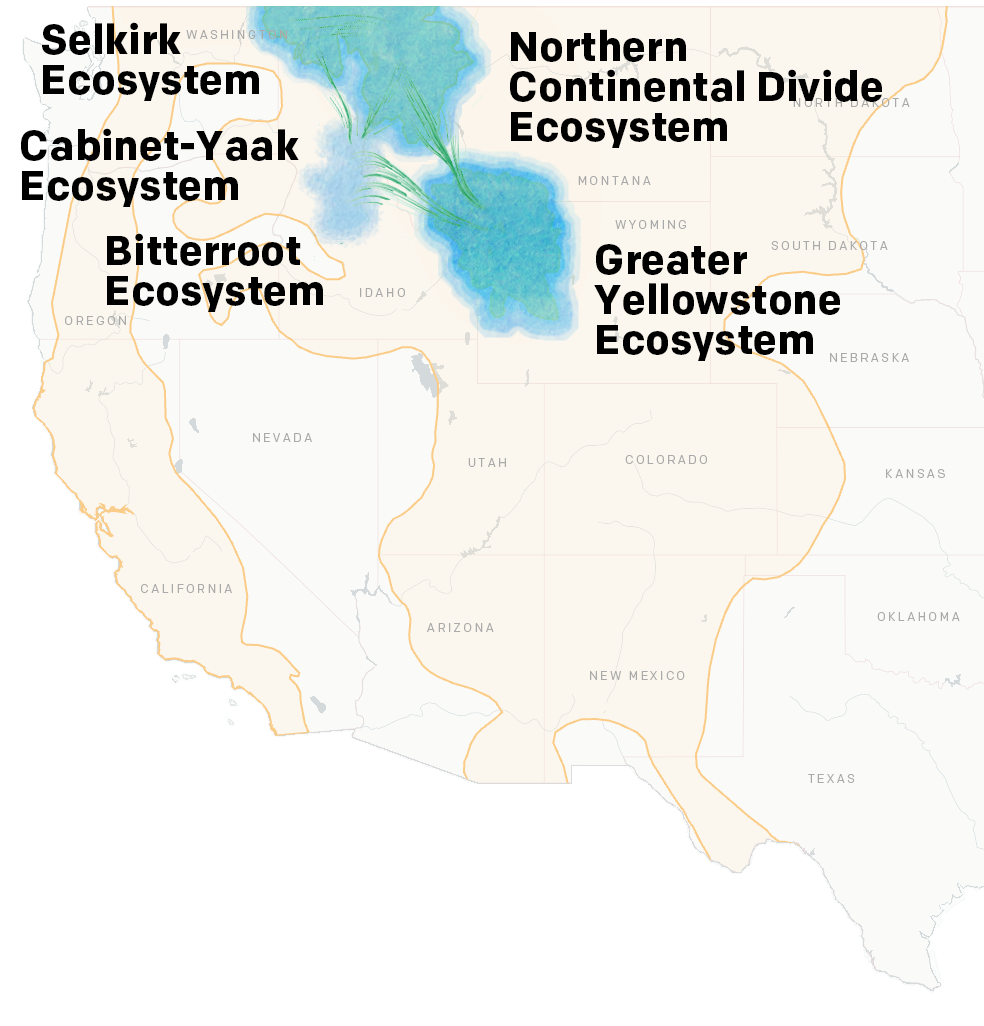

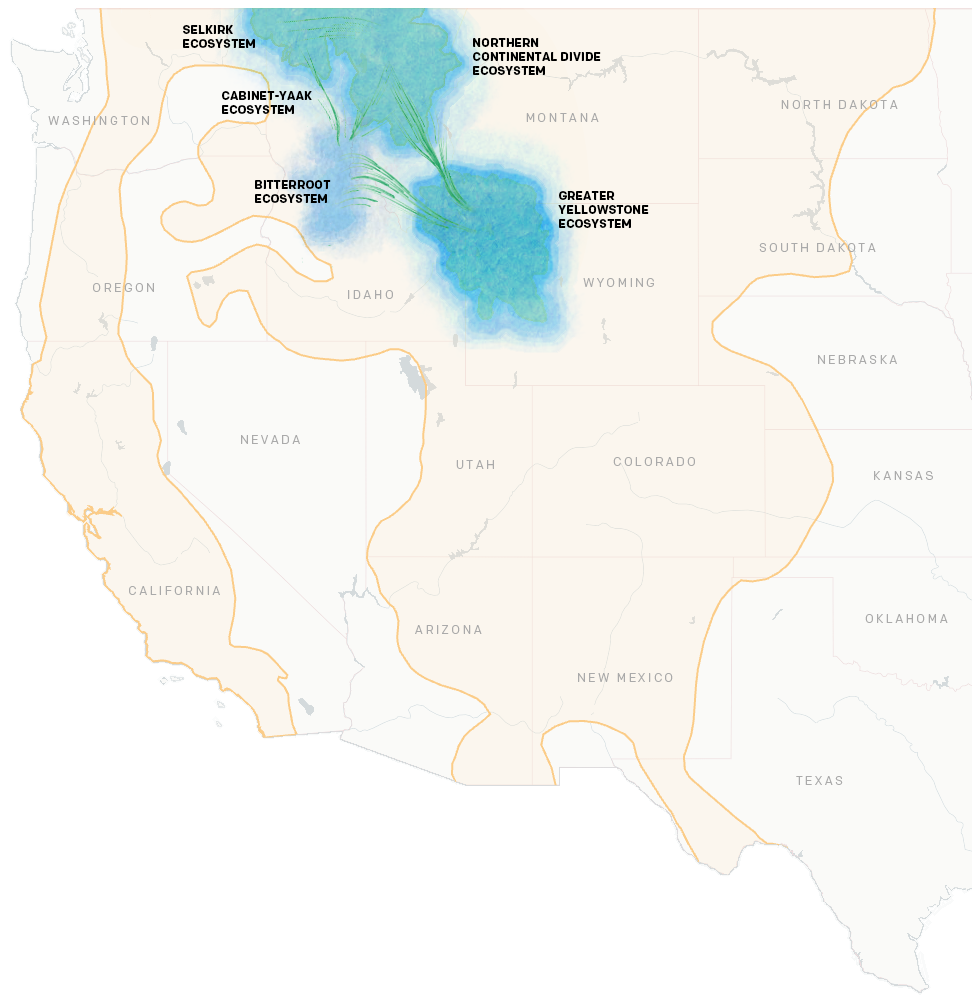

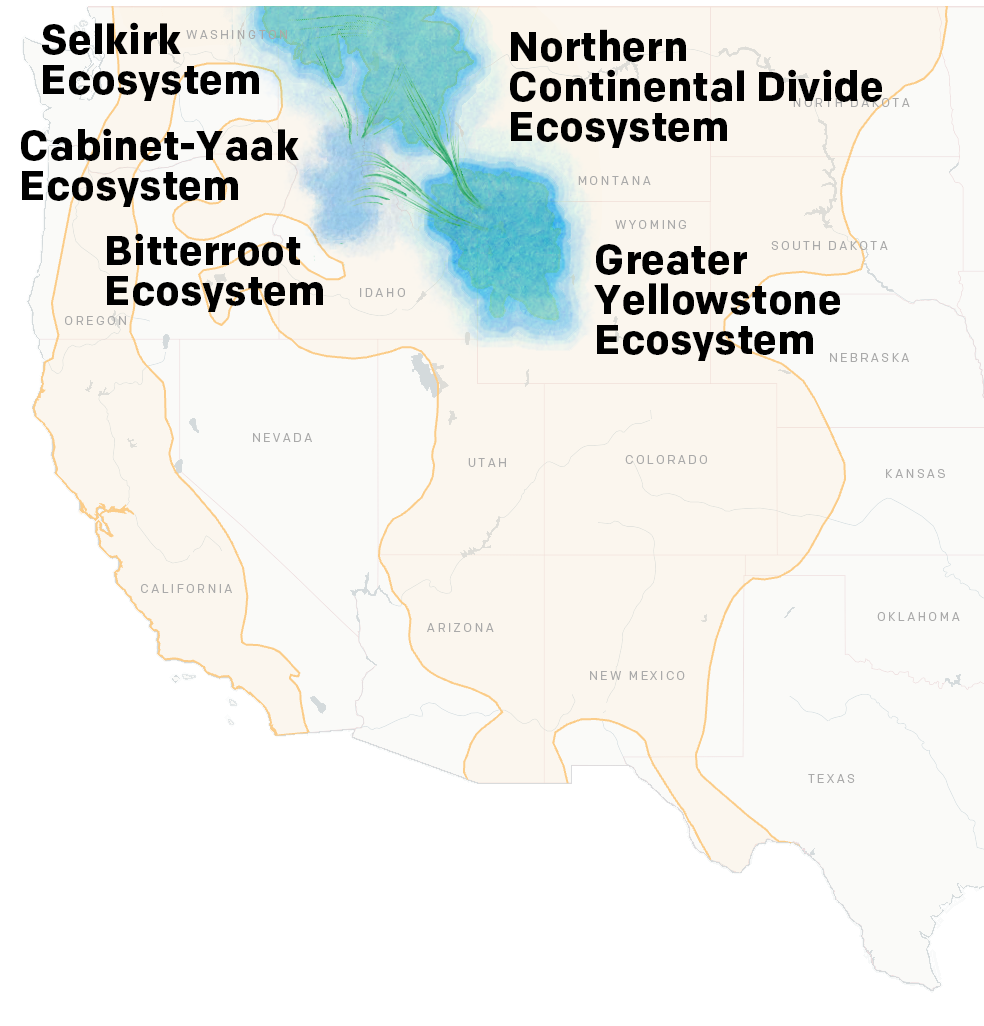

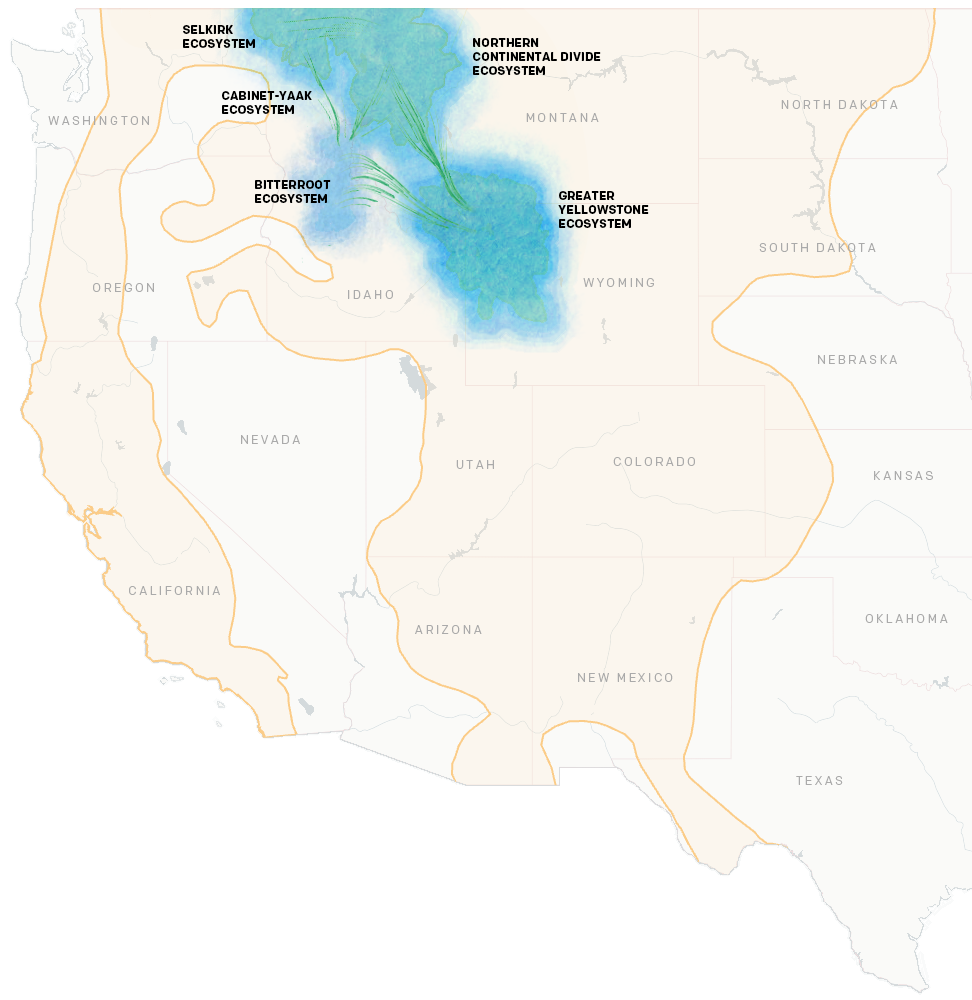

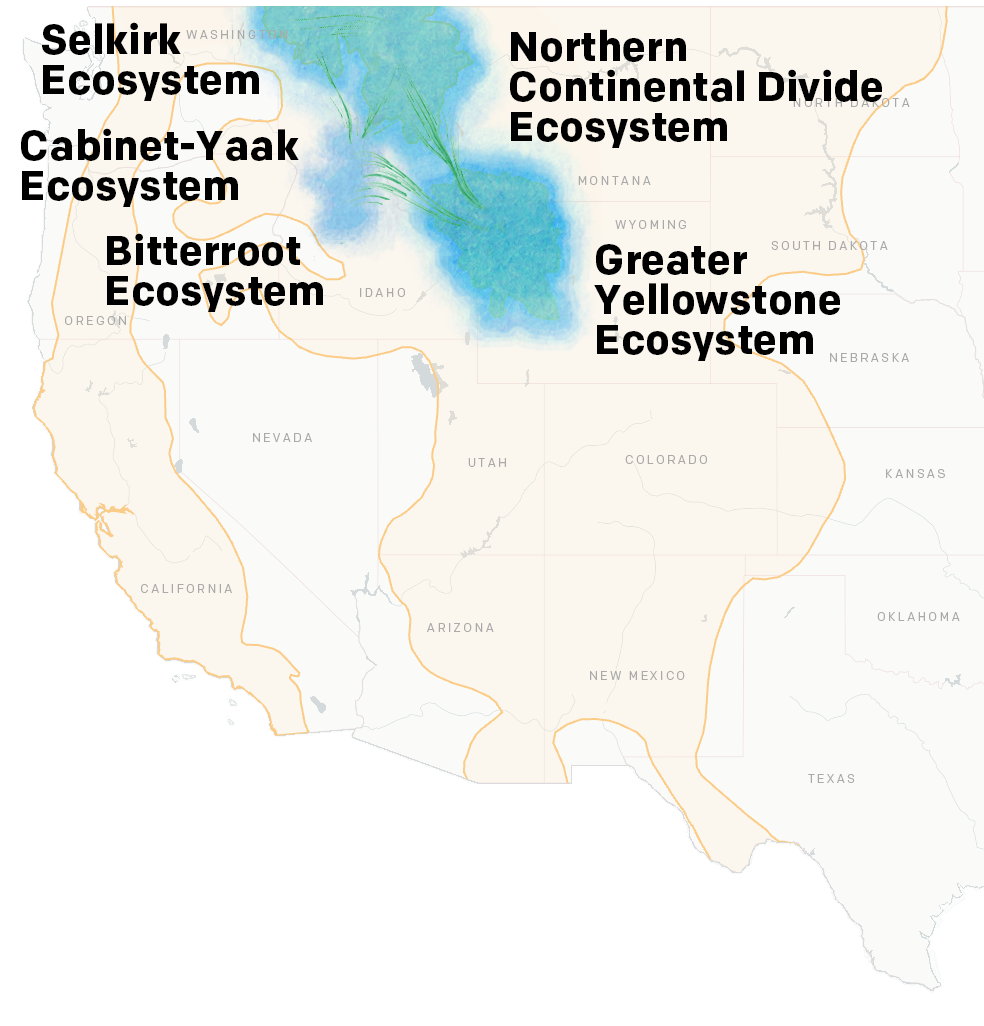

Currently, the service manages grizzlies in five isolated ecosystems: the Greater Yellowstone, the Northern Continental Divide, the Selkirk, the Cabinet-Yaak, and the Bitterroot, the last of which has no resident population of grizzlies.

Until we achieve a robust interconnected population and states commit to maintaining their recovery, grizzly bears must remain protected under the Endangered Species Act.

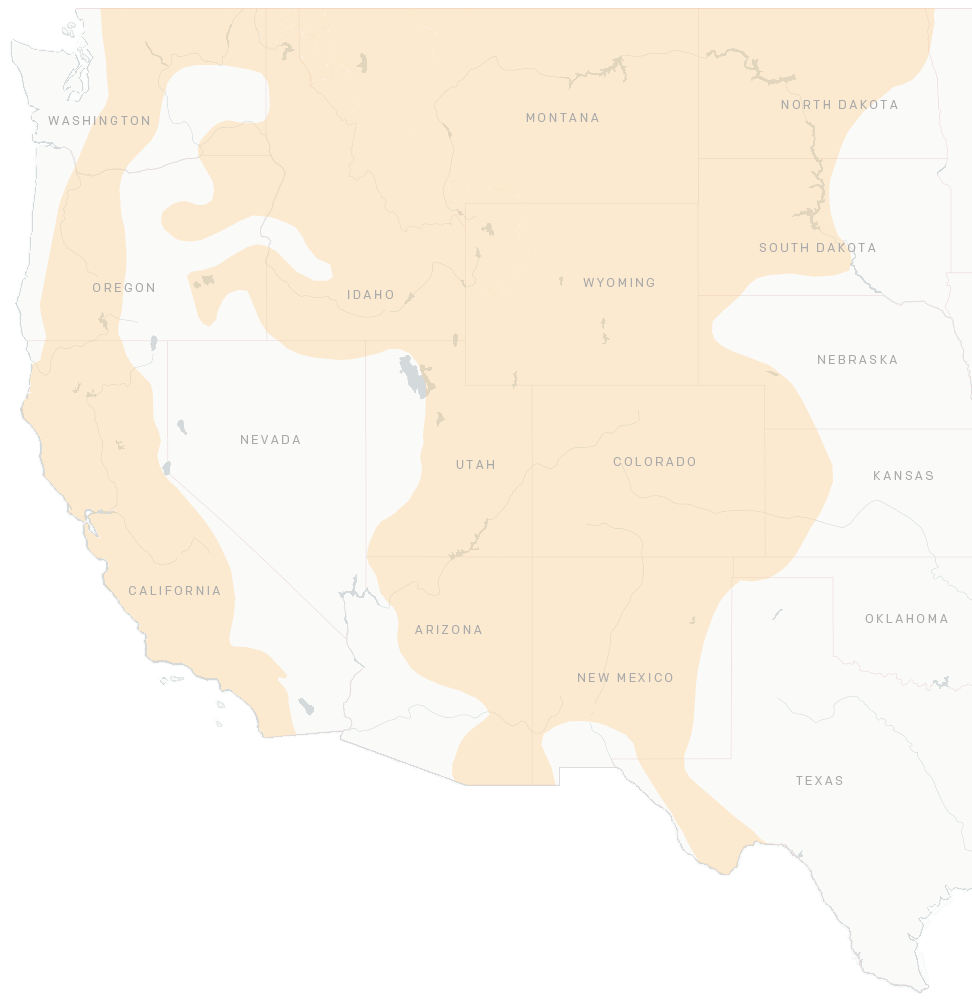

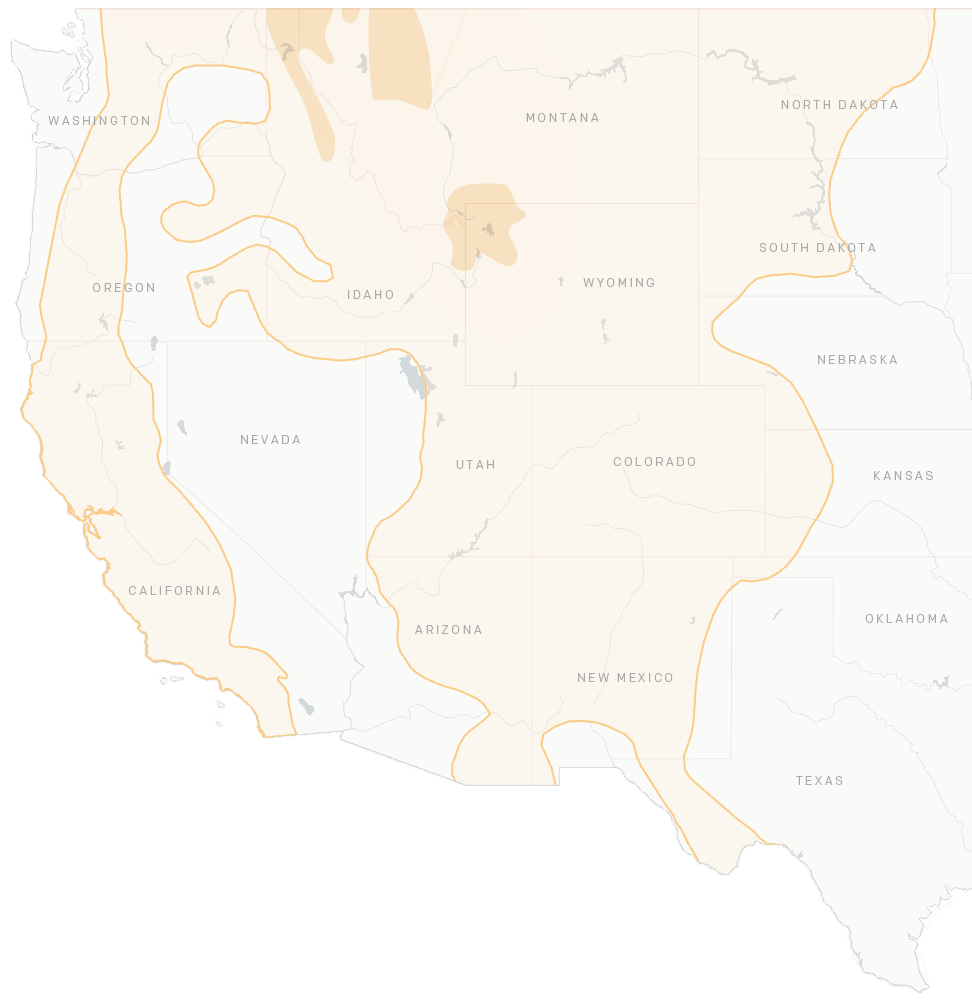

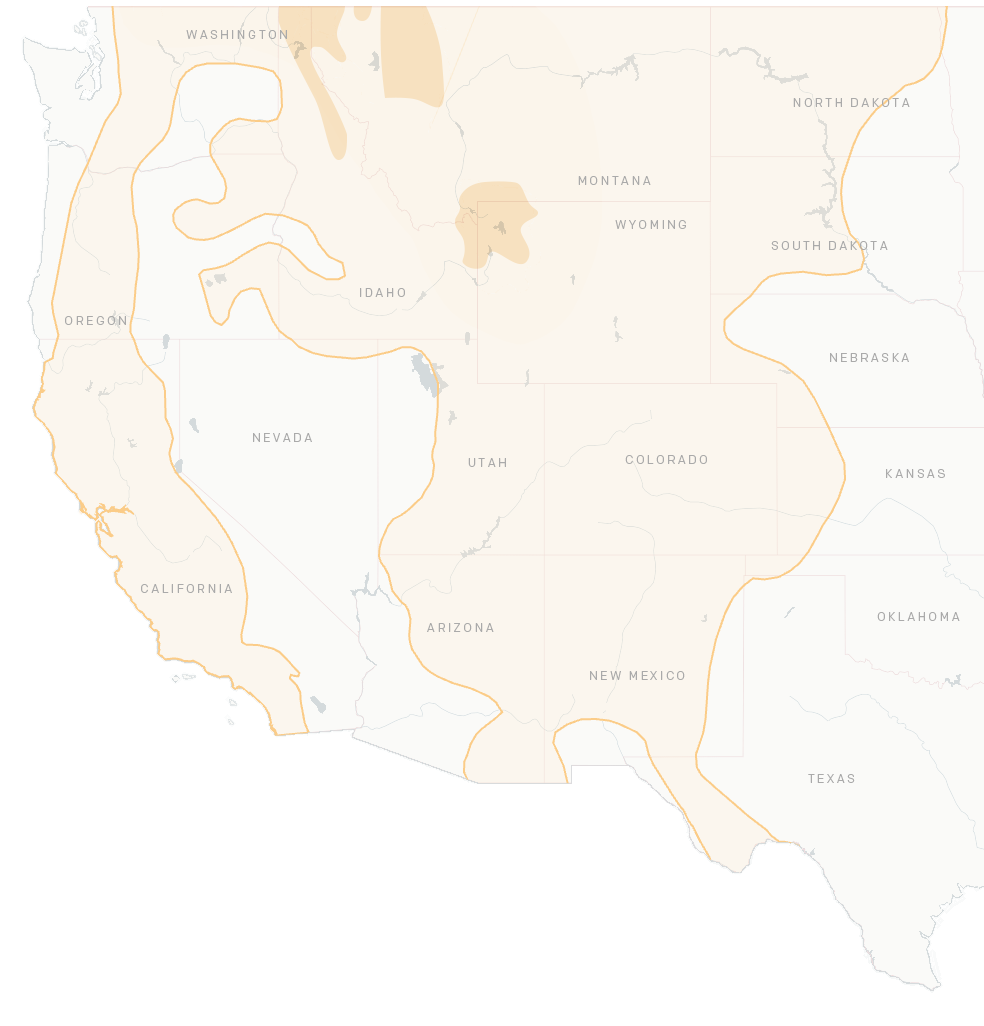

Grizzly Bear Populations in the U.S. Lower-48

Historical range of grizzlies

Estimated occupied grizzly range in 1975 when granted ESA protections

Current estimated occupied grizzly range

Potential connectivity between grizzly populations

Potential grizzly range with revised recovery plan

To live in Grizzly Country is a gift, but one that requires care and commitment to preserve it.

Unfortunately, elected officials across the region have instead displayed an anti-carnivore hysteria that puts the grizzly bear and the Northern Rockies way of life at risk.

We must demand that our elected officials assure a future for grizzly bears for generations to come — not to continue our unceasing march of development relegating grizzlies to tiny zoo populations.

Your voice is needed to defend the iconic grizzly bear. Urge the Department of Interior to consider the latest science and conservation practices to ensure grizzly bear recovery.

Photo Credits: Mist rises from grizzly's warm breath (Jim Peaco / NPS). Grizzly watches gray wolf (Kimberly Shields / NPS). Grizzly bear crossing road in Hayden Valley (Eric Johnston / NPS). Grizzly near Swan Lake (Neal Herbert / NPS). Grizzly sow and cubs near Roaring Mountain (Eric Johnston / NPS). Grizzly near Wapiti Lake (Eric Johnston / NPS).

Grizzly Mortality Data: Inset slideshow data sourced from Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team’s record of grizzly bear mortality in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem in 2024. Additionally, known grizzly mortalities in Montana can be found on the Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks website and grizzly mortalities in the Selkirk and Cabinet-Yaak on the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s website.

Map Data: Historical grizzly bear range (IUCN). 1975 grizzly bear range (National Academy of Sciences). Current occupied grizzly bear range (U.S. FWS ECOS). Grizzly bear recovery zones (U.S. FWS). Basemap © CARTO / © OpenStreetMap.

Established in 1993, Earthjustice's Northern Rockies Office, located in Bozeman, Mont., protects the region's irreplaceable natural resources by safeguarding sensitive wildlife species and their habitats and challenging harmful coal and industrial gas developments.