‘Conflicts Checks’ and Biden’s Judicial Appointees

Will Biden follow through on his promise to rebalance the federal bench? Here’s what to watch for.

A lot is different this summer, but one thing remains the same: our annual reminder, as the Supreme Court releases the final opinions of its term with the dramatic timing of a fireworks technician, of the vital role the courts play not just in our tripartite federal government, but also in the places where we work, study, live, and play.

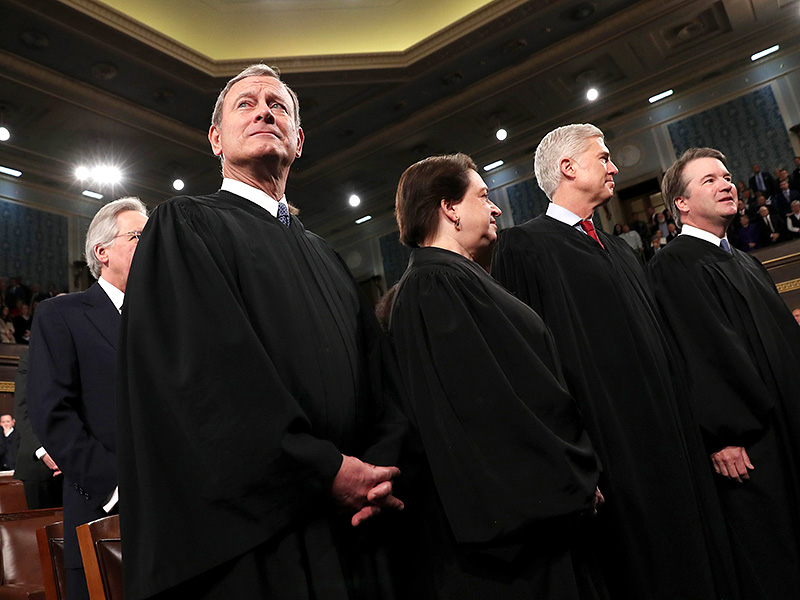

By “courts,” I mean judges. And if, like Chief Justice John Roberts, you think that judges simply call balls and strikes, you haven’t been paying attention to the GOP’s almost fanatical commitment to appointing federal judges over the last three and a half years. “Trump judges” now occupy a quarter of the federal bench.

As an environmental litigator, I am less interested in who appointed them than in who they worked for before becoming a judge — and who they didn’t work for.

[W]hen you spend decades arguing for one side, it’s likely to affect your judicial philosophy.

I was fortunate to clerk for judges in U.S. District and Circuit Courts and then on the Supreme Court. While I don’t agree with Chief Justice Roberts’ “balls and strikes” analogy, I do agree with him that most judges are independent thinkers. In my experience, they don’t consider the views of the president who appointed them when they make their decisions.

But I also know that judges are human, and that their perceptions — from whether a witness is credible to whether a justification is reasonable — are shaped by their life experiences. A few years ago, for example, researchers from Harvard and Emory looked at thousands of decisions and found that among male judges, a statistically significant predictor of how they ruled in gender equity cases was the simple fact of whether they had a daughter.

Excerpt from “Identifying Judicial Empathy: Does Having Daughters Cause Judges to Rule for Women’s Issues?” (2014)

American Journal of Political Science

It’s not hard to extend this inference to corporate law. Lawyers who have spent most of their careers representing corporations are more likely to be sympathetic to the views of such companies — and particularly their view that government regulation, licensing, and permitting is a pain in the neck.

If true, this is quite troubling for those of us who rely on courts as a check on the power of corporate polluters. That’s because, for decades, Democratic and Republican administrations alike have shown a strong preference for judicial nominees who have spent significant time in service of corporate America. One reason is that it’s hard to become an influential political donor on a nonprofit or government salary.

The group Demand Justice recently found that nearly 60% of sitting appellate judges were previously partners at large law firms, meaning that they spent at least a decade of their legal careers — and often far more — advancing the interests of corporate clients that can pay four-figure hourly rates.

Source: “Jobs, Judges, and Justice: The Relationship between Professional Diversity and Judicial Decisions” (2021)

Demand Justice

This doesn’t mean these judges are unqualified — far from it — but when you spend decades arguing for one side, it’s likely to affect your judicial philosophy.

It’s true that corporate lawyers can gain perspective through their pro bono service. And many do volunteer their time to represent criminal defendants, social justice organizations, and other folks who can’t afford a lawyer.

But the frustrating truth is that virtually none of them ever represent a community, tribe, or non-governmental organization that needs pro bono environmental representation. Here’s why: Their firms won’t let them.

Before a lawyer at a firm can represent someone, pro bono or otherwise, the firm must perform a “conflicts check” to ensure that the representation wouldn’t put the firm crossways with any of its other clients — even if those clients aren’t involved in the case. This is an ethical requirement, and it’s good business too: Your paying clients may walk out the door if they find that you are doing free work for the other team. And the vast majority of big law firms have at least one Big Oil, Big Ag, Big Coal, or Big Chemical client that would prefer that the firm not take on a pro bono case challenging a pipeline, timber sale, toxic pesticide, or oil lease.

I can’t tell you how many times a friend at a big firm has called me up excited to defend a wilderness or represent an overburdened community they’ve heard about in the media. But I can tell you how many times that offer has panned out: never.

One of the things that heartens me about President Biden’s judicial nominees is that many of them have spent significant portions of their careers serving clients who aren’t corporations, and at legal organizations that don’t have any polluters as clients.

Watch closely in the coming weeks and look at the backgrounds of Biden’s judicial appointees. Let’s see if he really follows through on his promise to rebalance the federal bench by seating judges with truly diverse legal experiences — and let’s see how hard Mitch McConnell fights against it.

Earthjustice’s Washington, D.C., office works at the federal level to prevent air and water pollution, combat climate change, and protect natural areas. We also work with communities in the Mid-Atlantic region and elsewhere to address severe local environmental health problems, including exposures to dangerous air contaminants in toxic hot spots, sewage backups and overflows, chemical disasters, and contamination of drinking water. The D.C. office has been in operation since 1978.

Lauren Wollack

Vice President, Public Affairs and Communications, Earthjustice

lwollack@earthjustice.org