In Harvey’s Wake, Residents Near Houston Industry Suffer Pollution Spike

Refinery shutdowns leave communities vulnerable to releases of hazardous emissions

This page was published 8 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

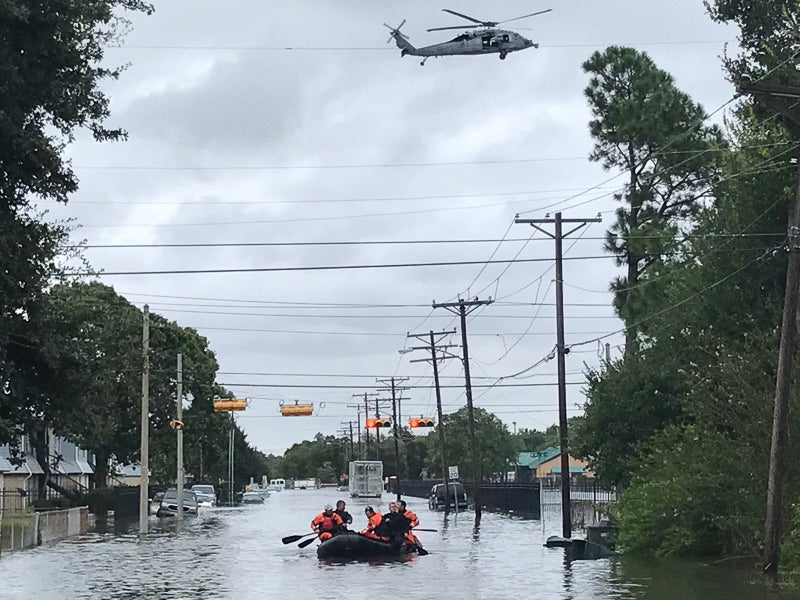

Residents in Houston, Texas and the Gulf region are still reeling from the disastrous effects of Hurricane Harvey, which dumped more than 50 inches in some areas this week, displacing thousands, and causing untold loss of life.

Although some were able to avoid the flooding to whatever extent they could by evacuating and uprooting their lives, communities near the Houston Ship Channel are facing a different problem: a barrage of possible hazardous pollution stemming from the response of refineries and chemical plants that have shut down operations.

When refineries and chemical plants are shut down or are in the process of shutting down, they often release thousands of tons of air pollution that can lead to premature death, according to a 2012 report from the Environmental Integrity Project.

By Tuesday, some 13 refineries had shut down operations including seven in Houston/Galveston and six in Corpus Christi, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. On Wednesday, the nation’s largest refinery in Port Arthur announced that it was shutting down its refinery due to rising floodwaters near the Texas-Louisiana border.

Now, people nearest oil refineries are living day-to-day without knowledge of exactly what’s being released and in what quantities. What they are being hit with are pungent chemical or gas-like odors in addition to headaches, sore throats and itchy eyes.

One of those suffering from the odors and physical impacts, including chest pain and a sore throat, is Bryan Parras, who lives in the Eastdown community just a few miles away from Manchester, where a Valero refinery is located as well as three chemical plants.

Parras is a member of Tejas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services. The group, with the assistance of Earthjustice, successfully sued the EPA in 2012 to bring about more stringent national refinery standards that were finalized in 2015.

Children who live within two miles of the Houston Ship Channel have a 56 percent higher incidence of leukemia than those who live 10 miles away.

Parras told the Houston Press that the soreness and chest pain that he normally suffers when he takes people out on toxic tours is now harming him in his home.

“The stuff was getting sucked into my home through the window and air conditioning units,” he told the Press.

Some of the nation’s highest levels of cancer-causing chemicals benzene and 1,3-butadiene were identified in the Manchester community, which is mostly Latino. The University of Texas School of Public Health found that children who live within two miles of the ship channel have a 56 percent higher incidence of leukemia than those who live 10 miles away.

Chemical plants are often in close proximity to oil refineries. The Chevron Phillips Chemical Plant in nearby Sweeny, Texas—50 miles from Houston—has notified the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) that it expected to exceed permitted limits for multiple hazardous pollutants – including 1,3-butadiene, benzene and butane – during the shutdown. In addition, it reported releasing 100,000 pounds of carbon monoxide, 22,000 pounds of nitrogen oxide, 32,000 pounds of ethylene and 11,000 pounds of propane.

On Thursday morning the Arkema Chemical Plant, 25 miles from Houston, suffered two explosions when containers carrying combustible substances lost refrigeration. The explosions prompted authorities to order the evacuation of people living within 1.5 miles of the plant and 15 law enforcement officers ended up in the hospital due to smoke inhalation.

After taking office in January, the Trump administration immediately delayed a rule by the Obama administration that would require facilities like the Arkema plant to assess practicable safety improvements and do a better job coordinating and sharing information with first responders. Arkema stores at least two types of highly dangerous chemicals covered under the rule, in addition to many other dangerous compounds.

Air quality monitors turned off

Unfortunately, the residents of Manchester and other communities who are suffering the impacts of this pollution may never find out how much they were exposed to. That’s because the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality shut off their air quality monitors that would capture emissions reportedly out of concern that possible water and wind damage could result if they were operating.

Those who live nearest the nation’s roughly 150 refineries, in what are called fenceline communities, are twice as likely to be low-income and communities of color than those living elsewhere in the U.S.

Bakeyah Nelson, executive director of Air Alliance Houston, which advocates for clean air and was also represented by Earthjustice in the 2012 lawsuit, told the Houston Press that pollution coming from these refineries due to the hurricane is a dire threat to public health.

“When petrochemical plants prepare for storms, they release thousands of pounds of pollutants into the air. This pollution will hurt public health in Houston. It is a stark reminder of the dangers of living near industry,” Nelson said.

As advocates for environmental justice, Earthjustice works to promote clean energy, end the reliance on fossil fuels and reduce the amount of harmful pollution that fenceline communities face.

Earthjustice’s Washington, D.C., office works at the federal level to prevent air and water pollution, combat climate change, and protect natural areas. We also work with communities in the Mid-Atlantic region and elsewhere to address severe local environmental health problems, including exposures to dangerous air contaminants in toxic hot spots, sewage backups and overflows, chemical disasters, and contamination of drinking water. The D.C. office has been in operation since 1978.