A Tribe Takes on Coal

The Northern Cheyenne have a long history of defending their land. Now, they're showing how clean energy progress can still be made.

The Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation spans 444,000 acres of rolling plains, ponderosa pines, and rivers winding through deep valleys in southeastern Montana.

Above it all towers the smokestacks of one of the largest and dirtiest coal power plants in the country: the Colstrip Steam Electric Station. The Tribe’s reservation lies in the middle of the Powder River Basin, the largest coal-producing region in the United States. More than 43% of all coal mined in the U.S. comes from the region. Coal has also historically provided most of Montana’s energy.

For decades, the Tribe has successfully fought to keep coal development off the reservation. However, the coal industry has made its mark on the neighboring land — and its pollution pays no heed to boundaries drawn on a map. For almost a decade, Earthjustice has worked alongside the Tribe in fights against the strip mines and coal power plants next door.

The Tribe celebrated in 2024 when the Interior Department halted new coal leasing in the region, citing dwindling demand and the growing climate crisis. But President Trump and his allies in Congress are determined to prop up this declining industry by undoing the ban and expanding coal’s footprint. Earthjustice and the Northern Cheyenne are prepared to fight back.

Lightning strikes in the distance beyond the power plant in Colstrip, Montana in July, 2025. (Louise Johns for Earthjustice)

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe’s traditional homelands include the Powder River Basin in southeastern Montana and eastern Wyoming, which they inhabited before colonial contact, and fought to protect ever since.

“We are part of the land. We think of ourselves as part of our whole environment. Not just the land, but with the animals, the water, the air, everything,” explains Charlene Alden, the Tribal Environmental Protection Director. “It’s what keeps us alive. We have to take care of that and keep that alive so that we can continue living.”

The battle to protect their land and people from the coal industry began in the early 1970s, when the Northern Cheyenne discovered that the Bureau of Indian Affairs had leased roughly half their reservation to coal companies for strip mining without full tribal consent, at rates below market value (12 to 17 cents a ton).

In an effort to demystify coal mining, government and industry officials invited Northern Cheyenne leaders to visit large strip-coal mines in nearby regions. The visit had the opposite of its intended effect: Horrified by the environmental degradation they witnessed, the Tribal Council submitted a 600-page petition to the Secretary of the Interior in 1973 to cancel all lease agreements.

After years of advocacy, the Secretary of the Interior indefinitely suspended the coal leases on the reservation in 1974. Two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case Northern Cheyenne Tribe v. Hollowbreast that the Tribe collectively owns the mineral rights beneath its land. Even through economic hardship, they’ve never sold the coal.

“The Northern Cheyenne, despite the poverty conditions we’ve been under, we will not sell anything that has to do with Mother Earth,” says Alden. Part of the reason, she says, is the suffering their ancestors endured — fighting multiple battles, forced displacement, and cultural erasure during the Native American boarding school era — to keep their land and identity.

“When we destroy the air, land, and water, we destroy our language, culture, and our identity,” says a traditional Northern Cheyenne Chief, Phillip Whiteman Jr. “It’s called a genocide and extermination.”

The Rosebud coal mine in Colstrip, Montana, north of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. (EcoFlight)

After winning fights to protect their own land, the Northern Cheyenne confronted off-reservation coal development. Many of these legal battles involved trying to keep coal in the ground as they challenged mining permits, eventually pushing to end federal coal leasing across the entire region.

With legal support from Earthjustice, they’ve continued this fight through a series of policy wins and setbacks: after President Obama paused new coal leasing in 2016, the first Trump administration reversed the move the following year. Earthjustice attorney Jenny Harbine immediately sued on behalf of the Northern Cheyenne, winning back the pause on coal leasing.

“It’s such an honor to be able to represent them given their rich experience and expertise [in the courts],” says Harbine. “From working with the Northern Cheyenne, I’ve learned lessons in perseverance and taking the long view.”

A major step forward came in 2024 when, after two rounds of Earthjustice litigation, the Biden administration officially ended new coal leasing in the Powder River Basin.

Part of the reason for the decision was recent data showing a 40% decline in coal power consumption over the past decade as clean energy sources have become more affordable. In 2024, wind and solar surpassed coal power in the U.S. for the first time.

Charlee Rising Sun, the former Sustainable Energy Manager for the Northern Cheyenne tribe, walks by a solar mount she installed in Lame Deer, Montana. (Louise Johns for Earthjustice)

But now, with Trump back in office and set on resuscitating coal, the Tribe is gearing up for future battles. While the administration began its process to reopen the Powder River Basin to new coal leasing, Congress passed two resolutions to short-circuit public engagement and do industry’s bidding. In August, the administration greenlit a massive expansion at Montana’s Rosebud coal mine — the strip mine that feeds the Colstrip coal plant whose smokestacks loom over the Northern Cheyenne’s reservation.

The plant, located just 20 miles north of the Northern Cheyenne’s reservation in Colstrip, MT, represents the remnants of the coal industry Trump seeks to revive. Nearly 40 years old, it is the nation’s most polluting coal-fired power plant, threatening air quality on the reservation.

While Units 1 and 2 of the plant were retired in 2020, Units 3 and 4 remain the only operating coal-fired units in the country without modern pollution controls to filter harmful particulate matter, which is linked to heart and respiratory disease. This pollution also acidifies lakes and streams, disrupts biodiversity, and depletes soil nutrients.

In 2023, the American Lung Association assigned Rosebud County — where the reservation is located — an “F” for high particulate matter. Before Units 1 and 2 closed, the Clean Air Task Force estimated 48 premature deaths annually from plant emissions, along with 5 hospital admissions, 20 heart attacks, and 540 asthma attacks.

“Now scientists are starting to say we are seeing an increase in lung cancer, multiple sclerosis (MS), nervous system disorders, and stuff that lowers your immune system,” says Alden, whose husband — a former plant worker — died of lung cancer.

The Northern Cheyenne Reservation is protected under Class I air standards, a level of protection typically reserved for national parks. The Tribe was the first in the nation to secure this designation, providing a powerful legal tool to advocate in decisions affecting their air quality.

Beginning in 2017, the Tribe urged the Environmental Protection Agency to strengthen limits on particulate matter emissions from power plants like Colstrip. In 2024, the agency tightened air pollution standards for coal plants. But this spring, the Trump administration moved to repeal those protections and granted blanket pollution exemptions to 68 coal-fired power plants, including Colstrip, undermining the new standards. Earthjustice is currently suing to block these exemptions.

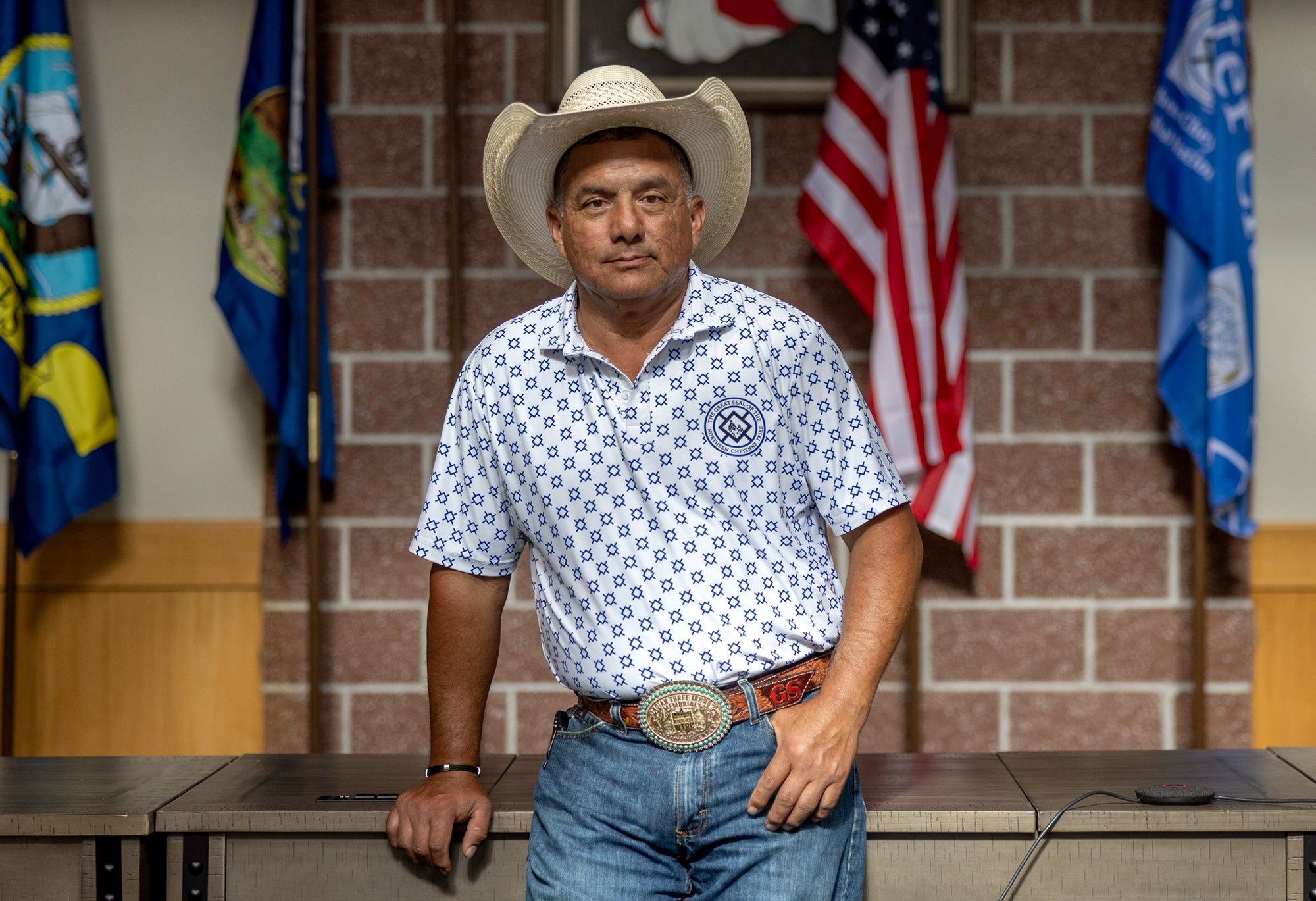

Gene Small, the president of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, stands in the flag room of the tribal headquarters in Lame Deer, Montana on July 3, 2025. (Louise Johns for Earthjustice)

Tribal members say their relationship with Colstrip is complex. The power plant has been a source of employment on the reservation, where some estimates report that half to two-thirds of adults are without steady work.

“You’ve got 80-plus employees working [at Colstrip] that provide for families here on the reservation,” explains Tribal President Gene Small, himself a former coal mine worker. “So I’m not opposing [coal] when somebody wants to go to work and provide for their own.”

Despite this history, the Northern Cheyenne are increasingly interested in renewable energy, especially solar. In 2016, the Tribe passed a clean energy ordinance committing to carbon neutrality as a path to employment and energy sovereignty.

A number of projects have been in the works since. The Tribe is in the midst of its White River Community Solar Project. The project, funded by a $3.2 million Department of Energy grant, aims to enable the reservation to power more than 100 homes and several small commercial sites through solar energy.

Part of the project included workforce training for 11 tribal members at Red Cloud Renewable — a two-week solar training program to gain hands-on experience building solar arrays. So far, the project has put in place 15 residential solar systems, plus three arrays for Tribal facilities.

“[As we] try to be our own sovereign nation, having our own source of energy helps tremendously. It’s huge to have solar,” says Charlee Rising Sun, the Tribe’s former sustainable energy manager who participated in the solar training program.

Even those skeptical about the benefits of solar energy are beginning to see a drop in their energy bills — which are often high due to Montana’s harsh winters, poorly insulated homes, and overcrowding.

President Small tells a story about an elder on the reservation whose monthly energy bill jumped from $20 to $350 when his solar system was temporarily out of commission.

While the Tribe was poised to expand on this progress with the extension of solar power to 100 to 140 additional households, the Trump administration recently withdrew the Tribe’s $7.4 million grant for the project.

Despite the blow, the Tribe has continued to push for a cleaner energy future through other avenues, including utility rate cases — most recently with NorthWestern Energy. Their message has been consistent: With abundant, tribally developed clean energy available, utilities don’t need to rely on coal to power Montana.

People take part in the Northern Cheyenne 4th of July Chiefs Powwow, which took place over three days, in Lame Deer, Montana. (Louise Johns for Earthjustice)

Though the current administration’s push to revive coal threatens this clean energy progress — as well as federal funding cuts and tariffs — the Northern Cheyenne are prepared to fight for a better future, as they have for over a century.

“Our lands are too important to let them be destroyed by mining,” says Alden. “We hope renewables will provide an economic and climate lifeline for our community. As our ancestors taught us through their stories, we will never stop fighting for our people.”

Established in 1993, Earthjustice's Northern Rockies Office, located in Bozeman, Mont., protects the region's irreplaceable natural resources by safeguarding sensitive wildlife species and their habitats and challenging harmful coal and industrial gas developments.