Northwest Tribes Demand Action for Salmon and Orca Restoration

Tribes call for dam removal and restoration of healthy salmon and orca populations during emotional two-day summit.

This page was published 2 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

More than 15 Northwest Tribal Nations gathered in early November to share stories about salmon, orca, water, and the land — and to demand the federal government uphold Tribal treaty obligations to recover and restore salmon in the Snake River and Columbia River Basin.

During the two-day Rise up Northwest in Unity gathering at the Tulalip Resort in Washington, more than 300 people attended in person while more tuned in virtually. Dozens of speakers — including Tribal leaders, conservationists, and youth — expressed sorrow, loss, fear, anger, and responsibility over diminishing populations of salmon and orca whales. Without immediate and urgent action, both are now facing extinction.

At the same time, speaker after speaker also offered hope, excitement, and resolve.

Since the gathering, momentum is building – along with real progress. In a historic announcement on Dec. 14, the White House, the States of Oregon and Washington, and four Columbia Basin Tribes unveiled a new plan for Columbia River Basin restoration. Based on a new Tribal-state initiative backed by federal funding and other commitments, initial steps are beginning to replace the services provided by the four lower Snake River dams, paving the way to breach the dams to prevent salmon extinction.

For three decades, Earthjustice has represented fishing, environmental, and renewable energy groups in court battles to protect fish in the Columbia and Snake rivers from harmful dams. We are celebrating this momentous step forward, and we will continue to push the Biden administration and Congress to finish the job. In conjunction with the states of Oregon and Washington and the Nez Perce, Yakama, Warm Springs, and Umatilla Tribes, we have agreed to put our litigation on a multi-year pause as long as implementation of the plan moves ahead.

At the opening of the Tribal gathering in Tulalip, Yurok Tribe member Amy Cordalis, an attorney and co-principal of the Ridges to Riffles Indigenous Conservation Group, offered words of encouragement based on her Tribe’s recent success beginning restoration of the Klamath River in Northern California.

Her Tribe, alongside others, is helping lead the world’s largest dam removal and river restoration project to date, offering a model for what is possible. Once the third largest salmon-producing river on the West Coast, the Klamath is now down to 1-3% of its historic runs.

Soon, however, the fish will return. One dam, Copco 2, is already gone, and the next dam, Iron Gate, will be removed in December 2024.

“Those salmon are going to come home … and spawn in places they haven’t been able to go in 170 years,” Cordalis told the gathering. “If we can do it on the Klamath, we can do it on the Snake.”

Amy Cordalis talks with coalition partners at a 2018 legal meeting at Earthjustice headquarters in San Francisco. (Martin do Nascimento / Earthjustice)

River People and Salmon People

Like the Klamath, wild salmon runs in the Snake and Columbia Rivers survive at small fractions of their historic populations. In some areas, no salmon return. More than half of the original spawning and rearing habitat for salmon in the Columbia Basin is blocked by dams.

On the first day of the gathering, retired Spokane Tribe chair Carol Evans shared that her people, who are river people and salmon people, live in one of those blocked areas. Salmon stopped migrating there after the Grand Coulee Dam was completed in 1942, separating them from their salmon relatives for close to 100 years.

“Since time immemorial, my people lived off the salmon,” Chair Evans said. “They sustained about 50-60% of their diet. The salmon gave up herself so we could exist, so we could be here. We must give up ourselves to help her continue, to help us sustain our way of life.”

Chair Evans said that the Spokane Tribe and other Upper Columbia Tribes have centered their efforts on reintroducing salmon and steelhead back into waters now blocked by the dams. In September, the Biden administration committed more than $200 million toward salmon recovery in the Upper Columbia Basin to be paid over 20 years, in return for settling litigation by some of these tribes.

She added that losing culture, language, and salmon has had a traumatic impact on her people, deeply affecting their health and well-being because salmon and people are so closely intertwined.

Nimipuu Health Medical Director Kim Hartwig of the Nez Perce Tribe, speaking on a women’s panel the next day, echoed that sentiment. “Our ways of life and living offer much greater healing than an insulin injection or a pill that I can give,” she said. “I truly feel that’s where we need to go to heal communities in Indian Country.”

Members of the Yurok Tribe fish for salmon in the Klamath River. (Martin do Nascimento / Earthjustice)

A System Out of Balance

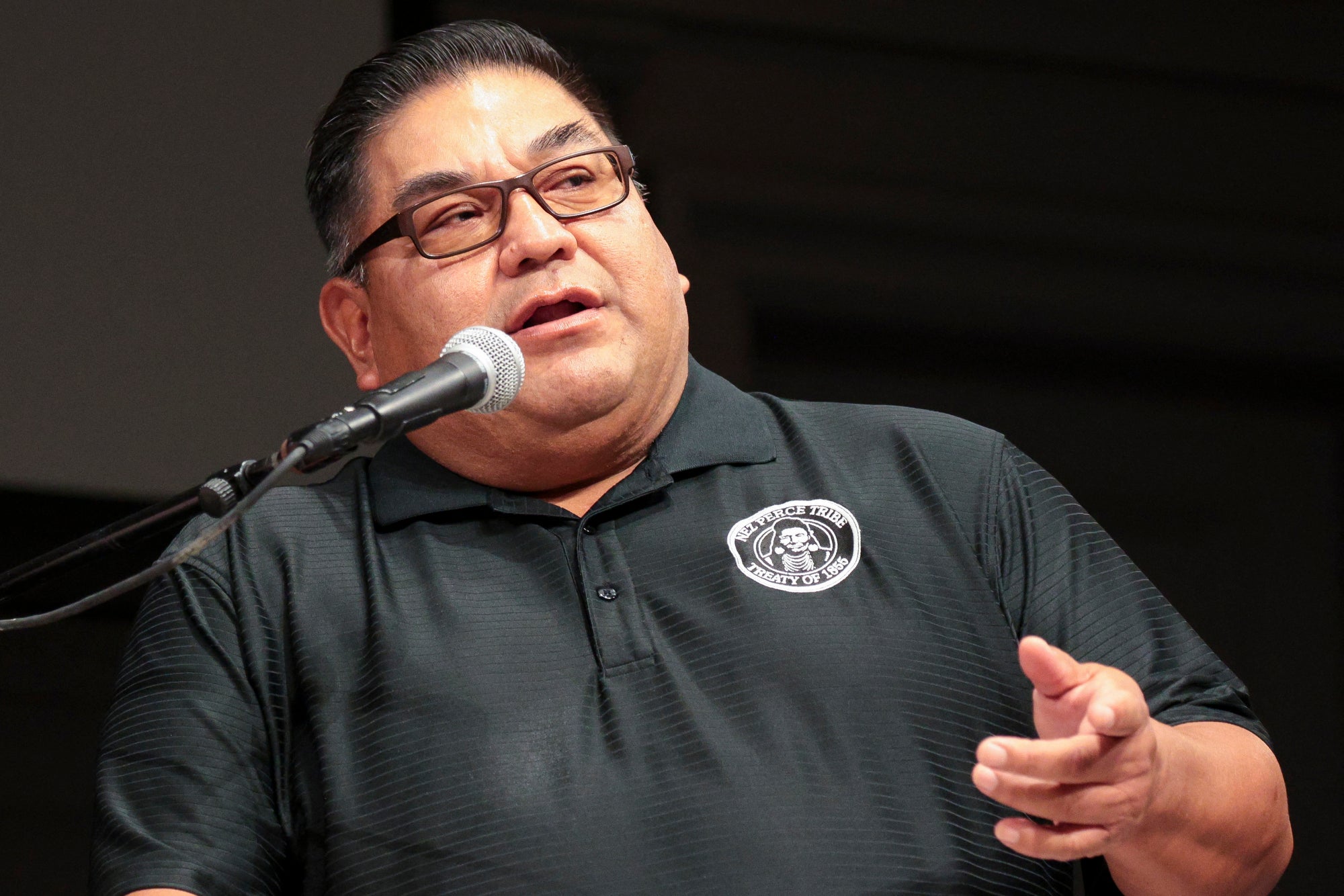

Nez Perce Chair Shannon Wheeler said the gathering — an extension of the Salmon Orca Summits held previously — was organized to support the need for Tribes to work together to recover salmon in the Columbia River Basin. That includes urging the federal government to remove the four lower Snake River dams, the largest salmon producing tributary to the Columbia River.

Today, 13 species of Columbia River Basin salmon and steelhead are listed under the Endangered Species Act, including all remaining salmon and steelhead populations in the Snake River Basin. That’s despite many years and billions of federal dollars spent on efforts to protect salmon. The problem is those efforts don’t address the root cause of population declines — the dams. Biologists say removing the four dams on the Lower Snake River is the single best action we can take to help salmon recover — once again providing a free-flowing river for salmon migration and access to some of the region’s best remaining cold-water spawning habitat.

The loss of salmon has reverberated through the food web. The endangered Southern Resident killer whales, which hunt for threatened Chinook salmon in Puget Sound and, in many months, off the mouth of the Columbia, are also teetering on the brink of extinction with only 75 whales left across three pods, or social groups.

In 2021, the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians and the National Congress of American Indians passed resolutions in support of breaching the dams.

The Nez Perce Tribe, alongside others, has long been involved in litigation to take down the dams. Part of that litigation hinges on Tribal treaties that have not been upheld by the federal government, Chair Wheeler said. When tribes along the Snake River ceded millions of acres of land to the United States, the federal government promised to protect their rights to gather, hunt, and fish for salmon as they always had.

The treaties, Chair Wheeler explained, are also meant to uphold tamáalwit, the spiritual relationship that teaches Nez Perce members to live and care for the land. Building the dams and now refusing to remove them when they are known to harm salmon is a breach of that promise and that obligation owed to Tribes.

“We’re seeking balance again,” Chair Wheeler said, “so the salmon have a chance, the steelhead have a chance, the lamprey have a chance, the orca have a chance, and we as Native people have a chance. It’s difficult to maintain a culture without that interaction with the land.”

Nez Perce Tribe Chairman Shannon Wheeler speaks during the “All Our Relations Snake River Campaign” event, an Indigenous-led campaign traveling through the Northwest to bring attention to the need to remove the four lower Snake River dams, in Seattle, Washington on October 1, 2023. (Jason Redmond / AFP via Getty Images)

“What Are You Going to Do About It?”

As the earth faces a rapid, unprecedented, and catastrophic loss of biodiversity, it is more important than ever to take urgent action to protect the diverse range of species and habitats on which we all rely. Our own fate is inextricably linked to the plants and animals with which we share this planet, a point Tribal speakers made repeatedly over the two-day summit.

In his final comments, Chair Wheeler challenged all those who were listening to ask the federal government to uphold Tribal obligations by restoring healthy and abundant wild salmon and steelhead populations across the Columbia and Snake Rivers. He made it clear that the obligation was broader than the Tribes and others at the gathering, extending to all U.S. citizens.

“What are you going to do about it?” he asked. “It was nice when you wanted something from us, you know when you wanted passage through our lands, and you wanted lands, and now that you have that, you forgot about your obligation. Well, we’re here to remind you of that obligation.”

Lower Granite Dam, one of the four lower Snake River dams that Earthjustice is fighting to remove. (Chris Jordan-Bloch / Earthjustice)

In long-standing litigation aimed at restoring salmon and removing the dams, Earthjustice represents conservation, fishing, and renewable energy groups. Earthjustice’s plaintiffs are fighting alongside Tribes, including the Nez Perce, as partners and allies.

Established in 1987, Earthjustice's Northwest Regional Office has been at the forefront of many of the most significant legal decisions safeguarding the Pacific Northwest’s imperiled species, ancient forests, and waterways.