Earthjustice stands with western Alaska tribes and families after severe storms devastated entire communities, displacing more than 1,000 residents just before winter. Learn more and how you can help.

June 4, 2025

Mining Makes No Sense to the Southwest Alaska Tribes Challenging the Donlin Gold Mine

Alaska Native tribal leaders explain how a massive gold mine proposed in their region poses grave risks to villages, food security and continued tribal traditions

Scenes from the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta: Caribou lichen and alpine azaleas are part of the intricate tundra plant life. (Diane McEachern) Fishing skiffs tied up on the riverbank along the Kuskokwim River in the village of Akiachak. (Design Pics Inc / Alamy) Preparing and preserving salmon. (Rachel Ruston / Northern Center)

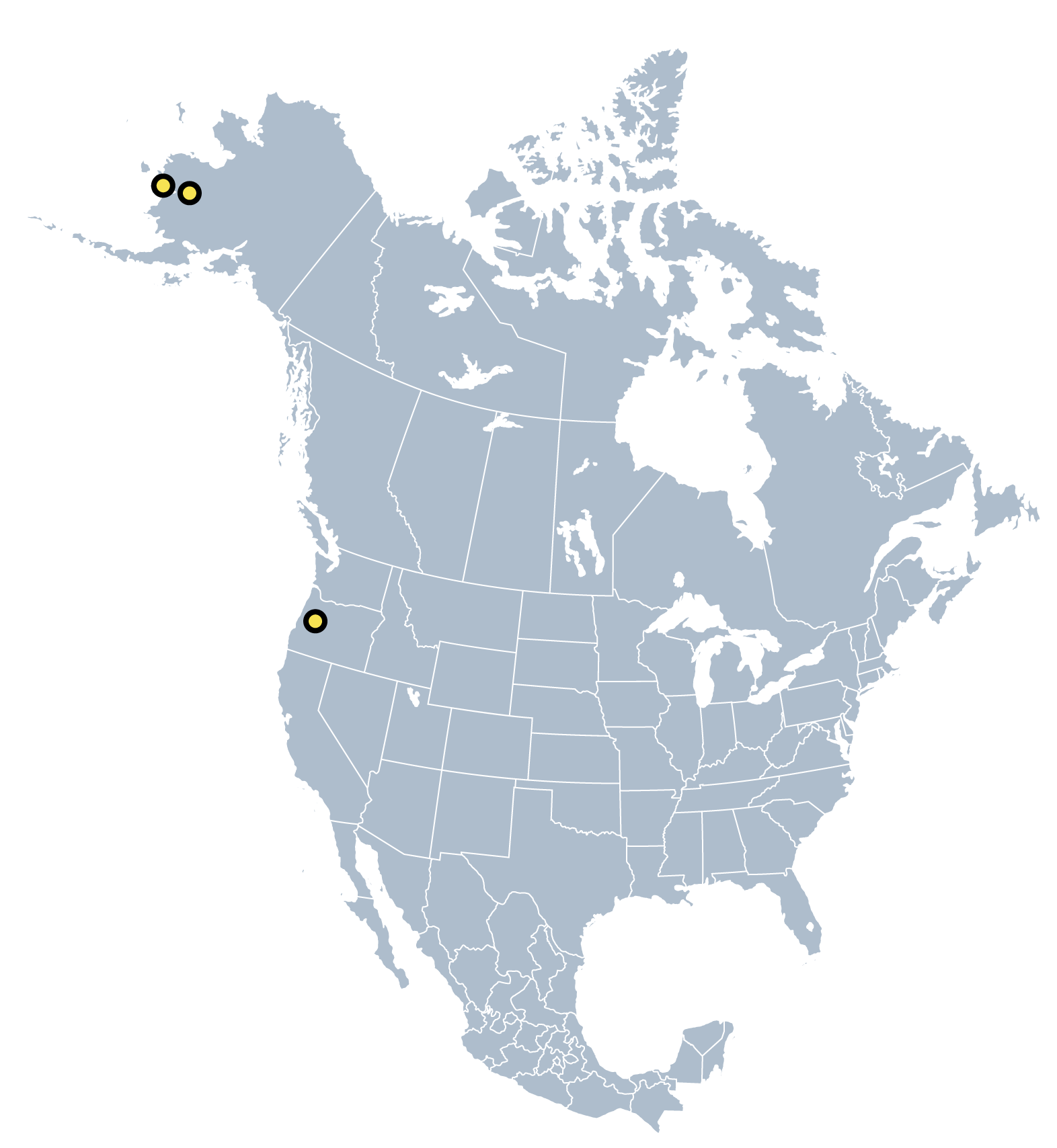

In late February, three Alaska Native leaders traveled thousands of miles from snowy Southwest Alaska to Eugene, Oregon, to present alongside Earthjustice attorneys at the Public Interest Environmental Law Conference (PIELC).

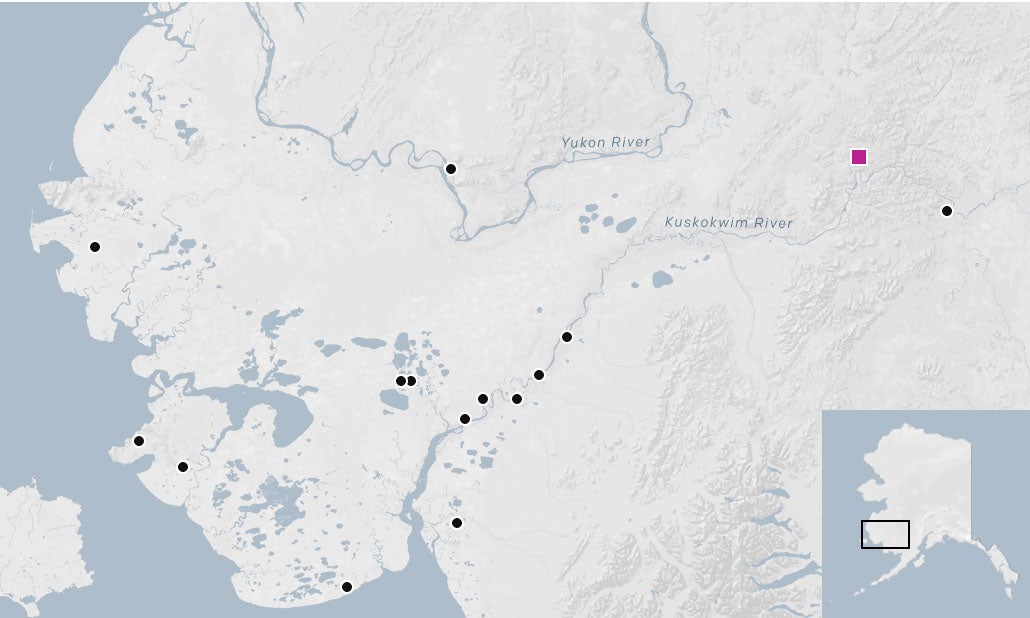

There, they spoke out against the proposed Donlin Gold Mine, a massive project planned in their region near the Kuskokwim River.

If built, Donlin Mine would reportedly be the largest gold mine in the world, producing about 30 million ounces of gold over the 27-year-life of the mine. It would also, Alaska Native leaders say, pose an existential threat to their Tribes’ food security and cultural traditions.

Kwigillingok, AK

Bethel, AK

Eugene, OR

The trip down to the conference took two full days and four flights for William Igkurak, Council President of the Native Village of Kwigillingok. His village, home to fewer than 500 people, is located on the Bering Sea coast near the mouth of the Kuskokwim River.

The trip for the other two Alaska Native leaders, Walter Jim, Jr., Chair of the Orutsararmiut Native Council (ONC), and Ray Watson, an ONC Council Member, also involved multiple flights. Bethel, a village hub with a population of about 6,000 people, is similarly remote, located along the Kuskokwim River about 400 miles west of Anchorage with no roads connecting it to other parts of Alaska.

All three leaders said it was important for them to make the long trip from their villages in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta to talk to a packed room of lawyers, law students, and others because they want people outside of Alaska to understand what their communities stand to lose if the mine project moves forward.

“You can’t eat gold,” Igkurak said during an interview following the presentation.

It sounds like Igkurak is making a joke, but he’s not. As tribal leaders for their communities, protecting subsistence is one of their most serious responsibilities. The three leaders explained that hunting, fishing and gathering wild food means food security and that these subsistence practices form the basis for the whole life and culture of their communities. Gold mining, on the other hand, even if it makes a profit for some, makes no sense in their world view.

“Mining is not even in our culture,” added Watson, a council member of the Bethel tribe Orutsararmiut Native Council (ONC), who over the years has held many different tribal leadership roles. “You’re not supposed to disturb what is there… that makes the ancestors mad.”

Most tribes in the region oppose the project, arguing its long-term risks far outweigh any short-term gains like jobs for some people in the region.

William Igkurak

Council President of the Native Village of Kwigillingok

Walter Jim, Jr.

Chair of the Orutsararmiut Native Council

The tribal leaders say that long after the mine closes, it would pose grave risks to the region’s lands, waters, fish, wildlife and birds — and to tribal members’ subsistence ways of life that have persisted thousands of years and are central to their continued wellbeing.

“Anything manmade is not guaranteed to last,” Igkurak said.

All three tribal leaders talked about how, over time, the mine’s infrastructure would require repairs and could fail. The mine would operate for less than 30 years, a blink of time, while what matters most to them is preserving the lands, waters, and natural resources for future generations.

Also of concern is the tripling of barge traffic expected if the mine is built. Already, the Kuskokwim River’s banks are eroding due to permafrost melting and other changes caused by climate change. More barges on the river will cause even more damage to the river’s banks, threats to fish they depend on, like rainbow smelt, and would make fishing more difficult, they said.

“It’s driven by greed,” said Jim, ONC’s Chair. “Short-term gratification, money. But in the end, it’s the livelihood of our people that is really at the forefront of what we’re doing here” to fight this mine.

Jim said he was born and raised in Bethel, and grew up hunting and fishing, and sharing what he harvested with others. “That’s just something that was passed on to me to make sure, from my elders, who were always telling me, you know, to give and share,” he said.

The 700-mile-long Kuskokwim River is at the center of these subsistence traditions and provides everything to these communities. The river’s waters and nearby lands provide important habitat for fish, birds and wildlife. Before air travel, and continuing today, the river served as the primary way people traveled between villages within the region. In winter, people travel on an ice road on top of the frozen river via cars, trucks, snowmachines or even dog sleds. In summer, people access other villages and fish camps using boats.

When he was younger, everyone was focused on subsistence and people were more able to be self-sufficient. “I used to always see families getting ready for the different seasons, where they hunted or fished or gathered.”

Jim said that while it’s not as prevalent as it used to be, subsistence ways of life where families are “always getting ready” to hunt, fish, and gather are still common in his region. “It’s good to see that,” he added. “You know, it’s good to see that.”

Rainbow smelt, whitefish, and trout are widely fished in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. (Dave Cannon)

Likewise, in Kwigillingok, Igkurak said he grew up with a subsistence lifestyle, first hunting with a slingshot, then a bow and arrow, and then a rifle, which his father taught him to use; he learned to only shoot what he knew he could hit, so as not to injure an animal without killing it, or waste ammunition. Because life has changed and people now need cash incomes to survive, he’s seen a lot of migration out of his village. But for those who have stayed, hunting, fishing and gathering remain extremely important.

“You got to subsist to make ends meet,” Igkurak said, adding that people in the Lower 48 states might complain about paying $3 a gallon for gasoline when it costs close to $9 in his village.

Inside the Legal Case

Tribal governments from the Kuskokwim River region, represented by Earthjustice, are fighting the Donlin Gold mining project.

If the mine is built, the tribal leaders fear toxic chemicals from mining could seep into nearby lands and waters and harm fish, wildlife, and birds, and affect their ability to live off the land.

All three men make the point that all communities in their region depend on the river’s health. People hunt and harvest different resources from different regions — salmon, smelt, burbot, seals, walrus, whales, clams, halibut, ducks, geese, bears, moose, and more. For thousands of years, they have traveled up and down the river, trading what is common in their community for something they can’t harvest locally. That kind of sharing between villages and extended kin is still important to people today, Jim said.

Andreafsky Wilderness

Donlin

Gold Mine

Project Site

Marshall

Sleetmute

Chevak

Yukon Delta

National Wildlife Refuge

Tuluksak

Akiak

Nunapitchuk

Kasigluk

Bering Sea

Bethel

Kwethluk

Napakiak

Tununak

Nightmute

Eek

Nunivak

Island

Kwigillingok

Togiak Wilderness

Area of Detail

Kuskokwim Bay

© Mapbox / © Openstreetmap

“You don’t see any villages located away from the river,” Watson said, “because the river is the lifeline. The resources are there in the river. It’s the gateway to our food, the wood we need for heating, for the life of the people. And that’s the way it’s always been.”

“We’re afraid of the pollution, if the tailings ponds overflow or the dam breaks,” Jim said. “If our river becomes contaminated, we rely on everything that lives in that water. Everything is dependent on that water for life.”

“Whatever flows out of Kuskowim River beaches on our shores, so if mine breaks it will contaminate our waters and shores,” Igkurak said.

If subsistence resources were to vanish, so would these communities, Jim added. “If I can’t be dependent on resources that I’ve always been dependent on my whole life, then I’d have to move away, so I can do that somewhere else.”

Watson added that the Yukon-Kuskokwim region, which consists of 56 villages and is about the size of Oregon, is one of the economically poorest in the nation. But, he says, even though it can seem like a poor country to outsiders, they’re proud of their culture — and for all they have survived.

“We’ve lived through so many traumas in our life,” Watson said, “and we’re still resilient. Still, we fight. We’re that way, that’s what’s instilled in all of us. We fight for our people. We fight for our culture. We fight for our life. In spite of the different outside influences that come in. Bethel is my home, and it’ll always be my home.”

Ray Watson

Member of Orutsararmiut Native Council

Photo portraits by Rebecca Bowe.

Rebecca Bowe reports on the litigation docket of Earthjustice's lands, wildlife, and oceans work.

Elizabeth Manning is Earthjustice’s Public Affairs and Communications Strategist for Alaska and Pacific Northwest environmental issues.

Opened in 1978, our Alaska regional office works to safeguard public lands, waters, and wildlife from destructive oil and gas drilling, mining, and logging, and to protect the region's marine and coastal ecosystems.