March 30, 2023

Strengthening Zoning Regulations on Last-Mile Warehouses

Amending regulations on last-mile warehouses is critical to achieving New York City’s environmental justice and racial equity goals

The e-commerce sector has experienced exponential growth in the last decade, with consumer demand for online goods surging by over 33% between 2019 and 2020 alone.

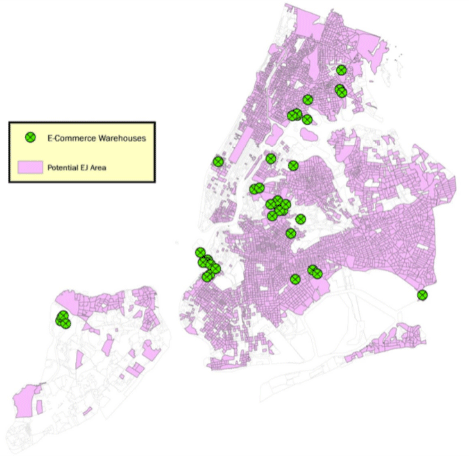

The influx of demand coupled with online retailers’ same- or next-day delivery guarantees has accelerated the buildout of logistical “last-mile” warehouses sited disproportionately within or surrounding lower income communities and communities of color in New York State.

In New York City, last-mile warehouses can currently be built directly adjacent to certain residential neighborhoods, predominantly communities of color and lower-income communities, without any review or mitigation of traffic, public safety, or air quality impacts. The lack of these protections in the City’s Zoning Resolution directly undermines the City’s racial equity and environmental justice goals.

About the Last-Mile Coalition

The Last-Mile Coalition is a city-wide coalition of environmental justice and public health advocates, made up of Earthjustice, The New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, The Point CDC, UPROSE, El Puente, Red Hook Initiative, and New York Lawyers for the Public Interest.

Increased diesel emissions from the uptick in warehouse delivery truck traffic has serious public health impacts, particularly among communities of color and lower-income communities, who already breathe dirtier air than white and affluent New Yorkers.

The Last-Mile Coalition has started the process to amend New York City’s Zoning Resolution to prevent last-mile warehouse facilities from clustering too close to one another in a particular neighborhood, provide communities and City agencies an opportunity to plan for a new facility’s public health and environmental impacts, and give the City authority to require mitigation of negative impacts.

Media Inquiries: Bala Sivaraman, Earthjustice, bsivaraman@earthjustice.org

Established in 2008, Earthjustice’s Northeast Office, located in New York City, is at the forefront of issues at the intersection of energy, environmental health, and social justice.