Chickaloon Native Village in Alaska Fights for Its Future

A coal mine threatens the tribe's traditional way of life.

This page was published 8 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

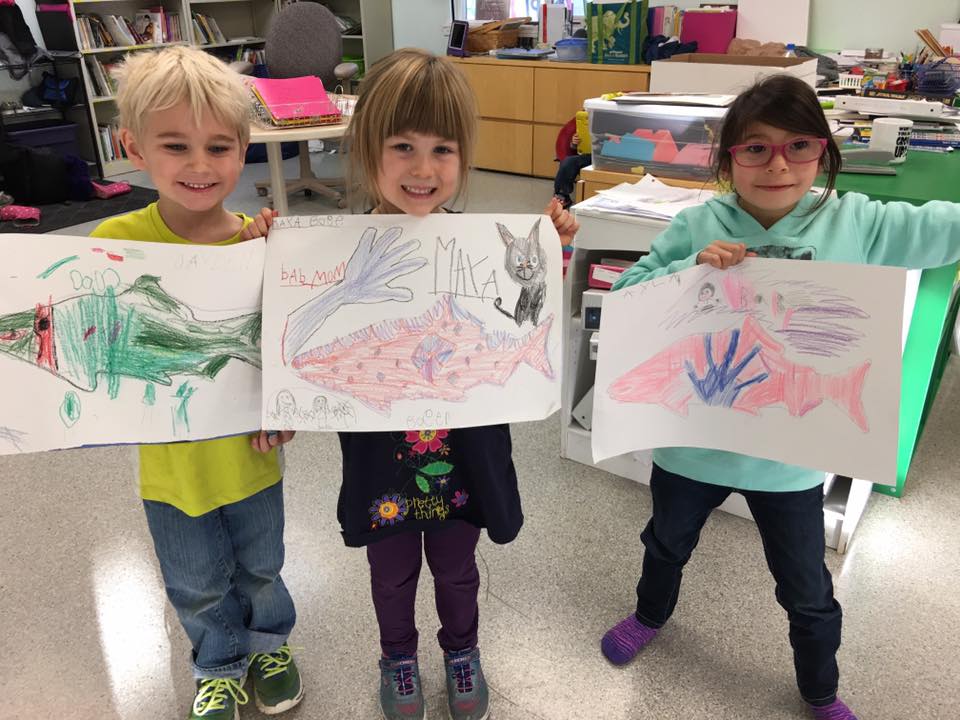

The Ya Ne Dah Ah School is the heart and soul of the Chickaloon Native Village in Alaska. One of the first, and only, schools in the state that is owned and operated by a federally-recognized tribal government, the school excels at teaching tribal youth the skills they need to succeed in the world outside the village, as well as the cultural traditions and Ahtna language that sustain their indigenous identity.

“That language is like medicine,” said Lisa Wade, a member of the Chickaloon Village Traditional Council who also works for the tribal government and at the school. “Each word is healing a part of myself.”

Today the future of the Ya Ne Dah Ah School is under threat. The Wishbone Hill coal mine, which sits directly across from the school, was granted a permit to operate in 1990 but lay dormant for two decades. Beginning in 2010, Usibelli Mining Company launched efforts to commence mining operations. They clear-cut row after row of trees and began building a road that runs almost directly across from the school. The road currently sits unused in the middle of a sacred area, bisected by Moose Creek, where Chickaloon Native Village tribal citizens have gathered food, hunted and fished for generations.

If the federal government’s Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSM) allows Usibelli to continue move forward, the future of the school – and this sacred area – is at stake.

“As Ahtna people, we take stewardship of our environment very seriously. It is our responsibility to the future generations. Ensuring resources are here for the future is vital,” said Gary Harrison, traditional chief of the Chickaloon Native Village. “Usibelli’s mining operation will impact the future of our children and their ability to live healthily off this land. This is unconscionable.”

Photo courtesy of Lisa Wade

Chickaloon Native Village, represented by Earthjustice, has been working with other local groups to keep the mine closed.

“We just want to do what we’ve always done,” said Shawna Larson, a member of the tribal council who first approached Earthjustice about taking their case. “We’re fighting for our way of life – for who we’ve always been.”

The Chickaloon Native Village has been in this fight before. They understand exactly how coal mining will impact their way of life.

For centuries, Moose Creek had been known as “Tsidek’ etna’” or “Grandmother’s Place Creek,” because it was a place where grandmothers and families could safely harvest fish – including all five species of Alaskan salmon.

Beginning in 1923, the coal industry rerouted Moose Creek to construct a railroad spur to transport coal from nearby mines. Over several decades, the industry altered the creek – several waterfalls were created and the creek’s natural winding curve was straightened, eventually making it impassable to spawning salmon.

As a result, the creek’s salmon population was decimated and members of the tribe had to travel great distances to harvest the salmon they had always relied on for sustenance. With the loss of their traditional food source came the loss of language and other cultural traditions.

In addition, coal mining brought with it outsiders – who introduced alcohol, foreign diseases and violence against tribal citizens. Together with the loss of their traditional food sources, these problems had dire impacts for the Chickaloon Native Village tribe – families were torn apart, ancestral language and cultural traditions were no longer passed down to the next generation.

“Our family experienced a lot of complex trauma in a very compact period of time,” Wade said.

Coal mining continued in the area until after World War II, when coal production decreased dramatically throughout the state. Today, there is only one coal mine operating in Alaska – 150 miles to the north of the Wishbone Hill site – it is owned and operated by Usibelli Mining Company.

Photo Courtesy of Ground Truth Trekking/CC BY NC 2.0

In the area surrounding Chickaloon Native Village, the scars from mining remain – coal still burns underground in some abandoned mine sites, literally continuing to wound the earth years later.

In the early 2000s, the tribe set about restoring Moose Creek. After several years of planning and securing funding, they began building a flood plain and repairing the channel with in-stream structures for improved and diversified fish habitats.

“On June 14, [2006,] Moose Creek was diverted back into the original channel. Within two hours the new channel was running clear and looked as the creator intended,” writes the tribe’s Department of Environmental Stewardship on its website. “We were very ecstatic about the significant numbers of young salmon.”

In the decade since, the tribe has resumed many of the cultural activities that revolve around Moose Creek. Culture camps, have been held in the winter and summer – tribal members gather to live communally in tents for a week, and teach the younger generation how to live off the land. They learn everything from how to cook with birch baskets and jar salmon for the elders to how to hunt safely with a bow and arrow and scrape hair off moose hide to make clothing or drums.

“People fall into their roles and responsibilities, and our communal way of living together deepens,” Wade said. “It’s part of our healing journey. We feel better – stronger and more connected.”

Photo Courtesy Chickaloon Village Traditional Council

At the same time, the school has been thriving. A new wing was recently completed and enrollment numbers are at their highest. But all that could change if Usibelli Mining Company has its way.

“I don’t know how many people are going to want to stick around and send their kids to a school where a mine is across the street,” Larson said. “They wouldn’t do that with any other school.”

Since Usibelli started building the mine access road seven years ago, the tribe has been fighting the mine in court, represented by Earthjustice attorney Tom Waldo.

“I don’t know how many people are going to want to stick around and send their kids to a school where a mine is across the street.”

“Earthjustice has stuck by us and helped us,” said Larson. “Earthjustice has represented us from a tribal standpoint rather than just an environmental standpoint. The tribe’s been fighting for our sovereignty.”

Last summer, a federal judge ruled that OSM misapplied federal law in failing to halt initial operations at the mine.

Usibelli’s permit to operate the mine was issued by the state of Alaska in 1991. According to federal law, if mining operations fail to begin within three years of the permit’s issue date, a new permit must be obtained. This helps ensure that mines are operated only under up-to-date permits.

The judge ordered OSM to make a decision about the permit that complies with federal law. In the months since, presidential politics have come into play.

At the end of the Obama administration, OSM issued a decision that effectively required the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to invalidate the permit. In response, the state asked OSM to conduct an informal review of that decision – a review that has since been ongoing. Meanwhile, the Trump administration announced a nominee to head up OSM in October: Steven Gardner, a coal industry consultant from Kentucky who has strong support from the mining industry.

And then, on December 14, OSM issued a decision that dodged the problem, punting it back to the same state agency that has repeatedly refused to apply the plain language of the law.

Michael Penn for Earthjustice

“It is disappointing that OSM ducked the problem,” said Waldo. “But the court’s decision does not leave any wiggle room: DNR must terminate the permit. We will be watching closely.”

In Chickaloon Native Village, tribal members are trying to move forward with their lives despite the looming threat. The constant fight has worn on many of them.

“In order to heal our families from the destruction, we are living our way of life,” Wade said. “Sometimes that’s hard to do that when you’re also attending to all the things coming at you.”

Larson has spent so much time over the past several years traveling to raise awareness about the tribe’s plight, she estimates that she missed out on three years of her daughter’s life.

“Constantly fighting, fighting, fighting – it burns you out,” she said. “Fighting for your way of life, fighting to just be who you are.”

If OSM deems the Wishbone Hill permit invalid, there is a chance that Usibelli could apply for a new permit. For the Chickaloon Native Village, that means the fight would begin all over again. At the same time, the mining company would be forced to go through a new review process, subjecting a 27-year-old permit for a mine that has never been opened to the latest scientific advancements as well as fresh eyes.

“It feels like we don’t matter, they’re stepping over us like we don’t exist,” said Kari Shaginoff, a member of the tribal council who moved back to the Chickaloon Native Village so that her children could attend Ya Ne Dah School and learn the language and traditions that she missed out on growing up. “They’re mindful that we use that land and it’s a part of us but they’ve decided they’re going to do it without listening to us. It feels like we’re inhuman to them, we’re not worthy enough in their minds.”

Waldo is hopeful that since the Wishbone Hill coal would be used for export, the falling price of coal internationally could motivate Usibelli to walk away from the mine.

Either way, Earthjustice is in it for the long haul, says Waldo.

“This is a native community that occupied and governed this area long before European settlers, and they are the ones most directly affected. They deserve a voice in the fight,” he said. “I’m honored to help provide that voice in court.”

In the meantime, if the Chickaloon Native Village could send one message to Usibelli, it would be this, according to Shaginoff.

“You are not welcome here. The school is the heart of our community, our tribe. Our kids – their health, well-being, education – are our top priority.”

Opened in 1978, our Alaska regional office works to safeguard public lands, waters, and wildlife from destructive oil and gas drilling, mining, and logging, and to protect the region's marine and coastal ecosystems.