Obama Is On a Fast Track to Solidify Secret European Trade Deal

Yesterday, the Senate granted President Obama the authority to negotiate at least two massive trade agreements, one of which you’ve probably never heard of.

This page was published 10 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

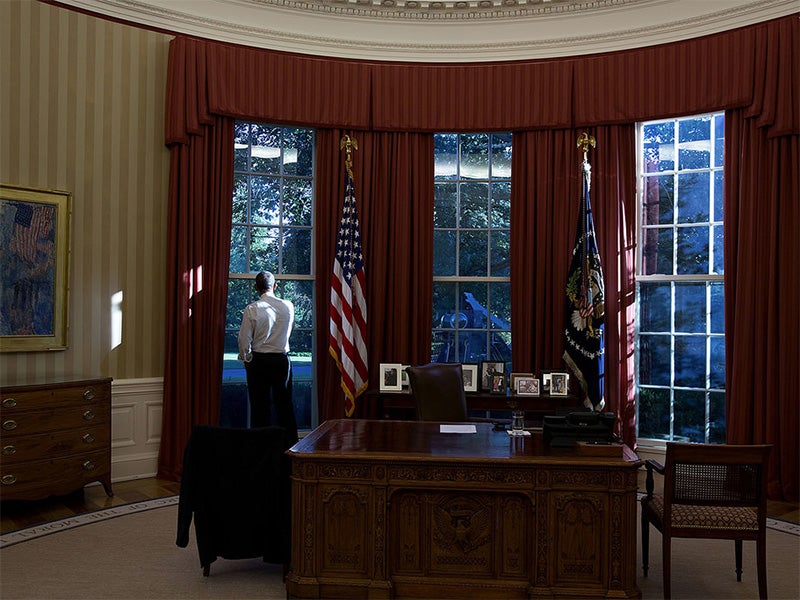

Yesterday, after much wrangling by President Obama and congressional Republicans, a bill giving Obama fast-track authority to negotiate international trade agreements passed in the Senate. It’s now headed for Obama’s desk.

The bill gives the president the ability to negotiate agreements with other nations that Congress will have to accept or reject with a simple yes or no majority vote. This authority will last for six years, well after Obama’s successor takes office. Congress won’t be allowed to amend any of the agreements’ provisions or open them up to debate. Simply put, this means the public won’t see specific provisions in major trade agreements until it’s effectively too late to change them. The administration is currently negotiating two gargantuan trade deals, one with Pacific Rim nations called the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and a lesser known one with the European Union called the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

We’ve been seeing a lot of news coverage of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, but we should consider that the TTIP may be even more important. Any trade agreement with Europe will have a huge impact because European corporations account for a large portion of foreign investors in the United States—cumulatively more than the Asian-Pacific countries involved in the TPP. Of the top 10 countries making direct investments in the United States, seven are in the European Union.

Earlier this month, the European Parliament stalled its vote on the TTIP. According to European Parliament president Martin Schulz, this delay was caused by amendments that have been tacked onto the resolution, not by widespread opposition to the deal. Nevertheless, dissent has been ramping up, especially among environmentalists, labor unions and consumer advocacy groups.

The TTIP would apply TPP-style measures to trade between the United States and Europe, including controversial investor-state dispute settlement provisions. These settlement provisions allow investors to bring lawsuits directly against the country hosting their investments when they believe government actions threaten to reduce their profits. Because the disputes are heard in secretive international tribunals whose rulings are automatically enforceable in domestic courts, the provisions allow corporations to challenge government policies, such as pollution reduction targets, without being accountable to those governments or their citizens. This all but guarantees corporate interests will trump environmental concerns.

Among other worries are the implications for natural gas extraction because these trade agreements allow corporations to sue local, state and national governments to stop environmental laws like fracking bans. For example, investment provisions would allow oil and gas corporations to sue if they’ve made investments in a place that later adopts a ban or moratorium on fracking. This means a natural gas company invested in, say, New York—a state that finally won its fight to ban fracking in 2014—could sue the state government and potentially overrule the ban. Furthermore, once a foreign country becomes our trading partner, it is effectively allowed to import unlimited amounts of U.S. natural gas—a provision that could increase demand for fracking in the U.S.

Although the TTIP will likely include environmental protection measures, it’s unlikely they will be enforced. Protections are dependent on parties to the agreement enforcing them, and historically, trade is the highest priority in trade agreements. In fact, there are very few examples of governments using a trade agreement to enforce environmental protections.

Much as the TTIP could overrule national laws that protect the environment by keeping polluters in check, the president’s push for fast-track authority means he’s overridden Congress’ mandate to be a check on presidential power and to make decisions that are in the best interests of Americans.

“Giving the president fast-track authority is like giving foreign corporations a blank check to rewrite or avoid US laws,” says Earthjustice managing attorney Martin Wagner. “Without any effective congressional or public influence over the details of new trade agreements, and with no meaningful check on corporate power in using them, these agreements get it backwards, prioritizing the profits of corporations over people and the environment.”

The International Program partners with organizations and communities around the world to establish, strengthen, and enforce national and international legal protections for the environment and public health.