A New Front in the Battle Against Coal Exports: Treaties

Native American tribes in the Pacific Northwest are invoking an unusual source of legal authority—treaties—to block massive coal, crude oil and tar sands development.

This page was published 10 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

A new front has opened in the epic battle to block projects that threaten to turn the Pacific Northwest into a hub for fossil fuel exports. While citizens and regulators have been duking it out over environmental reviews and compliance with laws like the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act, the Lummi Indian Nation has invoked a very different source of law—a 160-year-old treaty—to block a massive coal port near Bellingham.

In 1855, decades before Washington even became a state, Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens and the leaders of a number of Salish Sea tribes signed the Treaty of Point Elliot. In it, the tribes ceded title to a portion of their ancestral lands in exchange for reservations, payments and—most importantly—a commitment that they’d be able to fish, hunt and gather at all of their “usual and accustomed” places in perpetuity.

To say that the salmon, shellfish and other gifts of the landscape are central to the economies and cultures of the signatory tribes doesn’t even begin to tell the whole story. In one 1906 case, the U.S. Supreme Court tried to capture the centrality of reserved fishing rights to Northwest tribes: they were “not much less necessary to the existence of the Indians than the atmosphere they breathed.” The current fossil fuel export proposals—which would put dangerous and toxic materials into the heart of the tribes’ treaty-reserved fishing areas—are nothing less than an existential threat to the people who have depended on this landscape since time immemorial.

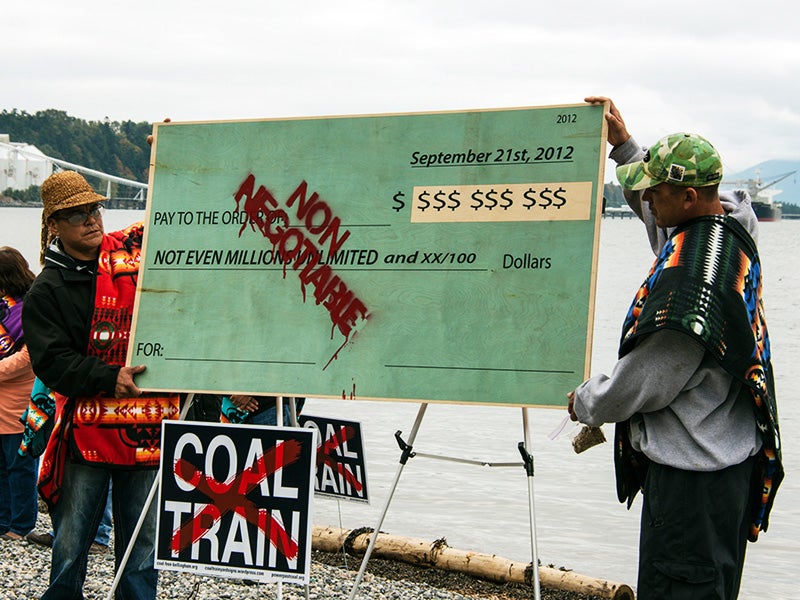

The Treaty of Point Elliot represents both a legal and a moral obligation on the part of the U.S. government—and the American people—to protect that way of life. In January of this year, the Lummi, a signatory tribe to the treaty, called in that debt. The Lummi formally asked the United States government to deny permits for a massive, 48 million ton per year coal terminal adjacent their reservation just north of Bellingham. The proposed Gateway Pacific Terminal would sit on Lummi sacred land, and hundreds of the largest vessels on the planet would thread through prime fishing areas on their way to load up on coal. Lummi members made their feelings about the project—that no amount of money could buy their support—clear in October 2012 when they burned a symbolic check for limitless dollars.

The law is quite clear: the only way for the government to honor this longstanding obligation is to deny the coal port permit. Federal court precedent says that where a tribe opposes a project based on its impacts on treaty-reserved fishing, a federal agency cannot authorize anything more than a “de minimis” impact. (That’s legalese for “practically nothing.”) The proposed Gateway Pacific Terminal, which would transform a pristine site in one of the Salish Sea’s most productive and cherished coastal waters into a polluted industrial zone, is anything but “de minimis.”

The Lummi’s stand against Big Coal is not isolated. Throughout the region, First Nations and Native American tribes are standing strong against more fossil fuel development. For example, Earthjustice represents four U.S. tribes in an effort to block a massive tar sands pipeline in Canada that would put treaty fishing areas at risk of catastrophic oil spills. Tribal opposition and impacts to fishing helped convince the state of Oregon to deny a permit for another coal port on the Columbia River. And a small First Nation in British Columbia stunned the world with a unanimous vote to reject more than a billion dollars to allow a liquefied natural gas terminal to be built on its traditional lands.

There are plenty of good reasons to oppose plans to build coal and oil transportation depots throughout our region: oil trains derail and cause disasters, crowds of tankers would threaten spills in the Salish Sea and communities would be bisected by staggering increases in rail traffic—all so we can lock in even more dependence on polluting fossil fuels. Communities across the Pacific Northwest have built a passionate and effective movement to stop these projects, and they are winning.

Yet another reason to oppose fossil fuel development in the Pacific Northwest is that it perpetuates the centuries-old legacy of exploitation of native peoples and their lands, fish and cultures. Lummi tribal member Jewell James has likened the explosion of coal, oil and gas projects to a 21st century version of the “Trail of Tears.” But the region’s tribes are writing a new ending to that tragic story, standing in firm opposition to projects that threaten their homes, their way of life, their sacred landscapes and their treaty rights. The question now is whether our government will keep the 160-year-old promise embodied in the Treaty of Point Elliot by rejecting the coal port. We expect a decision this fall. Stay tuned.

Established in 1987, Earthjustice's Northwest Regional Office has been at the forefront of many of the most significant legal decisions safeguarding the Pacific Northwest’s imperiled species, ancient forests, and waterways.