An Oil Company Planned to Bulldoze Black History. This Community Fought Back.

A sprawling oil complex could have desecrated the remains of Ironton’s founders and poisoned their living descendants with toxic emissions.

This page was published 3 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

Everyone in Ironton knew about the bones at St. Rosalie.

The 200-acre plot in Louisiana, where oak trees spread a canopy over wafting grasses, was once a sugar plantation where enslaved people labored in the 1800s. Residents of Ironton, where everyone is Black, can trace their roots directly to those people – a rare genealogical feat within the diaspora.

Not everyone treated St. Rosalie with reverence. In 2019, an energy company tried to build a sprawling oil complex on the plot, which could have desecrated the remains of Ironton’s founders and poisoned their living descendants with toxic emissions.

The company tried to hide the worst effects of its plan from Ironton’s residents, state permitters, and anyone who might stop them. Had it succeeded, it would have become the latest act of cultural erasure against Black residents who’ve resisted brutal segregationist leaders, greedy fossil fuel corporations, and countless threats to their existence.

Andrea DeClouet, photographed in Ironton, Louisiana. (L. Kasimu Harris for Earthjustice)

But that’s not how this story ended. The people of Ironton fought for their right to preserve their history – precious evidence of a long line of survivors. They were aided by an Earthjustice attorney who helped expose the project’s hidden impacts by decoding a suspiciously empty phrase, and Louisiana environmental advocates who are fighting the oil industry’s last gasp in the Gulf. And, Ironton advocates say, by the protective spirits of the dead themselves.

“Somebody’s always going to tell a dead man’s tale,” says Andrea DeClouet, who lives in Ironton. “The dead will do that for themselves anyway, especially when you walk up on a relic like that.”

In January of 2020, Earthjustice attorney Mike Brown read a phrase that made no sense.

He was going through an environmental assessment produced by a Kansas-based oil company, Tallgrass Energy, which was pushing to build a 20-million-barrel oil storage facility at a site along the Mississippi River, about 40 minutes south of New Orleans. Building the tank farm involved constructing a new pipeline from Oklahoma to transport fracked oil to the site and creating a colossal port accessible to Very Large Crude Carriers.

The other side of the St. Rosalie site houses a 2,400-acre Phillips 66 oil refinery. An independent contractor hired to assess the project’s emissions made an astonishing calculation: Together, the two facilities would unleash large amounts of benzene, a deadly carcinogen, over the people of Ironton.

“You have all these interlocking air pollution issues,” says Brown. “Folks in Ironton would suffer excessive levels of cancer risk just from that one pollutant.” To add insult to injury, the project would also have threatened efforts to restore coastal wetlands and made the community even more vulnerable to spills during climate-change-intensified hurricanes.

“This project was wrong on so many levels,” Brown says.

Representing the Sierra Club and Healthy Gulf, who were aiding Ironton residents in challenging Tallgrass, Brown and his team prepared an argument using the Clean Air Act that contested Tallgrass’s “creative science,” which falsely lowered the terminal’s projected emissions.

As he went through Tallgrass’s assessment, Brown remembers, he found that “in typical fashion, the company filed this very boilerplate document that talked around every issue – including these vague references to ‘cultural resources.’”

The phrase raised an immediate red flag in Brown’s head.

The oil and gas industry survives on three things: the sacrifice of marginalized people, the complicity of politicians, and the legal cloak of empty statements. Brown made some records requests and discovered what was really going on: Tallgrass had uncovered two unmarked cemeteries with human remains and over 12,000 artifacts likely belonging to enslaved people – whose descendants lived across the oaks in Ironton.

The people of Ironton have resisted attempts to erase their existence for over a century.

In the late 1800s, people who were emancipated from the St. Rosalie sugar plantation settled in a nearby woodland and built the community of Ironton. Others arrived from nearby plantations, making Ironton one of the most important settlements of formerly enslaved people west of the Mississippi. Spanning four blocks connected by a forking dirt road, Ironton grew into a tightknit Black haven, forged through shared history and a determination to thrive through adversity.

“Ironton was full of people, homes, children running,” says Pearl Sylve, a lifelong resident of Ironton who is now in her 80s. Her father was among the last generation of people who labored at St. Rosalie before making a new life in Ironton. “Peaceful. People always greeted each other. As a child, I’d go out on the levee and slide up and down on a pasteboard box with my siblings.”

DeClouet, who works at a library in the neighboring town of Belle Chasse, is a history lover. She has spent many hot afternoons on the porches of Ironton’s elders listening to their stories. The town’s history, she summarizes, is one of self-sufficiency.

“Our founders were freemen who bought this property with whatever money they earned and saved,” recounts DeClouet. “They established Ironton for themselves, built their own homes, had their own businesses. They had their own midwives to birth the babies.”

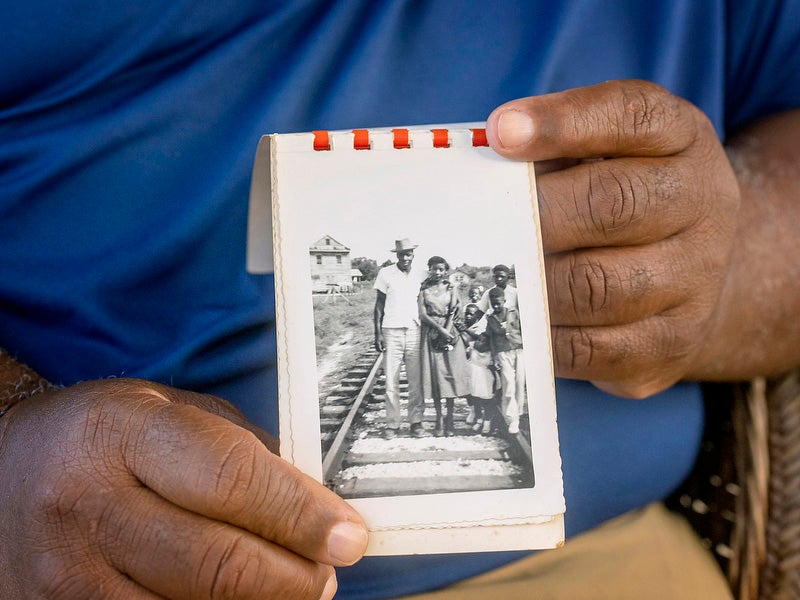

Ironton resident Wilkie DeClouet, the husband of Andrea, holds a family photograph. (L. Kasimu Harris for Earthjustice)

Ironton persisted through decades of brutal segregation. From the 1920s through the 1960s, Plaquemines Parish, where Ironton is an unincorporated community, was controlled by Leander Perez, an infamously racist political boss and oil tycoon. As district attorney and council president, Perez passed laws to keep schools segregated, engaged in voter suppression, fraudulently pocketed millions of the state’s oil royalties, and even tried to imprison a Black teenager without a jury trial for touching a white teenager.

As a Black town in a mostly white parish, Ironton has long been targeted for the oil industry’s heaviest-polluting projects. It is surrounded by the 2,400-acre Phillips 66 Alliance oil refinery, a grain terminal, and two coal export terminals that fling coal dust onto residents’ homes and send petcoke debris the size of a fist floating down the Mississippi. In 2015, locals prevented a third coal export terminal from being built near Ironton. Tallgrass’s facility would have fit into a century-old narrative of environmental exploitation.

Houses in Ironton, photographed in July 2022. (Alison Cagle / Earthjustice)

When DeClouet tried searching the library’s archives for records of Ironton during Perez’s reign, there were virtually none.

“The periodicals, magazines, newspaper articles – everything was white,” she recalls. “That shook me to the core. I came home from work to my husband nearly in tears. I said: It’s like Black people never had a beginning in this parish until this man died.”

Black Americans’ exclusion and excision from documented history has spanned centuries, with terrible consequences. The erasure of genealogical records was a key tool for enslavement. Even before making the deadly Atlantic crossing, African families abducted from their homelands were purposefully separated and their tribal affiliations broken, to emotionally dislocate individuals who might otherwise unite against their oppressors.

In the face of such historic erasure, the survival of Black towns like Ironton, whose inhabitants can trace their lineage back nearly two centuries, is an audacious victory for the preservation of Black cultural memory. The relics at St. Rosalie are a rare genealogical treasure – making Tallgrass’s obfuscation an insult that is deeply rooted in supremacist oppression.

Mike Brown and a community advocate from Healthy Gulf, Michael Esealuka, shared Tallgrass’s discovery with Ironton residents at the town church. People were outraged and disgusted, though not surprised.

“It was another slap in the face for them,” Esealuka recalls from the meetings. “Slavery set us up for a plantation economy, and some areas of Louisiana are still operating in that mindset. Oil companies are building factories in the same plots where the plantations were.”

While Esealuka gathered public comments and Brown fought Tallgrass in the court of law, Ironton residents skewered Tallgrass in the court of public opinion. They vocally denounced the project to New Orleans–based media and called out parish leaders who supported it. Local officials began backing out, claiming that Tallgrass and the port had hidden the discovery of the burial sites in bad faith.

Earthjustice attorney Mike Brown. (L. Kasimu Harris for Earthjustice)

Tallgrass relentlessly pushed ahead with its air permit application, key to the project’s approval, but gave assurances that now it would respect the burial site. Ironton residents weren’t having it, and Brown got ready to appeal the state’s expected approval of the project.

Amid the fight in the summer of 2021, disaster struck Louisiana. Hurricane Ida smashed ashore and obliterated over half the homes in Ironton. The storm surge flooded the streets, upending any building that wasn’t elevated. Caskets rose from the oversaturated ground and ended up in people’s driveways. After the hurricane, Earthjustice attorneys joined Healthy Gulf volunteers to gut Ironton’s church, where the original 1870s floorboards had rotted away. Physical records of Ironton’s milestones – births, deaths, marriages – were lost.

A few months later, Tallgrass withdrew its permit application. The company cited environmental concerns and cultural considerations. In the words of Ms. Pearl: “It was too hard for them to deal with the Black people in the end. We stood up for our rights.”

Andrea DeClouet looks over the sanctuary of Saint Paul Missionary Baptist Church in Ironton, which was damaged by Hurricane Ida in 2021. (L. Kasimu Harris for Earthjustice)

When asked why they chose to fight the oil terminal, Ironton residents say they had to protect not just their health and homes, but also their right to thrive within a society rooted in oppression.

“All of us are close,” says Nadine Black, a nurse. She is one of less than a dozen residents left in Ironton; everyone else was forced to flee after the hurricane. Nearly a year later, residents are still waiting for the government to provide emergency funds to rebuild the town.

“We family; that’s how it is,” Black says. “We built this community for ourselves. Why am I going to leave?”

Ironton resident Nadine Black. (L. Kasimu Harris for Earthjustice)

Earthjustice’s Fossil Fuels Program is taking on the fossil fuel industry’s efforts to pursue new paths to profit that not only accelerate the climate crisis, but also continue to cause harm to marginalized communities.