Conversation with Buck Parker

Buck Parker reflects on how he got involved with Earthjustice and how he helped shape its direction during a time when conservation efforts evolved into the powerful environmental movement.

This page was published 10 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

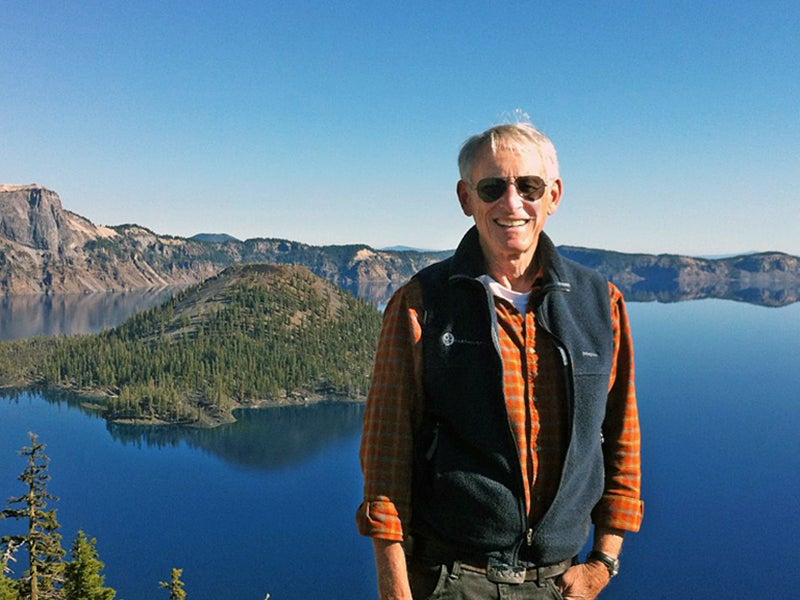

Vawter “Buck” Parker describes himself as “the kid in the back of the car daydreaming and looking at the passing landscape” as his family took long rides through Oregon, where he grew up. Those years set him on course for a lifetime of protecting the wild, first as a private lawyer, then for 35 years with Earthjustice, which he led for more than a decade. As he retires to his home in Hood River, Buck reflects on how he got involved with Earthjustice and how he helped shape its direction during a time when conservation efforts evolved into the powerful environmental movement.

Your experiences as a young boy helped shape your destiny. What happened?

I grew up in the small town of Hood River, Oregon, and my family would often travel along the Columbia River, passing Celilo Falls. Native Americans for thousands of years had fished for salmon there from rickety scaffolds and ladders over these gigantic rapids. It was THE most important trading and meeting place of Native Americans in that part of the Northwest and the centerpiece of their cultural heritage. But in 1957, the Dalles dam was completed and I watched the rapids disappear. It was hard to believe. Then, as I grew older, I watched the move toward clear-cutting of forests where we camped and hiked. I just felt something was wrong, but, like Celilo, not too many people talked about it. Over time I became aware that there were other people like me who were asking questions about what we were doing. I discovered there was a name for people like me—environmentalist.

Environmentalism came of age in 1970 with the first Earth Day. How did that influence you?

Earth Day went right by me because I was with the Army in Vietnam. I had been drafted out of Harvard law school—where I took the school’s first environmental law course. But when I got out of school I took a job with a firm in Portland, Oregon, and became active in the local Sierra Club chapter. I put in a lot of pro bono time advising conservation groups and protecting wilderness.

I got to know some people working at the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund (an offshoot of the Sierra Club), which we eventually renamed Earthjustice. I joined as litigation coordinator in what was mostly a liaison role between lawyers and clients. In time I took on more responsibility and was named vice president. I had considered trying to establish a law firm in the Northwest with a public interest emphasis working for nonprofit clients, but I liked being part of a larger, experienced organization and strongly supported its opening a Northwest office.

Why did Earthjustice transform into a fullfledged environmental law organization?

In the 1980s we spent years litigating to protect Admiralty Island in southeast Alaska, but to close the deal we needed congressional action. None of our clients had lobbying staff to spare, however, which meant years of our efforts would fail for lack of legislation. Then, in the 1990s, as we litigated over the spotted owl to protect old-growth Northwest forests, Congress passed legislation that took away the power of courts to hear challenges to forestry plans for a year. At that point it became clear that we needed to develop comprehensive communications and political strategies around our cases and the issues they raised. Until then we had left those aspects up to the client organizations we represented, but they were often too small to match the lobbying and PR campaigns mounted by the corporations we were taking on.

We felt we owed it to ourselves and to our donors to make sure our cases really brought about the ultimate changes we were seeking. So we began trying to shape public opinion around the issues raised by our cases. It was a very small effort at first, but that thinking eventually led to the creation of the policy and legislation department and the communications department.

How did the environmental movement evolve from classic conservation struggles like protecting rivers and wildlife?

Not all the early environmental cases were about wilderness and parks. A lot of them were about highways and rivers and raised human health issues— air-quality impacts on marginalized communities, for instance. Cases over nuclear energy and coal-fired power plants also raised health concerns. As time went on, we all found it harder to segregate wilderness and wildlife issues from human health issues, and in fact there was no compelling reason to do so. The root cause—the desire of some to reap the benefits while imposing the costs on others—is so often one and the same.

When people speak of Earthjustice’s Arctic work, your name invariably comes up.

I always was interested in the Arctic, especially after a threeweek backpacking trip through the Brooks Range in the late seventies. But up until a few years ago not too many people paid attention to what was happening there. Our Alaska office has been engaged in Arctic issues since the mid-1990s, primarily around proposals for offshore oil development. Around 2006 a number of us, including Trip Van Noppen [who succeeded Buck as Earthjustice’s president], agreed that we needed to engage on a more international scale. Later, when I stepped down as executive director, Trip offered me the chance to continue to work part-time on Arctic issues. At the time just about every major oil company in the world and all of the five countries adjacent to the Arctic Ocean envisioned making a lot of money in offshore oil. Only recently has that vision crashed. For one, the Gulf oil spill brought home that even in the best situations with the best resources at hand you can’t control offshore oil spills. And then there is the Shell drilling saga. Earthjustice played a big role in rousing domestic opposition, which drove home the real costs of offshore oil development and the fact that we needed to invest in a lot more safety. Three years ago, when Shell’s drilling platform, the Kulluk, broke loose from its towline and ran aground in the Gulf of Alaska, I knew we would ultimately win.

You’ve played a significant role representing Earthjustice and the U.S. on the Arctic Council. Describe the council and its work.

The Arctic Council is primarily a forum where the eight Arctic countries—the United States, Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia—explore ways in which they should cooperate to protect the Arctic and its peoples even as they seek economic development. It is not itself a rule-making body, but it is a place where agreements can be negotiated among the Arctic countries or policies harmonized around such issues as search and rescue, oil spill preparedness and wildlife protection, and where scientific research projects can be prioritized and coordinated. It is unique among international bodies because it provides a place at the table for Native peoples, and its emphasis is on environmental protection. The other important thing is that all of the nations, including Russia, are trying to work together and continue to cooperate on Arctic issues. We lose sight of that positive fact, largely because the media prefers to play up potential international conflict.

Out of all the work that Earthjustice does on climate-related issues, what stands out to you?

There are the cases we are bringing that will lead to the closure of existing coal-fired power plants. And there are cases over the export of U.S. coal and oil, particularly relating to rail transportation and to export facilities along the West Coast. All of these cases are extremely important because of the danger that fossil fuels present to climate and human health. In Oregon, where I now live, coal and oil trains pass through Columbia River Gorge, which would be the main rail artery if more fossil fuel resources are allowed to be exported through the Pacific Northwest. Those trains are going to have to run right through my town and hundreds of other small towns and cities along the line. They present a huge risk to waterways and a huge risk to people. I’m proud that Earthjustice is a leader in fighting both the export terminals and the explosive trains that would serve them.

Do you have any advice for the next generation of environmental lawyers?

Be a team player: Changing policy requires a lot of people working together at a lot of different levels. Also, recognize that environmental fights are long-term commitments. Change usually doesn’t come rapidly, and the work can be very frustrating. And then, suddenly, public opinion or economics shift—often catalyzed by litigation—just when you were about to give up hope. I’ve had that experience many times, and others will, too.