Coming Clean: Hydropower’s Dirty (Energy) Secrets

Dams are often touted as being green, but a deeper looks uncovers some dirty truths about their environmental impact.

This page was published 11 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

With the release of our clean energy map, we’ve gotten a lot of questions about why we’re discounting hydropower as a source of clean energy. After all, hydropower is often perceived to be emissions-free, much like solar and wind power.

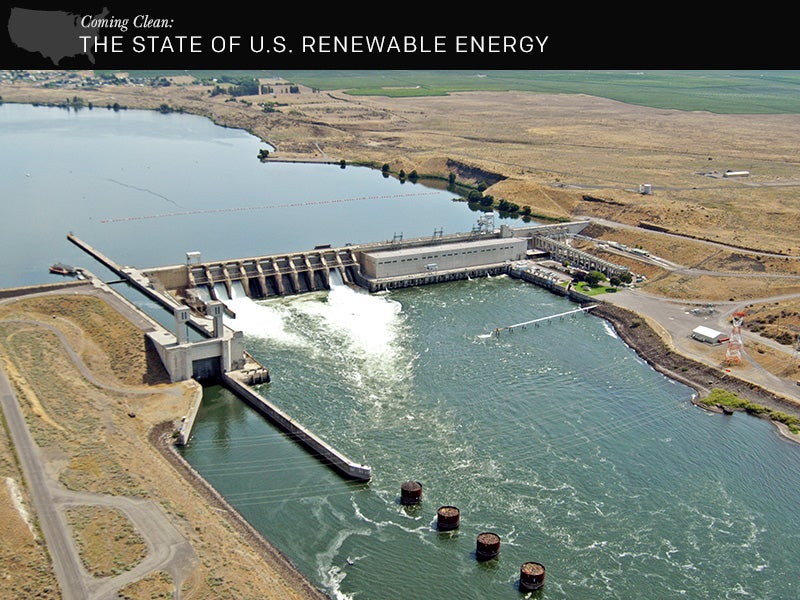

Washington State, for example, looks like a clean energy leader at first glance. The state saw the most dramatic reduction in carbon pollution between 2005–2012, cutting emissions by 54 percent. It also leads the nation in electricity generation from renewable sources, with three-quarters of its energy coming from hydropower. But some of that hydropower comes at a high cost.

Damming rivers can significantly disrupt and harm the migration of fish, affect the natural morphology of the waterway, and has been shown to reduce water quality. Since 1988, when the president of the American Fisheries Society sounded the alarm that only 2,000 of the typical 200,000 adult king salmon had returned to California’s Sacramento River to spawn, Earthjustice has been fighting major water diversion projects and harmful hydroelectric dam operations along the West Coast.

For example, four older dams on the lower Snake River in Washington pose a significant and unnecessary obstacle for migrating salmon. While some tout them as an emissions-free source of power, these four dams kill salmon on their way to and from the habitat they will need most to survive in a warmer world—the high-altitude, cold waters of protected wilderness in central Idaho. In addition, the operation of these dams has caused violations of state water quality standards. Because they account for so little of the region’s electricity, the power these dams produce can easily be replaced with other kinds of truly clean energy that don’t create major ecological concerns for our rivers.

These and other large dams on the Columbia River have transformed the Columbia and lower Snake rivers from the largest free-flowing highway for migrating salmon into slackwater reservoirs, drastically altering natural river flows and posing lethal obstacles to salmon migration. It is difficult to classify as “clean” a source of energy that threatens the extinction of several species of fish.

Then comes hydropower’s dirtiest secret. At the point of generation, hydroelectricity is emissions-free. But the entire lifecycle of the hydroelectric plant cannot be ignored. Massive amounts of cement are used in the construction of a dam—and studies suggest that cement contributes to as much as 5% of global CO2 emissions. Another huge concern is the greenhouse gas emitted from dam reservoirs. In these man-made reservoirs, rotting organic matter can release significant amounts of methane—a greenhouse gas 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide. The amount of emissions from such reservoirs is too large to ignore; in fact, scientists estimate that it contributes to 4% of human-caused climate change.

In Alaska, the state has set a high (albeit voluntary) bar for renewable generation, hoping to generate 50% of the state’s electricity from renewable resources by 2025. To achieve that, the state is looking at building one of the tallest and most expensive dams in the nation, the proposed Susitna-Watana hydro project, which could generate enough power for two-thirds of the state’s population. Like the dams along the Snake and Columbia Rivers, that project could come at the cost of a healthy and vibrant ecosystem and industries such as fishing and tourism that rely on it. At the same time, the CO2 emissions from constructing a large dam and the methane created from flooding a reservoir means the electricity generated may not be as clean as promised.

The problem with hydropower is that it is touted as a clean energy source but a deeper look uncovers its numerous dirty secrets. Hydropower is not only being pursued as a clean energy option in Alaska, but around the world as global leaders look to develop climate and energy solutions. There are more than 250 dams proposed for the Amazon basin alone, and Earthjustice partners at AIDA have been fighting to stop them. A cleaner energy future is ahead of us, but our path towards it takes careful evaluation of the choices before us.

About this series

The Clean Power Plan sets different goals for each state to reduce its carbon emissions by 2030. As one pathway to meet those goals, the EPA suggests a renewable energy target for each state.

However, many of the states are already on track to meet or even exceed those renewable aims. Find out how your state stacks up on the road to the cleaner energy future at Coming Clean: The State of U.S. Renewable Energy.

Don’t miss previous installments of the Coming Clean blog series:

- Hawaiʻi: The Launchpad for Clean Energy Liftoff

- California: How the Golden State Is Winning the Renewable Energy Race

- Kentucky: A Ray of Light in Coal Country

- Ohio: How Fossil Fuel Interests Unraveled the Buckeye State’s Renewable Energy Progress

The International Program partners with organizations and communities around the world to establish, strengthen, and enforce national and international legal protections for the environment and public health.

Established in 1987, Earthjustice's Northwest Regional Office has been at the forefront of many of the most significant legal decisions safeguarding the Pacific Northwest’s imperiled species, ancient forests, and waterways.