Growing crops for fuel is not a climate solution. Sustainable agricultural practices aren’t going to change that.

Earthjustice and partners urge USDA to consider the full climate impact of crop-based biofuels when evaluating the potential benefits of using sustainable growing practices for biofuel production

Sustainable agricultural practices like reduced tillage, buffer strips, improved nutrient management, and cover crops can help reduce agriculture’s sizeable greenhouse gas footprint while also improving water and air quality, restoring soil, and building climate resiliency. However, using these practices will not offset the environmental harms and climate costs that come from using tens of millions of acres of land to grow crops to produce biofuels, and these practices should not be used as justification to expand reliance on this false solution to reduce transportation emissions.

This was the overriding message in comments that Earthjustice and partners submitted in July to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) on how to quantify, report, and verify the effect that climate-smart farming practices have on the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with growing crops to produce biofuels.

Crop-based biofuels — primarily corn grown for ethanol and soy grown for biodiesel — have a devastating impact on the climate and the environment. As demand for these crops to produce biofuels rises, land is converted from grasslands and forests to cropland, resulting in large losses of previously stored carbon and reductions in carbon sequestration. (This land conversion can be either in the U.S. or, because we have a globally interconnected agricultural and food system, in other countries.) Growing biofuel crops such as corn also requires intense nitrogen fertilization — most of which runs off into surface or ground water or is converted into nitrous oxide — a GHG approximately 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Indeed, increased biofuel emissions from nitrogen fertilization alone can completely negate any emissions savings from reduced fossil fuel usage. Increased crop production for biofuels also increases air, water, and soil pollution and threatens wildlife.

Critically, it’s not just the year-to-year new conversion of land here or abroad that harms the climate. Using land to grow crops for biofuels also means that this land cannot be used for other purposes, including sequestering carbon in grassland or forest land or producing food — responding to the worldwide increase in demand. The carbon sequestration that would occur under restored natural vegetation instead of agricultural land use is also known as its “carbon opportunity cost” (COC).

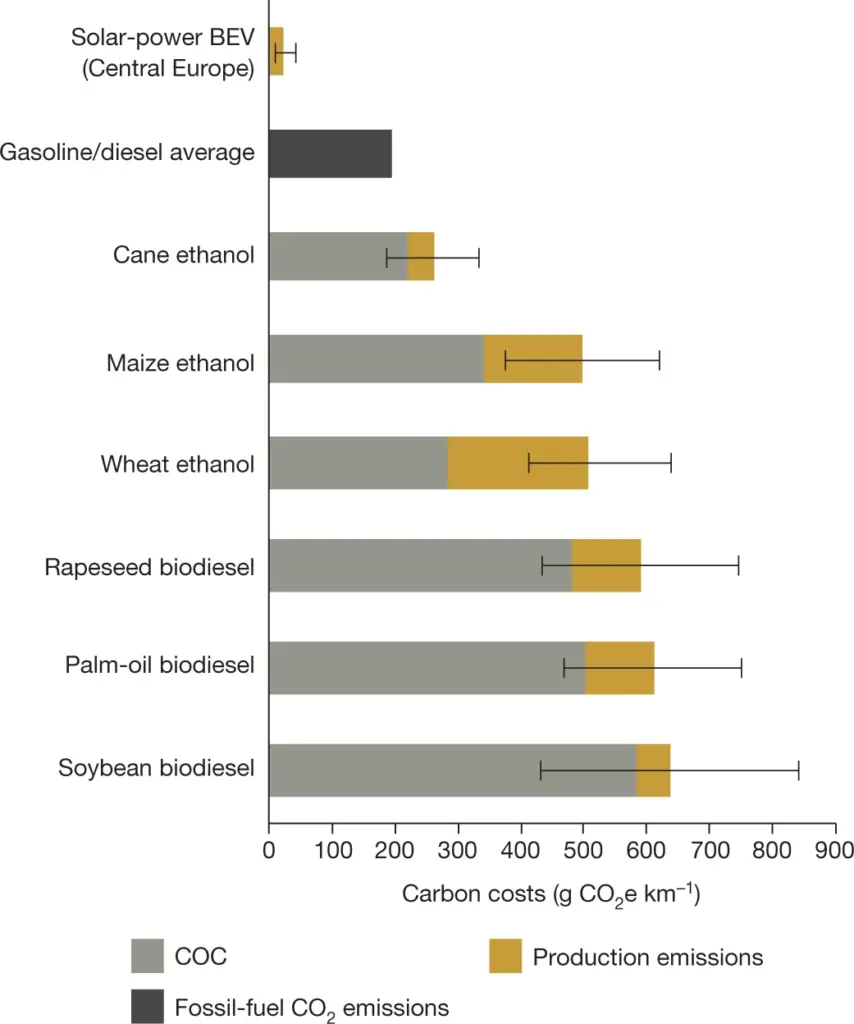

Well-established science solidly recognizes this COC impact of agricultural activities (examples here, here, and here). However, biofuel advocates vehemently oppose it because when COC is factored into a lifecycle GHG emissions analysis, the climate impact of corn and soy-based biofuels is two to three times higher than gasoline or diesel fuel.

The carbon costs of different fuel sources (per kilometer driven). Timothy D. Searchinger et al., Assessing the Efficiency of Changes in Land Use for Mitigating Climate Change, 564 Nature 249, 251 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0757-z

Instead of using sustainable practices to make crop-based biofuels marginally less destructive, clean transportation policy should focus on decarbonization. Electric vehicles powered by a clean electricity system can achieve truly zero carbon road transportation without the unacceptable environmental and land-use harms of biofuels from crops. Solar panels are much more efficient at converting sunlight into energy than corn is, and as a result, solar panels require less land to generate the same amount of energy as ethanol from corn or diesel from soy. The efficiency gap between solar and biofuels widens further at the gas pump, where biofuels are used to power combustion engines that are far more inefficient than electric engines. In our comments we cite a study that shows that an acre of land used for solar energy to power electric vehicles will deliver 200 – 300 times as much mobility as an acre of land used to grow corn for ethanol. Obviously, the size of this advantage varies based on which areas are compared — some places are better for solar or corn production than other areas. However, even estimates based on Iowa data (great for corn, less so for solar), still find solar to be 70 times more efficient than corn ethanol. Even including the energy in biomass byproducts that are not used in biofuel production, solar has a huge land edge over biofuels.

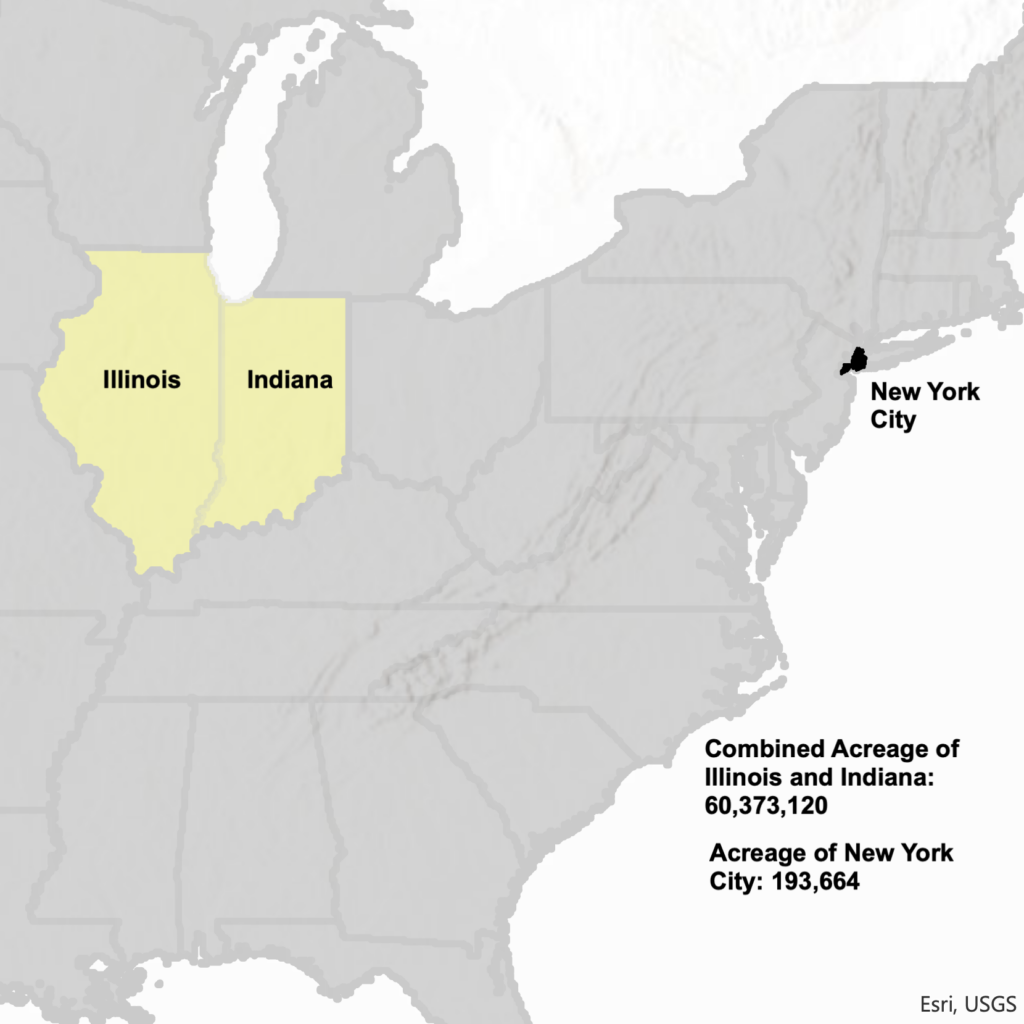

To put this in perspective: today, nearly 60 million acres are used to grow corn and soy for biofuels — equivalent to about all the land in Illinois and Indiana combined. If solar is 300 times more land efficient than corn ethanol, about 200,000 acres of solar panels — roughly the size of New York City — would provide the same transportation energy. (See figure below.) This would leave over 59 million acres to help us drawdown carbon and stabilize the climate or to feed people.

Today, nearly 60 million acres are used to grow corn and soy for biofuels – equivalent to about all the land in Illinois and Indiana combined.

For hard to electrify transportation, including aviation, biofuels made from food, crop, and other waste, which do not require the dedicated use of land, could play a role. And, just as land vehicle electric technology advanced far more rapidly than expected when the Renewabl Fuels Standard was enacted, so might options for aviation. We should not lock ourselves into bad technology in hopes of solving a problem.

Sustainable practices can help reduce agriculture’s climate footprint, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) should continue to research and support the adoption of climate-friendly practices on agricultural lands. Earthjustice and our partners strongly support the provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act that provide more funds to farmers to adopt these programs and are urging Congress to continue this extra funding in the next Farm Bill. Farmers want to implement these practices now but two out of three farmers that apply for conservation funding through Farm Bill programs are turned away for lack of funds. But while these practices can help reduce the impact of crops we need to grow to survive — our food — they cannot convert a Rube Goldberg fuel source into a climate solution. We urge USDA to weigh the climate and environmental impacts of crop-based biofuel production as whole, including the carbon opportunity cost, in addition to considering the benefits of individual farming practices. Improvements at the margins through sustainable farming practices are not enough to make crop-based biofuels a climate-smart path forward.

Earthjustice’s Sustainable Food and Farming program aims to make our nation’s food system safer and more climate friendly.