Columbia Basin Salmon in Peril

Wild fish populations in the Columbia Basin are in serious trouble, with key stocks teetering on the brink of extinction.

Graphics by Casey Chin

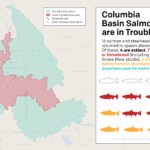

The Columbia River Basin, spanning seven U.S. states and one Canadian province, was once one of the largest salmon-producing river basins in the world.

Columbia Basin salmon are central to an entire ecosystem, providing food for a multitude of species from endangered orca whales to bears and bald eagles.

They are also critically important to sustain Northwest commercial and recreational fisheries, which provide family wage jobs from California to Alaska. And they are central to the treaty rights and ways of life of Native American Tribes, who reserved the right to continue to fish as they had traditionally when ceding millions of acres of land in the Basin.

But now many of the basin’s iconic salmon populations are hovering on the brink of extinction — and we’re running out of time to save them.

This sockeye salmon was released in Redfish Lake, Idaho, as part of a captive broodstock program to help prevent extinction. Neil Ever Osborne / Save Our Wild Salmon / iLCP

From top left, clockwise: A sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) in Little Redfish Lake Creek, Idaho. East fork of the Salmon River, one of the major tributaries of the Snake River. Chinook salmon jumping at Dagger Falls. The serpentine Bear Valley Creek. Neil Ever Osborne / Save Our Wild Salmon / iLCP

The Northwest had a plan — but now we’re back in court

In December 2023, four lower Columbia Basin tribes, the states of Oregon and Washington, and the federal government all agreed on a comprehensive plan to guide the recovery of imperiled Columbia Basin fisheries — while also investing in affordable, reliable clean energy and planning for removal of four lethal federal dams on the lower Snake River.

Unfortunately, in June 2025, the Trump administration reneged on that agreement in favor of his previous administration’s illegal 2020 plan that ignores the needs of salmon, orca, fishing families, Tribes, energy customers and communities across the Northwest.

With that historic agreement now withdrawn, and no other viable plan in place to protect salmon, the only path forward is a return to court.

In October 2025, conservation, fishing and renewable energy groups represented by Earthjustice, alongside the State of Oregon, resumed our long-standing court battle to prevent further extinctions and ensure healthy and abundant salmon and steelhead in the future.

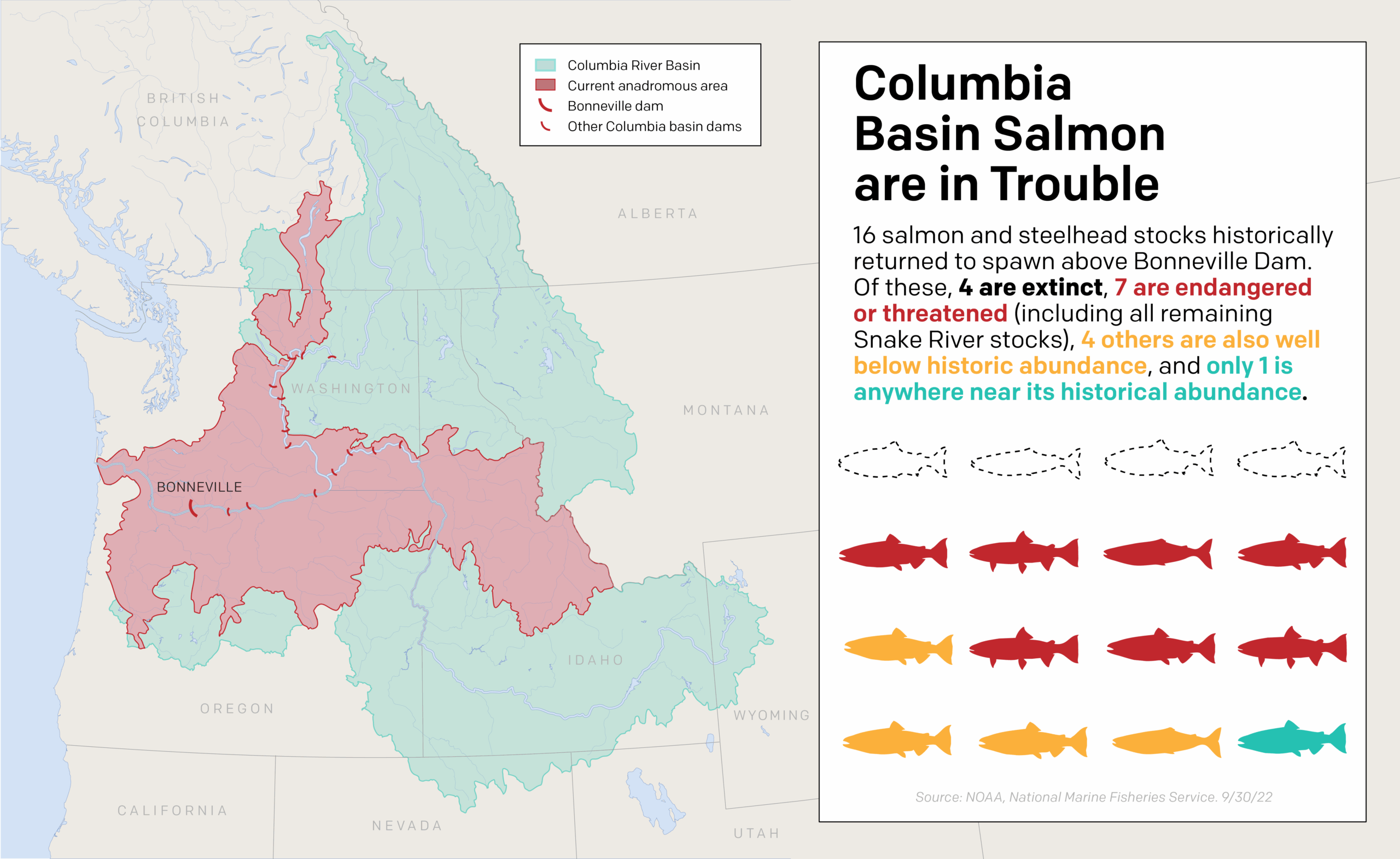

Columbia Basin Salmon Are in Trouble

We’ve already lost too many salmon and steelhead stocks to extinction — and many more are threatened with extinction today.

The entire Columbia Basin historically had 27 wild salmon and steelhead stocks, and 16 of these historically spawned above Bonneville Dam (the “Interior” Columbia Basin stocks).

Only one of these 16 stocks, the Mid-Columbia River Summer/Fall Chinook, is anywhere near its historical abundance.

Four are extinct within this entire geographic area, and several others are perilously close to being extinct.

Source

Rebuilding Interior Columbia Basin Salmon and Steelhead, NOAA 2022 (Table 2).

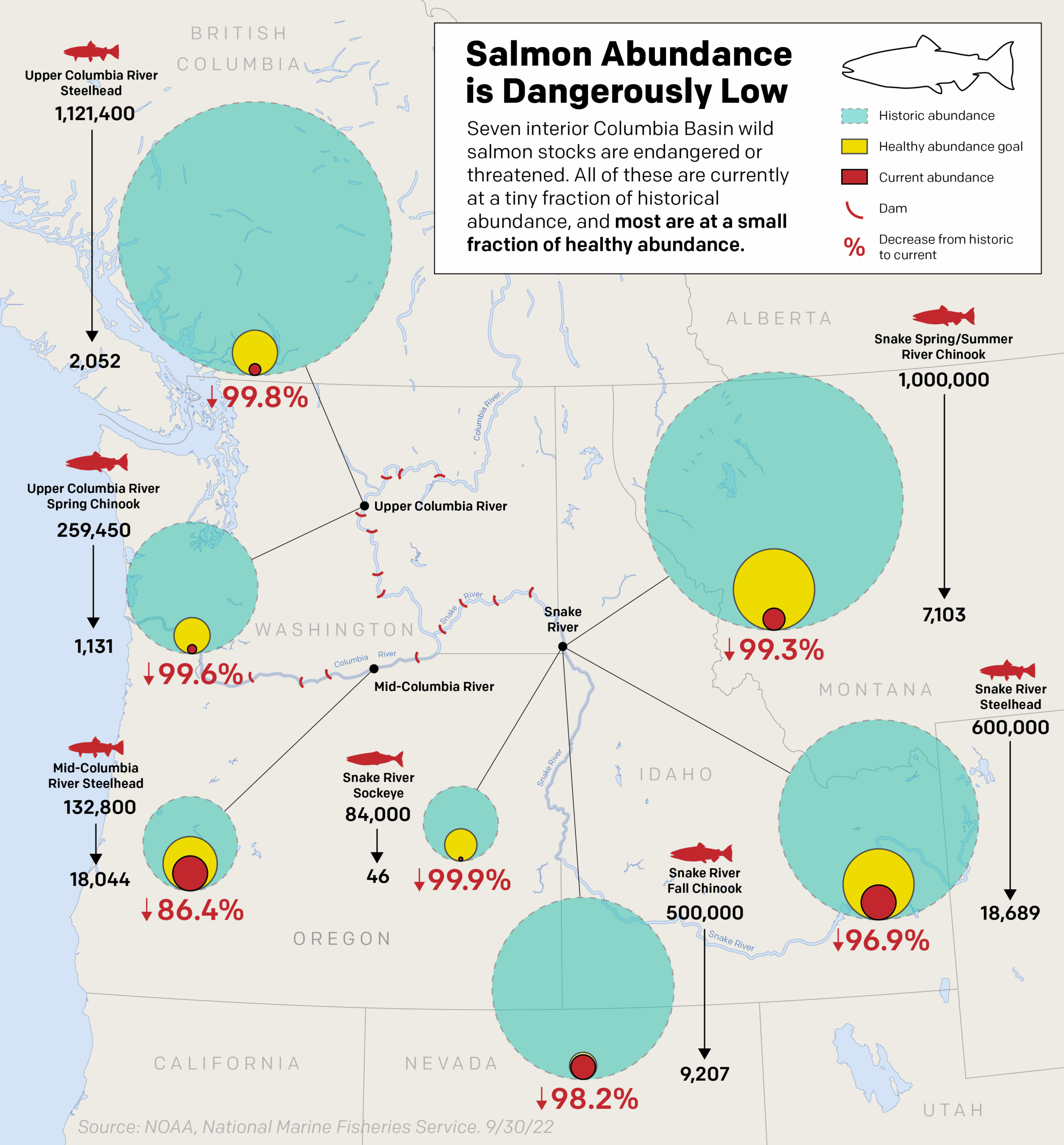

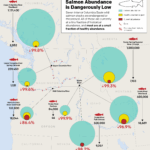

Salmon Abundance is Dangerously Low

Nearly all remaining wild salmon and steelhead stocks in the basin are in serious trouble, especially those that return to the Snake River to spawn.

Most remaining wild salmon and steelhead populations are less than 5% of their pre-1850s levels. Some, including several from the Snake River, are less than 1% of their historic levels.

Of these seven Interior Columbia Basin wild salmon stocks listed as endangered or threatened, none are doing well compared to historic abundance and only one stock, Snake River Fall Chinook, is approaching a healthy abundance goal.

Source

Rebuilding Interior Columbia Basin Salmon and Steelhead, NOAA 2022 (Table 2). The healthy abundance goal used in this graphic is the mid-level abundance goal set by the Columbia Basin Partnership.

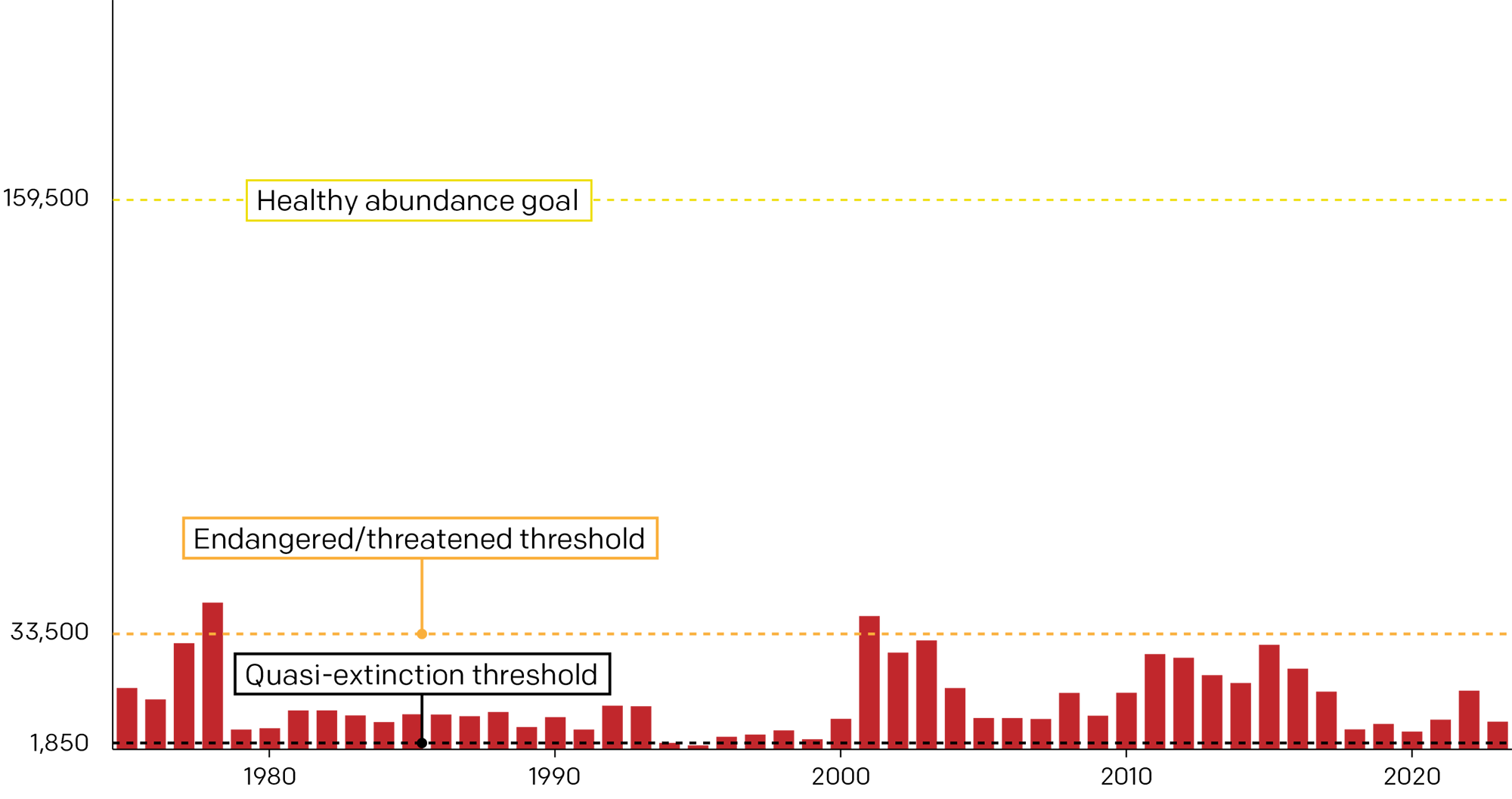

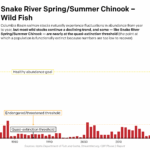

Acute Crisis in the Snake River Basin

While a few Columbia Basin species have experienced modest gains in recent years, others persist at dangerously low abundance. Looking only at returns that combine all species basin-wide can obscure dangerously low abundance of some key species. Snake River salmon and steelhead are among the species most in danger.

For some stocks, such as Snake River Spring / Summer Chinook and Snake River Steelhead, returns are approaching the “quasi-extinction threshold,” a level so alarmingly low that it is used as a bar for functional extinction because recovery may no longer be possible.

These declines are alarming — but federal, state, and tribal scientists have concluded that we can recover salmon to healthy abundance through centerpiece actions including breaching four dams on the lower Snake River and making comprehensive investments in habitat restoration and hatcheries, among other actions.

We can rebuild healthy and abundant salmon in the Columbia Basin while also ensuring reliable and affordable clean energy.

Snake River Spring / Summer Chinook are one of the species hovering closest to extinction — and time is running out to save them.

For decades, returns have been well below the threshold for protection under the federal Endangered Species Act, and returns are perilously close to functional extinction (the “quasi-extinction threshold”).

The endangered / threatened threshold and healthy abundance goals in this graphic are the “low” and “high” abundance numbers from the Columbia Basin Partnership.

Additional note

This graphic combines all remaining populations for wild Snake River spring / summer Chinook, but if you look at each population individually instead of species abundance, the picture is even worse.

Roughly a tenth of the remaining wild Snake River spring/summer Chinook populations are already below the quasi-extinction threshold and a third are expected to reach that functional extinction threshold in the coming years.

Source

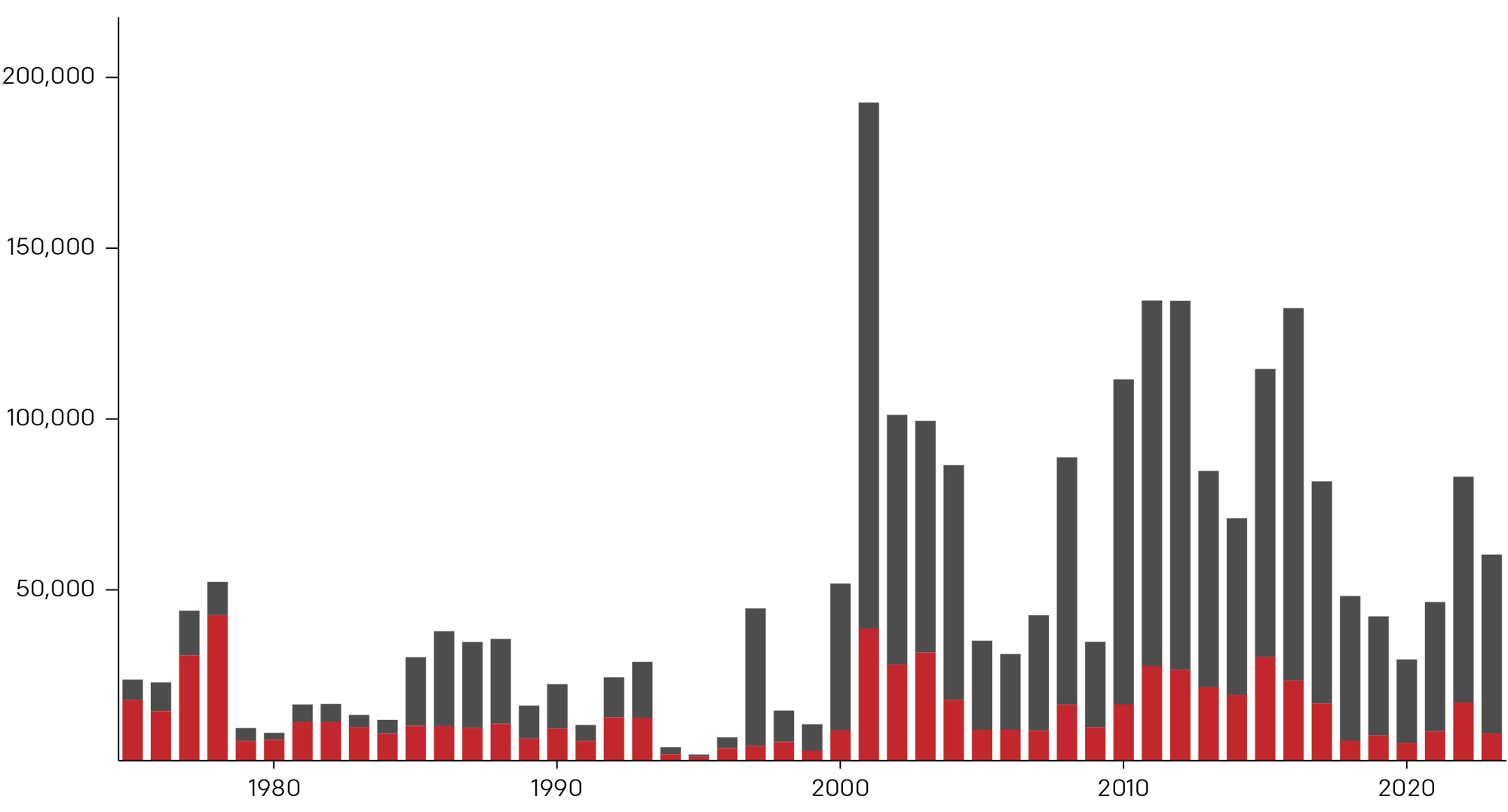

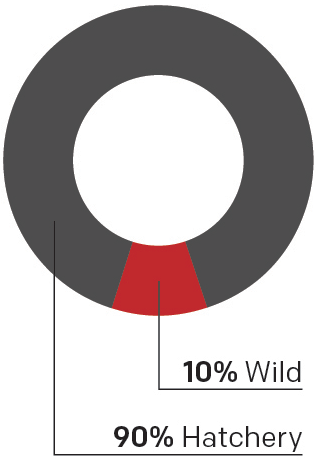

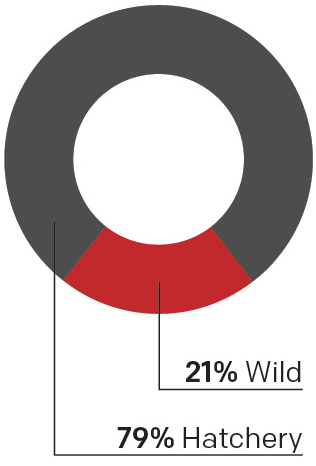

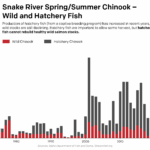

Hatchery fish are important to provide harvest opportunity, but hatchery fish alone cannot rebuild healthy wild salmon stocks — they lack the full genetic and geographic diversity of healthy, self-sustaining wild populations.

While hatchery production for some Columbia Basin salmon has increased, many wild populations remain critically low.

Combining hatchery and wild return numbers can mask the perilously low abundance of threatened and endangered wild runs.

Source

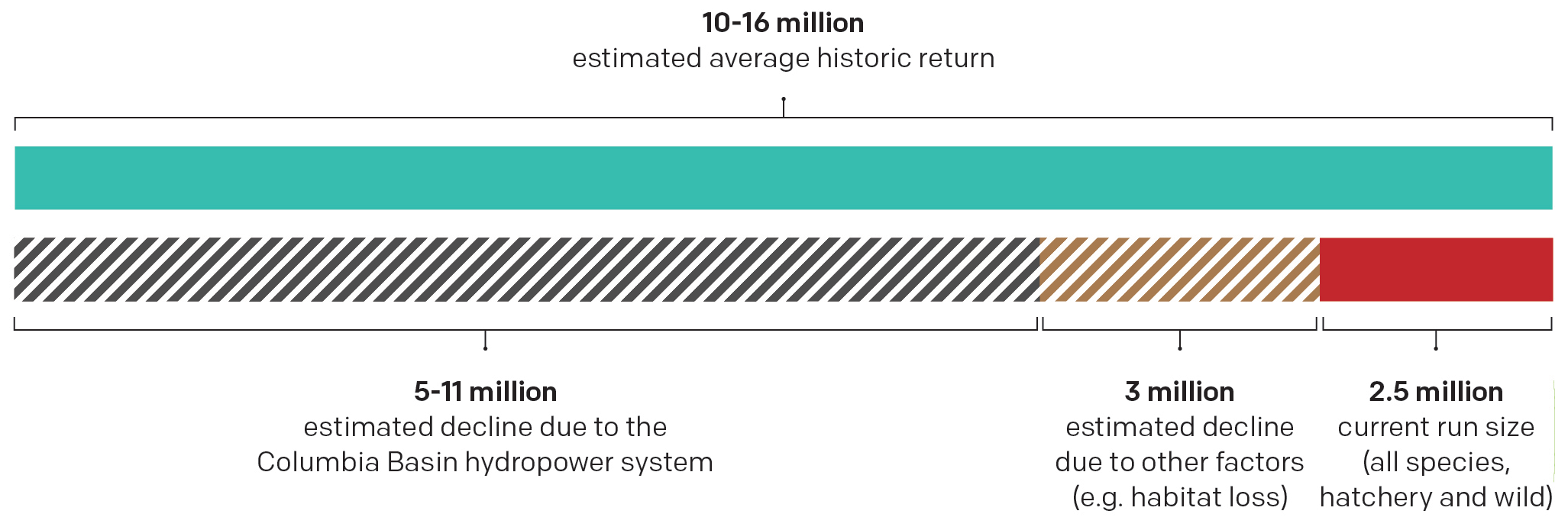

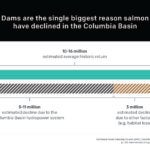

The Primary Role of Dams in the Decline in Columbia Basin Salmon

While many factors have contributed to the declines in these salmon runs, the Northwest Power and Conservation Council estimates that the development and operation of dams throughout the Columbia River Basin is responsible for declines of 5 to 11 million fish per year from historic levels, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that federal dams on the Columbia and Snake Rivers are the single greatest threat to most remaining salmon runs in their freshwater environment.

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council concluded in a comprehensive assessment that dams are the primary reason Columbia Basin salmon have declined.

Many factors have contributed to the demise, but today, the largest threat to salmon recovery and abundance for most runs is the operation of federal dams on the Columbia River and its tributaries.

Federal, state, and tribal scientists have identified four federal dams on the lower Snake River as a primary obstacle to salmon recovery for Snake River runs.

Recovering salmon to historic levels may not be possible, but scientists and policymakers have agreed that achieving stock-specific healthy abundance goals is possible.

Recovering salmon to a healthy abundance across the Columbia River Basin will require a suite of “centerpiece” actions identified by federal scientists, including breach of the four Lower Snake River dams and comprehensive investments in habitat restoration and hatcheries.

Source

Northwest Power Planning Council (1987), Columbia River Basin Fish and Wildlife Program (p. 38)

Lower Granite Dam. One of the four lower Snake River dams that Earthjustice is fighting to remove. Chris Jordan-Bloch / Earthjustice

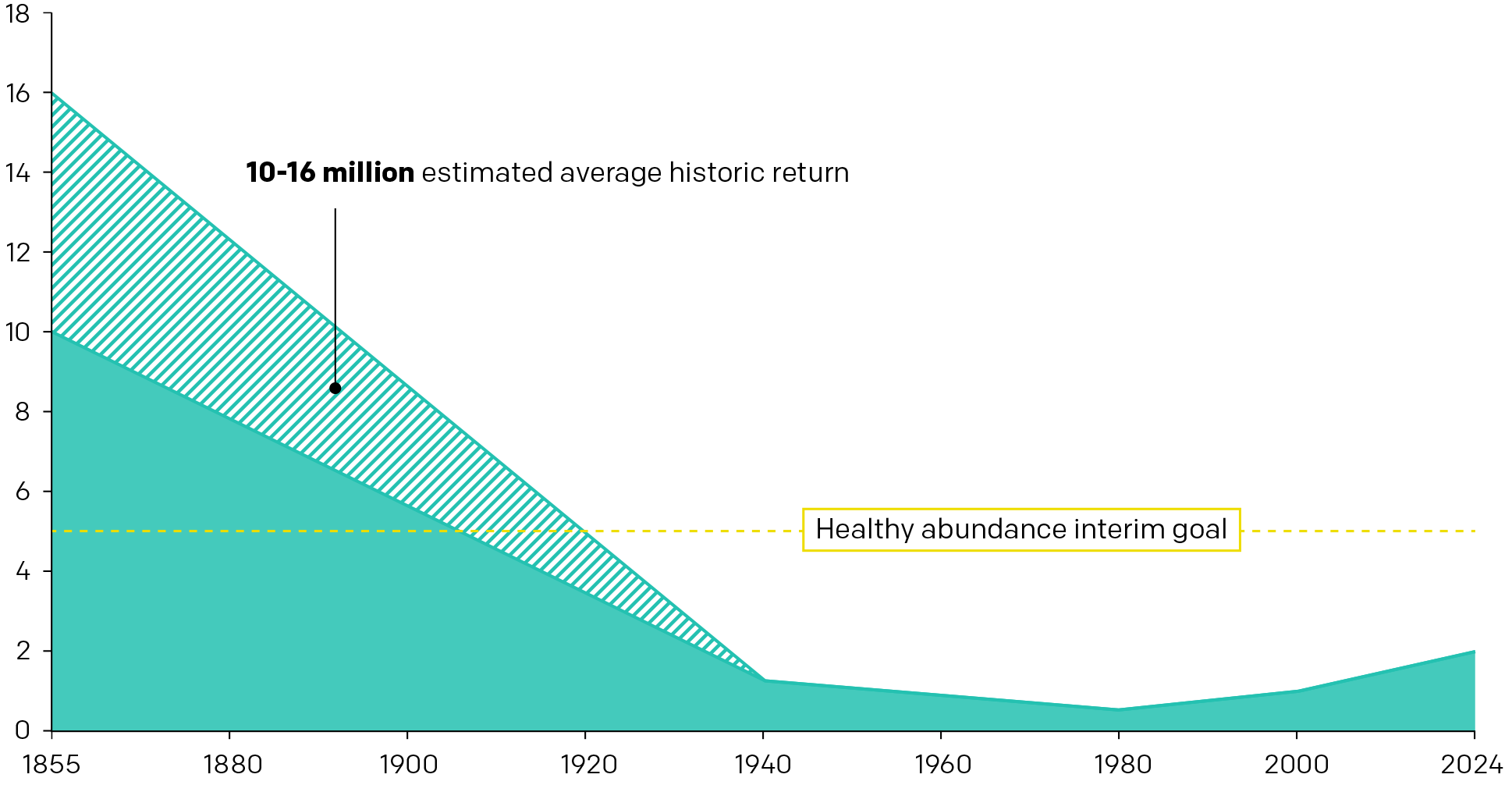

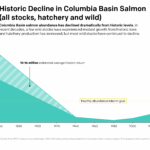

Understanding Columbia Basin Salmon Declines Over Time

Historically, between 10 to 16 million wild salmon returned each year to the interior Columbia River Basin to spawn. These salmon have suffered precipitous declines. Today’s critically low salmon returns are well below what healthy and abundant salmon runs should look like.

Fisheries scientists use several different measures of abundance — but by any of these measures, we’re falling short.

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council, established by the Northwest Power Act to address energy and conservation needs, set an interim abundance goal of 5 million salmon returning annually to the Basin by 2025. Current returns are less than half that number: today, only about 2.5 million fish (wild and hatchery combined) return annually to the basin.

Salmon abundance declined dramatically in the late 1800s through the late-1900s due to a combination of habitat degradation, excessive harvest, and the construction of dams across the Columbia Basin.

Declines continued until recent decades when hatchery production increased, resulting in modest gains in some areas.

However, most wild stocks have continued to decline and overall stocks, hatchery and wild, are still not even halfway to an interim healthy abundance goal of 5 million fish.

Many causes of historic salmon decline have largely been addressed and are no longer preventing salmon recovery.

For example, excessive harvest drove significant declines from the late 1800s and continued through the 1970s, declining as dam construction occurred.

Today, harvest is heavily regulated and ranks nearly last on the list of current threats to most runs.

Some misinformation to watch for is a claim by special interests who oppose dam removal that salmon returns have tripled since the Columbia Basin dams were constructed.

The increases they claim are only small improvements in overall counts at Bonneville Dam compared to baseline historic lows — and these numbers combine all returns across the basin.

While a few populations, such as Okanogan sockeye, have increased in recent years, other populations, including most that return to the Snake River Basin, are hovering on the brink of extinction.

Source

Northwest Power and Conservation Council, 1987 Columbia River Basin Fish & Wildlife Program report

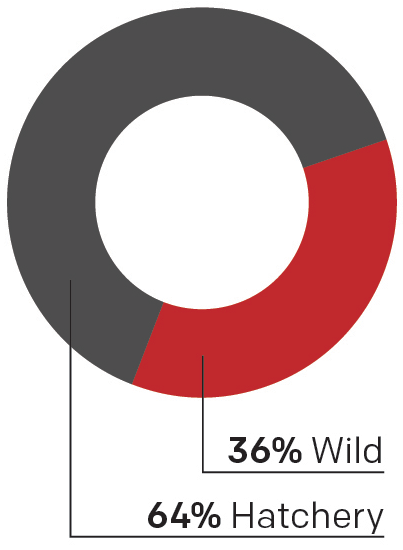

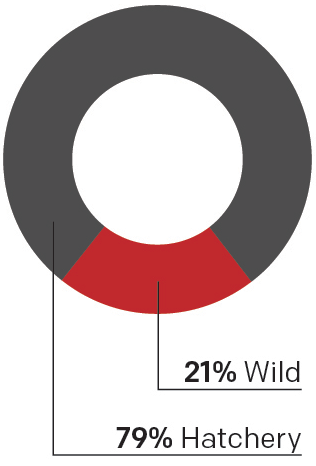

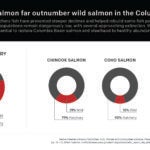

Hatchery Production Has Helped Sustain Fisheries — But Not Enough

Hatchery production began in earnest in the 1940s to mitigate for the construction of federal dams. Even though hatchery production has increased since then, most federal hatchery facilities in the Columbia Basin are not meeting, and have never met, their mitigation responsibilities identified when the dams were built.

Hatchery fish are important to increase harvest opportunities, but they lack the full geographic and genetic diversity of sustainable "wild" or natural-origin salmon runs needed for Northwest salmon to continue to thrive.

In recent years hatchery fish have accounted for around 64% of salmon returning to the Columbia Basin.

This percentage varies dramatically by species — and some of the largest and most valuable species, such as Chinook and steelhead, have the lowest percentage of wild fish returning.

Other smaller and less prized species, such as chum salmon, do not have significant hatchery returns.

Source

Columbia Basin Partnership Task Force Phase 1 Report (p.76-77)

We must prevent salmon extinction. Urge your Congressmember to support healthy and abundant salmon in the Columbia and Snake Rivers.

About the Infographics

Earthjustice produced these infographics based on publicly available data from federal agencies, states and tribes to help explain how Columbia Basin salmon and steelhead remain in serious trouble.

Special interest groups who oppose any dam removals erroneously claim no further actions will be needed to restore salmon, but the reality is startlingly clear: Many Columbia Basin salmon and steelhead species are hovering on the brink of extinction. And time is running out to save them.

Each of these infographics is downloadable.

- You may use and share these infographics to help share the plight of these iconic species and the need for Columbia Basin restoration.

- Please credit Earthjustice, and email us at media@earthjustice.org if you have any questions.

Additional Resources

- Fish Facts: Columbia Basin Salmon, Steelhead, and Other Native Fish in Crisis (Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission for the Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs and Yakama Tribes, and the states of Oregon and Washington)

- Columbia Snake River Campaign Fish Facts Briefing (Jay Hesse, Director of Biological Services, Nez Perce Tribe Department of Fisheries Resources Management)

- Department of the Interior: Historic and Ongoing Impacts of Federal Dams on the Columbia River Basin Tribes

- Earthjustice handout containing selected graphics from this webpage

- Earthjustice timeline: A Long Fight to Restore Snake River Salmon