Study Shows Aquifers Threatened by Fracking

Throughout the U.S. oil and gas boom, frackers have countered public concerns about water contamination with the assurance that drilling operations target deposits that sit much deeper than drinking-water aquifers. This picture is not entirely accurate, according to recent research.

This page was published 11 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

Throughout the U.S. oil and gas boom, frackers have countered public concerns about water contamination with the assurance that drilling operations target deposits that sit much deeper than drinking-water aquifers. This picture is not entirely accurate, according to recent research.

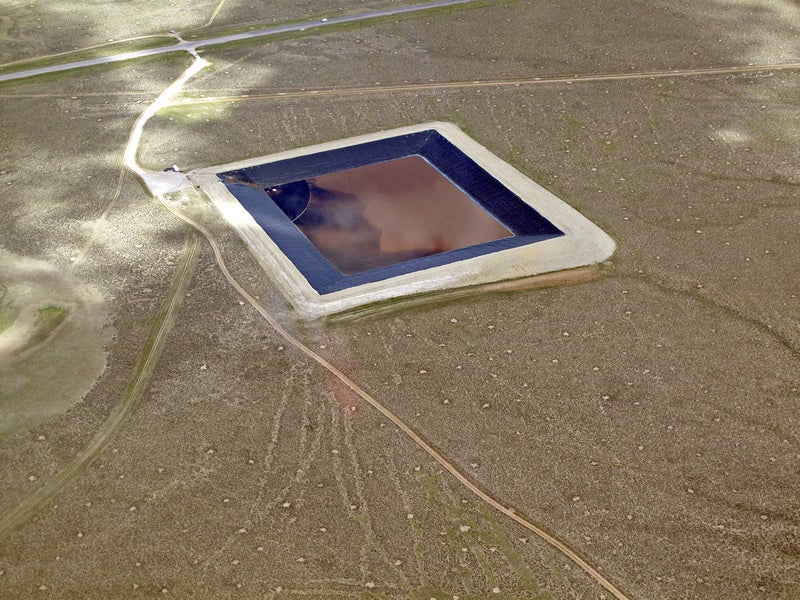

A study presented by Stanford researchers at the American Chemical Society conference last week showed that hydraulic fracturing is employed at two geological formations in Wyoming containing both natural gas reserves and underground sources of drinking water (USDWs). Contrary to industry claims that thousands of feet and layers of impenetrable rock isolate USDWs from drilling and toxic fluid injections, this study found that some of the gas production was occurring at the same depths as the aquifers.

“It's true that fracking often occurs miles below the surface,” said Robert Jackson, one of the scientists presenting last Tuesday. “People don't realize, though, that it's sometimes happening less than a thousand feet underground in sources of drinking water.” According to the study, which is ongoing, companies at the Wyoming sites have used fracking and acid stimulation methods at depths as shallow as 700–750 feet.

For close to a decade, oil and gas companies have enjoyed exemptions from key provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act, allowing the industry to hurtle forward—and downward—with little concern for documentation or disclosure. The Stanford study adds to a mounting pile of evidence suggesting that the lack of regulation is unacceptable: it enables companies to simply say one thing and do another, without consequence. All the while, more and more communities near drilling sites are experiencing disproportionate illness and death.

In absence of adequate EPA regulation, we were left to take industry at their word. But their word is definitively not good enough anymore, if it ever was.