Drought Drains California’s Energy Grid

California’s drought is draining the state’s reservoirs and preventing hydropower from feeding the state’s energy grid, creating an opportunity for cleaner energy sources to take its place.

This page was published 10 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

Brown is the new green in California as the state’s historic drought forces residents and policymakers to reevaluate their relationships with water. Dryscaping and succulents are now trendy, I buy almonds with more shame than gossip magazines, and my coworker has a shower timer named “Jerry Brown” in honor of the governor’s water-saving ways. But while many of us are focusing on what we can do to keep the taps from going dry, the state is also working on ways to keep the lights from going out.

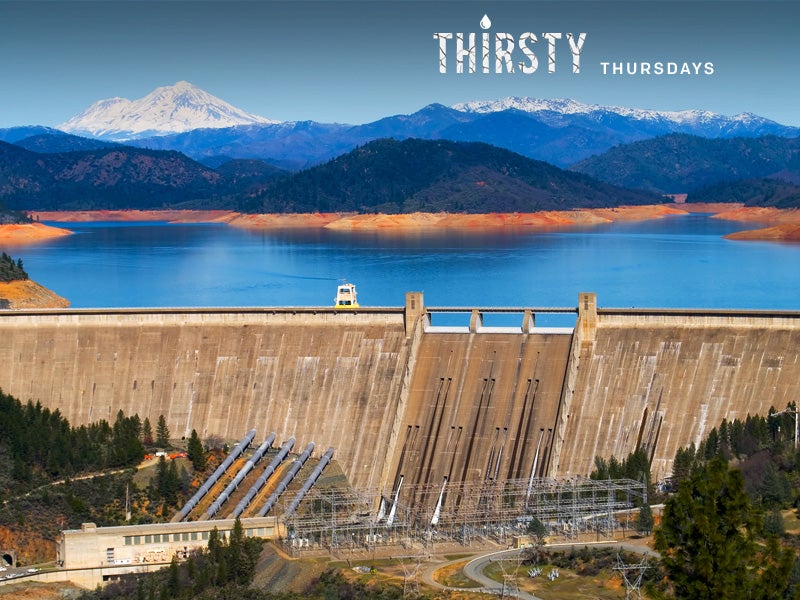

Back in the 1950s, hydropower generated close to 60 percent of the state’s electricity. Over time, that number has slowly declined. In a normal year, hydropower production hovers around 20 percent, drawing from the state’s 300 dams to power homes and businesses. Shasta Dam is one of the state’s largest, and it has lost at least a third of its generating capacity. Last year, California could only squeeze about 8 percent of its power from water.

However, the decline of hydropower as an energy source may not be a bad thing. Yes, really.

Earthjustice doesn’t classify hydropower as a source of clean energy because of the destructive impacts of damming to natural waterways, fish migration and water quality. While hydropower is emissions-free at the point of generation, its entire lifecycle is not. Organic matter like decaying leaves in dam reservoirs can release significant amounts of methane—a greenhouse gas 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide. As a result, the world’s largest dams are responsible for four percent of humans’ total contribution to climate change.

So what’s keeping the generators running?

Right now, fossil fuels are leading the charge. The Pacific Institute reported that increased natural gas usage between 2011 and 2014 cost California ratepayers $1.4 billion and caused an eight percent increase in carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. The study also predicts that these numbers will continue to rise through 2015.

The news that natural gas is king is bad for the environment. But with low reservoirs and Governor Brown’s ambitious goal to run the state on 50 percent renewable energy by 2030, true forms of renewables like solar and wind power have a chance to establish themselves as the future of California’s energy grid. In 2014, wind energy production doubled, contributing eight percent of total energy to the grid. Solar power grew even faster, nearly tripling last year and offsetting 83 percent of the power lost from hydroelectricity. The state hosts more than 250,000 distributed solar projects, which is about half of the total number of projects across the nation. Pacific Gas & Electric is bringing on a new solar system in the state every 11 minutes.

While hydropower is still cheaper than renewables, this kind of rapid growth is a telling sign that there is a place for wind and solar in California’s energy future, but only if we make room for it. As more systems come online, Californians are likely to find that the sun and wind are more reliable than rain to keep the lights on in the decades to come.

About this series

Thirsty Thursdays is a weekly blog series exploring the historic drought in the western United States. In the ongoing series, we’ll share expert opinions, breaking news, compelling articles and the work Earthjustice is doing to protect water resources in a time of extreme water scarcity.

Don’t miss last week’s post: “It’s Time to Be Drought Intolerant.”