February 23, 2021

When I was 19 years old, I went to class with a sign hanging from my neck. In thick, black Sharpie it read, “Climate Change Is Real.”

Like many others, I was feeling immense grief over the future of our planet. As I walked across my college campus in Gainesville, Florida, I mostly avoided eye contact with my classmates. I was nervous and embarrassed. (I still kind of am.) But the only thing that seemed more embarrassing than wearing the sign was remaining silent. I wanted to know who else in my community felt as heartbroken as I did. I knew there had to be others, but I didn't know how to find them. So I wore a sign.

Looking back, I see that choosing to wear the sign that day was the culmination of my personal evolution colliding with the events taking place around me. Like many coming-of-age stories, it started with body image. The story I’d been taught — be skinny, be beautiful (implicitly, be White), and you’ll be loved — became demonstrably untrue the more diet sprees I went on. Eating only carrots and celery didn’t make me feel more loved, just taken advantage of.

My belief in the American ethos of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” also began to crumble as I noticed that the people I saw work the hardest around me were paid the least. This included the immigrant custodians who I’d talk to in my mom’s classroom after school, as well as my own mom who took a pay cut to teach at a private school so my brother and I could attend.

Every morning at that same private school, I would pledge allegiance to a flag that promised “justice for all.” Yet I saw Trayvon Martin killed and his killer acquitted just a few hours away from my home. I was beginning to understand that patriarchy, capitalism, and white supremacy — the toxic foundations of our society — were the same forces threatening the well-being of people and the planet.

I knew I wanted to help bring about change. I didn’t yet know I would find salvation in the many other people who do, too.

It turns out I wasn’t the only one looking around and feeling heartbroken by what they saw. There’s a widespread understanding among younger generations that we’ve been dealt an unfair hand; that the planet we’re inheriting is spiraling into something quite terrifying; that we and our children may never enjoy life’s most wonderful places and experiences because climate change, racism, or greed will take them from us.

“It’s no wonder Gen Z is the most stressed generation in America.”

Some call this psychological distress “climate grief” or “eco-anxiety.” I just call it paying attention. And at this particular moment in human history — with mass death, modern day lynchings, tens of millions of jobs lost — paying attention can be devastating. This is especially true for young people, who are graduating into the worst unemployment crisis since the Great Depression and are being particularly hard hit in almost every measure of coronavirus-fueled economic distress.

It’s no wonder Gen Z is the most stressed generation in America.

Fortunately, wearing the climate sign that day in college did eventually lead me to others. My teacher, who turned out to be an environmental activist, connected me with a new, youth-led climate justice organization called the Sunrise Movement

Last February, in what feels like another lifetime, I joined them and other organizers in the movement to knock on doors in New Hampshire’s primary and get young people to vote. My pitch was succinct: “Are you sad about climate change?” “Me, too.” “Vote for Bernie.”

I’ll never forget the night of the New Hampshire primary. Wide-eyed, we stared at projectors showing the results coming in, calculating how many voters we'd contacted vs. Bernie's margin of victory. When it became clear that we had won, that our work had made a difference, we broke into song and dance, laughter and tears.

I know of nothing more life-affirming than a dance floor filled with young people who’ve exhausted themselves in struggle for a worthy cause, who’ve just worked their asses off to change the world. We were a bunch of young, scrappy, grieving kids who came together and transformed our collective grief into something remarkable, into healing. And, for a brief moment, into victory.

Part of what makes this moment particularly challenging is that coronavirus has made it difficult to access the one thing that has kept me grounded and hopeful throughout the years: community.

Nowadays, we aren’t supposed to get within six feet of other people, let alone dance with each other or knock on strangers' doors. But the planet hasn’t stopped cooking just because there’s a pandemic. In fact, the climate crisis and coronavirus are intersecting in disturbing ways that often land heaviest on communities already overburdened by racism, economic exclusion, and environmental degradation.

Despite the challenges of social distancing, I believe there remains no better antidote to despair and hopelessness than finding other people who feel as I do and working alongside them to fix what is breaking our hearts.

My friend Kaith, a community organizer with Dream Defenders, put it well: “Instead of crying, I organize.”

But first, I let myself feel it all. I surrender to the grief. I think of the words of Buddhism scholar Joanna Macy: “If parts of our world that we loved were dying, we would expect to grieve. These feelings are normal, healthy responses. They help us notice what’s going on; they are also what rouses our response.”

I think of the bumper sticker that says, “It’s no sign of good health to be well-adjusted to a sick society.”

I remind myself that the pain I feel for the world is just a reflection of our interconnectedness, of our radical not-aloneness. I make this surrender a part of my daily routine, a regular and expected part of life. For me that has looked like developing a regular meditation practice, letting myself cry, and seeing a therapist. For some of my friends it looks like dancing and taking walks. The common thread is not looking away from pain, but making a habit of looking directly at it. Doing so will likely break your heart. But maybe what the world needs is more broken-hearted people.

Next, I look around and ask myself, “Who else is emotionally destroyed by the state of our world? What are they doing about it? How can I help?”

I ask and answer these questions on a constant basis. Then, in true Zoomer fashion, I follow the helpers on Twitter. I donate to their campaigns. I join their organizations. I volunteer for their projects. I talk to my parents and friends about their work. I help the helpers. Soon enough, I become a helper, too.

It is here in the space of shared grief and shared commitment that I find a way to cope with this ruthless furnace of a world.

Working alongside other broken-hearted people is the most healing practice I know. Broken-hearted helpers are the ones who topple unjust systems and give birth to new ones. We’re what social movements are made of. We’re the ones who change the world.

Postscript

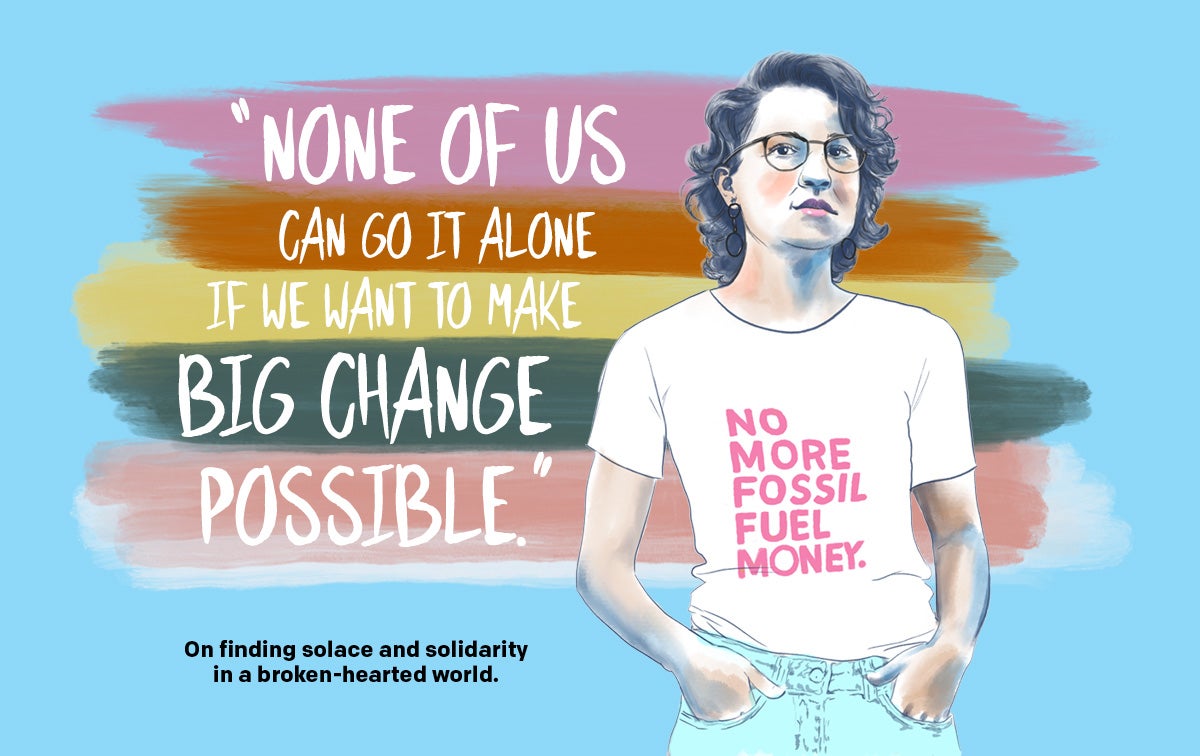

While writing this article, I went back to see if I had any photos of the sign I wore to school, but ended up finding a different photo I had forgotten about. It turns out, that sunny fall day in Florida when I went to school wearing a sign, there was something else I brought with me. Before leaving the house, I took a Sharpie and wrote on my arm the names of all the people whose courage and companionship I wanted to summon to help carry me through my fear. Some of the people I chose I know now are cringey and cancelled — and some are still heroes I admire. Nevertheless, the essence of my intention rings true. I was new to all of this. In many ways I was alone. But I still knew in my gut that I couldn't go it alone. I know now that none of us can.

Marcela Mulholland is the Deputy Director for Climate at Data for Progress and a native Floridian. The views expressed in this piece are hers.

This piece was originally published in August 2020 and updated in February 2021.

About this series

The climate crisis is a product of an unjust system that prioritizes profits above all else. For too long, the fossil fuel industry and its allies have greatly benefitted from this system, often at the expense of our most vulnerable communities.

It’s time to fight for climate solutions that ensure environmental, social, racial, and economic justice for all people. Lit: Stories from the Frontlines of Climate Justice, seeks to highlight these climate justice fights — and inspire others to stand up for their own communities and our shared future.

We know we can’t achieve zero emissions and 100 percent clean energy alone. Join our fight to ensure a more just and equitable world.