Making America’s Waters Burn Again

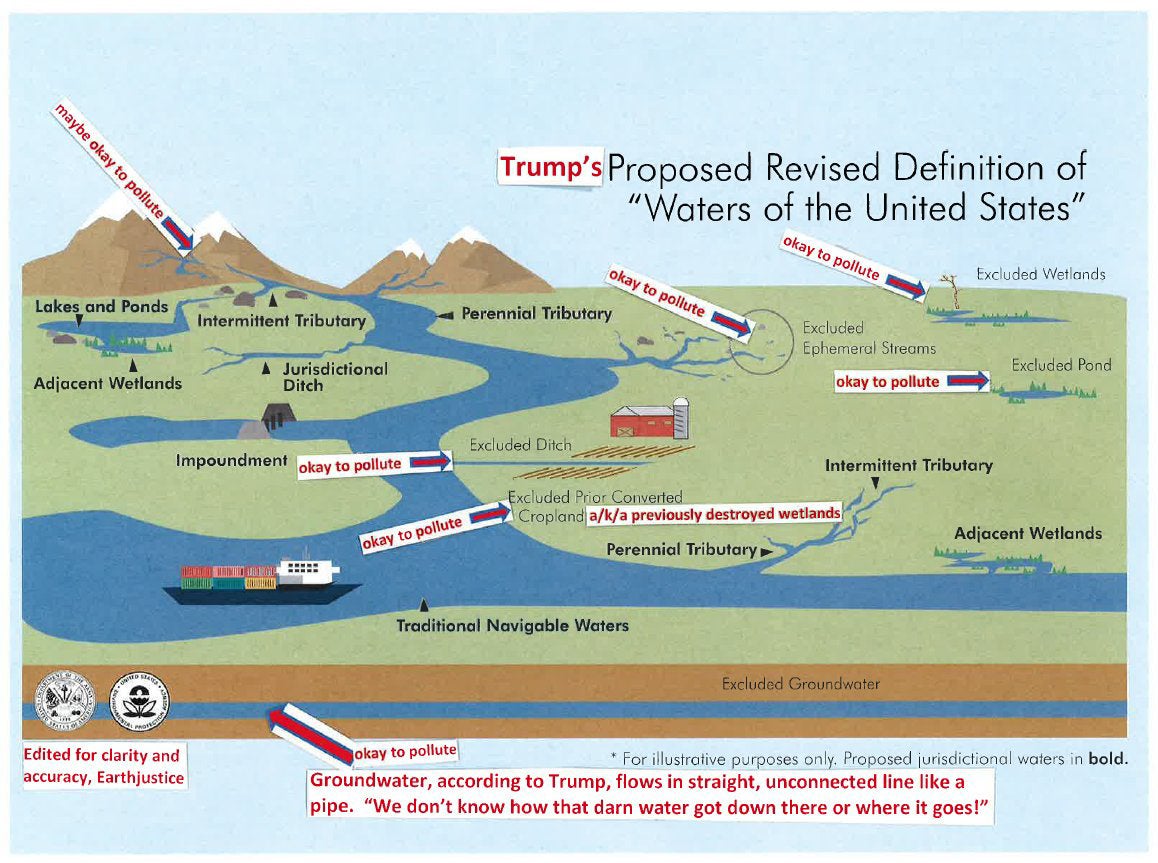

The Trump administration seeks to strip the Clean Water Act’s protections from an overwhelming number of our waterways. We're fighting back.

The Trump administration’s new Dirty Water Rule seeks to strip the Clean Water Act’s protections from an overwhelming number of our waterways and return our water to levels of pollution we last saw before the Clean Water Act’s enactment in 1972.

The Trump administration announced this major environmental rollback on December 11, 2018, amidst much fanfare in the historic EPA map room.

After multiple failed attempts to repeal or delay the Obama administration’s Clean Water Rule, which defined the term “waters of the United States” in the Clean Water Act, the Trump administration is now proposing to wholly replace the Clean Water Rule with a new rule. This proposed rule goes far beyond a reversal of the Clean Water Rule’s definitions, introducing new water exclusions that have never been in place before and gutting the Act’s safeguards, threatening the sources of drinking water for millions of people as well as wildlife habitats and outdoor recreation opportunities.

Dirty Water Basics

The Dirty Water Rule proposal removes basic Clean Water Act protections for huge percentages of waters by restricting the types of waters covered by the Act. The Clean Water Act applies broadly to all “waters of the United States,” but the Trump administration proposes to shrink that term to something more like “waters of the United States that are big enough for boating.” While the rule retains protections for larger “navigable” waterways like rivers, it removes protections for a gut-wrenchingly large proportion of upstream and underground waters that flow downstream into those larger waters, making them conduits for conveying our nation’s pollution to drinking water sources and other critical waters.

When it comes to the waters affected by this action, the numbers are staggering:

- Nearly one in every five streams nationwide

- Over half of all remaining wetlands nationwide

- All groundwater

- Many other tributaries, lakes, and ponds

In the western U.S., these numbers are much higher. For example, close to 40 percent of the length of streams will lose protections in arid western states, where rain-driven “washes” or “arroyos” are common. In the Pecos River Basin, which spans parts of New Mexico and Texas, up to 91 percent of streams and 62 percent of wetland acres will be excluded.

Contrary to the Trump administration’s unscientific claims, these upstream waters are not mere isolated, unconnected waters. Instead, they form essential aquatic networks that act like the country’s capillaries. For example, upstream tributaries move all sorts of physical and chemical compounds — including pollutants — downstream through their flows. Wetlands are also connected to other waters in a myriad of ways, and they perform critical jobs for humans, especially during this time when we’re experiencing more frequent and intense storms due to climate change. Wetlands naturally absorb flood waters, filter pollutants, and recharge groundwater reserves, as well as provide habitat for fish, amphibians, insects, birds, and mammals. Because they attract such a diverse array of species and provide many kinds of food, EPA has called wetlands “biological supermarkets.” Wetlands are so important, they even have their own international treaty.

The loss of so many upstream tributaries and wetlands to unfettered pollution will carry potentially catastrophic consequences for anyone who drinks water.

A Foundation of Falsehoods and Misdirection

What is driving the Trump administration’s proposal? From the outset the push to gut clean water protections was founded on claims that were less than accurate, in some cases downright false.

When the Obama administration proposed science-based regulatory adjustments aimed at clarifying the existing scope of the Clean Water Act and protecting drinking water sources, Republicans portrayed the effort as a left-wing federal power grab. In fact, Obama’s proposal largely tracked an earlier guidance document issued by the George W. Bush administration — and it was even further weakened before it was finalized in an attempt to appease members of polluting industries who complained that they should have even fewer obligations to prevent water pollution.

But polluting industries weren’t satisfied. Despite the fact that farm operations are almost entirely exempt from the Clean Water Act, industry associations that represent the interests of mega-industrial agricultural operations exploited the image of the struggling small farmer to justify shrinking clean water requirements that apply to everyone else, from mining operations to oil refineries to scrap-metal junkyards. When scandal-ridden Scott Pruitt rose to the helm as the industry favorite for administrator of the EPA under the Trump administration, he kept repeating industry talking points like the false claim that farmers would need to get permits to walk through puddles on their lands.

The misdirection continues in the proposed rule, with EPA Acting Administrator Andrew Wheeler claiming that the rule is about clarifying the role that the 50 states play in protecting water quality. In truth, the states already know that they retain very broad authority under the Clean Water Act, including the primary role in setting their own standards for cleanliness, issuing permits to protect state waters for uses like drinking, swimming, boating, fishing, wildlife, and commerce, and enforcing their permit requirements for companies that could pollute their waters. The sky is the limit for state water quality protections, as long as they don’t drop below the minimum floor provided by the federal Clean Water Act. So when Trump officials claim they want to expand the scope of “state protected waters,” what they really mean is that they want to pull the floor out from under a whole slew of waterways that currently enjoy strong federal protections.

Poisoned, Burning Waters Hurting Our People — an Outcome We Can’t Accept

Congress adopted the Clean Water Act in response to some very practical problems: Waters were so heavily polluted they would occasionally catch on fire, and drinking water sources were seriously contaminated. Members of Congress talked about how the Act was “vitally needed to undo the damage we have done to our Nation’s waters,” as “lakes and rivers and streams grow filthier by the day,” and there were “potentially harmful levels of chemicals in one-third of our drinking water supply.” There was also a solid bipartisan understanding of the interconnectedness of small streams and wetlands with larger downstream waters. In order to attain the objective of the Act — “to restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters” — the Act’s sponsors on the Hill said that they “fully intend that the term ‘navigable waters’ be given the broadest possible constitutional interpretation,” in order maintain the “natural structure and function of ecosystems.”

Has Trump’s EPA gone backward in its understanding of these basic ecological concepts? Not exactly. In fact, the Trump administration’s own economic analysis openly admits that this proposal would severely undercut the effectiveness of every major Clean Water Act program — further proving that they would rather protect polluting industry than our water resources and public health. They predict a host of environmental effects: more streams and wetland habitats destroyed or degraded, increased flood risk, greater pollutant loads, increased risk of more frequent and larger oil spills, and less effective oil spill clean-up response. In terms of economic impacts, the agencies predict reduced ecosystem values (meaning loss of the valuable functions that wetlands and small streams perform in filtering and holding back pollution), greater flooding damages, greater restoration costs, greater drinking water treatment and dredging costs, and greater oil spill damage along with greater oil spill response costs.

EPA and the Corps suggest that voluntary programs and financial assistance grants will pick up the slack. While these sorts of voluntary approaches have been in place for more than four decades, water quality in many states is still poor, and many states have allowed more than half of their wetlands to be destroyed. Worse, the Trump agencies’ own analysis warns that it is “impossible to predict with certainty” whether states will actually keep their existing programs; some may simply drop the overlapping protections they currently have in place for waters that would no longer be protected under the federal Clean Water Act because of this proposal. Indeed, it is very likely that if this rule is finalized it will trigger a race-to-the-bottom in which states attempt to outdo each other in weakening their water quality requirements in order to attract polluting businesses.

Pushing back

Upon announcing this flawed and destructive proposal, the Trump administration said they would be taking comments on it for only 60 days. Earthjustice has been fighting back against the Trump administration’s attempts to weaken and shrink the Clean Water Act in the courts, and we intend to continue bringing a diverse collection of voices and perspectives to bear as we resist this all-out attack on clean water. Join us in speaking out against this flawed proposal.

Earthjustice’s Washington, D.C., office works at the federal level to prevent air and water pollution, combat climate change, and protect natural areas. We also work with communities in the Mid-Atlantic region and elsewhere to address severe local environmental health problems, including exposures to dangerous air contaminants in toxic hot spots, sewage backups and overflows, chemical disasters, and contamination of drinking water. The D.C. office has been in operation since 1978.