What Will We Lose if Oil and Gas Drilling Expands in Arctic?

Aggressive new drilling proposed in northern Alaska poses grave risks to the planet — and to a vast and rare Arctic ecosystem.

The Trump administration plans to make unprecedented push to maximize oil and gas drilling in Alaska by leasing ecologically sensitive lands and waters to the highest-bidding fossil fuel company. This new and aggressive drilling would cause irreparable harm to wildlife, birds, fish, and people who depend on this habitat, along with the broader destruction to Alaska and the planet from the burning of fossil fuels.

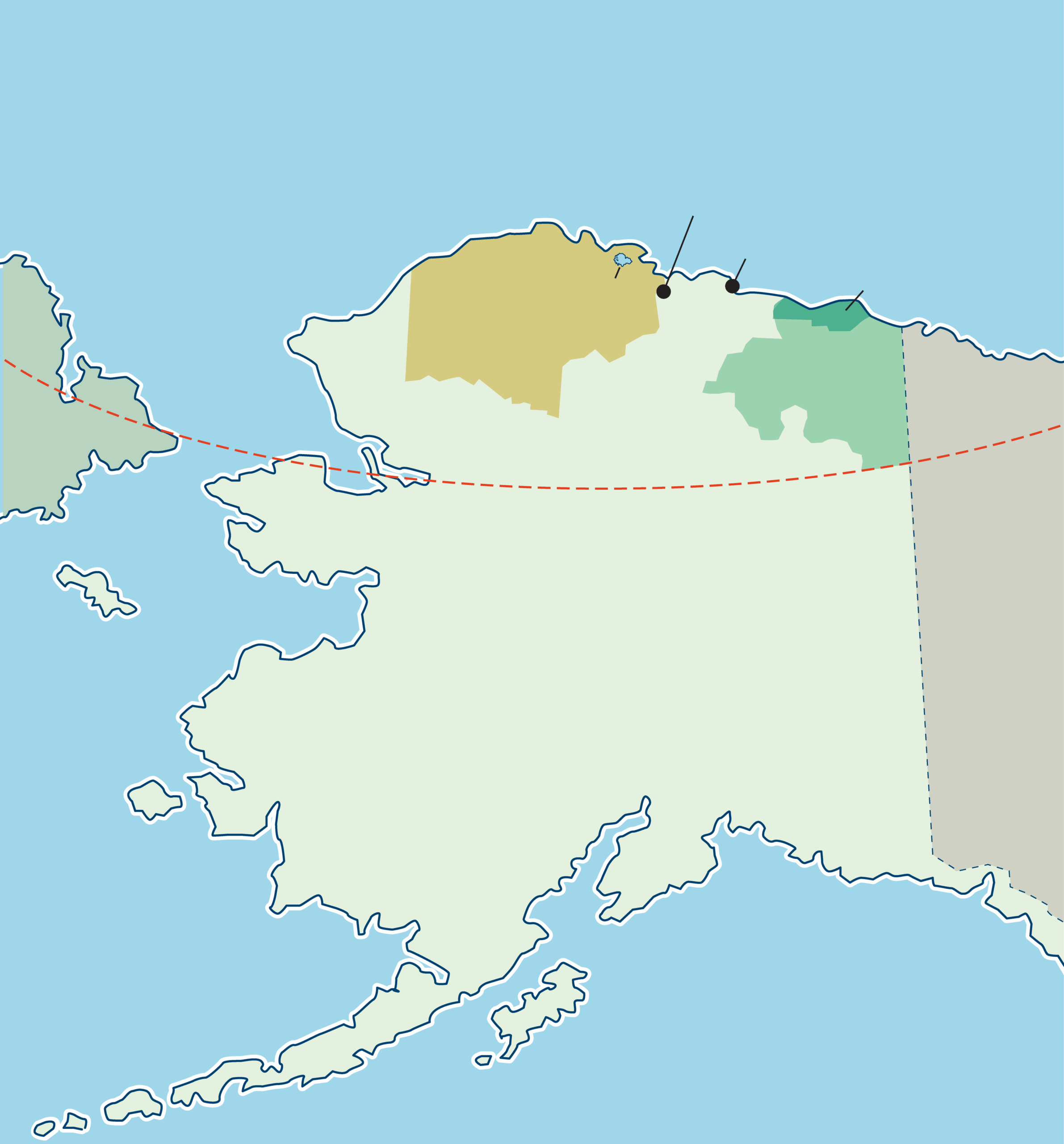

To understand what’s at stake, it’s helpful to understand some geography. Following the discovery of the Prudhoe Bay oil field in 1968 and the Kuparuk field two years later, the region around these oil fields on Alaska’s North Slope quickly mushroomed from a remote and sparsely populated region of endless tundra and vast wetlands into the state’s largest industrial hub, fueling oil and gas development.

While the epicenter of Arctic drilling remains focused in and around Prudhoe Bay, oil and gas development has fanned out to the west, east, and south, and to the north, into the nearshore state waters of the Beaufort Sea. This part of the Alaska is now crisscrossed with drilling pads and wells alongside ice and gravel roads, pipelines, processing facilities, buildings, and airports.

Flanking Prudhoe Bay to the west and east, however, are two vast and mostly untouched public land tracts that oil and gas drillers have long wanted to expand into. To the west is the Western Arctic, also known as the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska (NPR-A), where expansion has already begun due to Willow and other projects. To the east is the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where some leasing and exploration has taken place, but no commercial drilling has yet occurred. The Arctic Ocean, aggressively pursued by the oil industry in years past, is currently entirely free of oil leasing and development, with only limited drilling from gravel islands in state waters in the Beaufort Sea.

Arctic Ocean

Beaufort

Sea

Nuiqsut

Chukchi

Sea

Prudhoe Bay

Coastal Plain

Teshepuk Lake

Western Arctic(National Petroleum

Reserve-Alaska)

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

Russia

Arctic Circle

Canada

Alaska

Bering

Sea

Gulf of

Alaska

Peter Hoey for Earthjustice

The Western Arctic (also called the "National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska" or NPR-A) is home to many millions of acres of specially designated lands because of their ecological and cultural importance. This includes Teshekpuk Lake, a wetlands area critical for migratory birds from around the world.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is the country’s largest national refuge and home to diverse wildlife and Indigenous communities. Within the Arctic Refuge’s Coastal Plain are the calving grounds of the Porcupine Caribou herd.

Earthjustice has long defended these regions from harmful oil and gas exploration and development — and will continue to do so amid these increased threats.

Polar bears near the Beaufort Sea on Alaska’s North Slope. (Stephanie Powell / Getty Images)

Threats from climate change

Oil and gas development in the Arctic exacerbates climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions resulting from reckless drilling harm not only Alaska, but the entire planet, adding fuel to a climate crisis that is spiraling out of control. In Alaska, these harms include temperatures that are warming at four times the rate of the rest of the world, leading to decreased sea ice, rapidly eroding coastlines, and ocean acidification. As an icy layer of tundra known as permafrost thaws, it releases methane — a greenhouse gas four times as potent as carbon dioxide — into the atmosphere, further intensifying climate impacts and causing a dangerous feedback loop.

The loss of sea ice, important for the survival of many Arctic species including polar bears, walrus, and seals, further contributes to warming because ice-free water, which is darker in color, absorbs more solar energy than reflective ice. As ocean temperatures rise, more ice is lost, resulting in even more warming.

A warming Arctic threatens wildlife, birds, and fish — and also people. Alaska Native people, in particular, face new threats to their food security and traditional ways of life as subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering has become more difficult. Communities and infrastructure are also at risk from thawing permafrost, rapid coastal erosion, and changes in water sources associated with climate change.

Polar bears live on the sea ice and coastal plain along the entire North Slope. With declining sea ice, biologists are documenting more onshore denning and foraging for food on shore for longer periods of time. This causes stress to polar bear populations, which are not adapted to hunting on land, and brings them into more frequent conflict with communities and people working in the oil industry, which could result in more bears being killed.

In addition to the loss of calving grounds for caribou, and other challenges to caribou caused by climate change, infrastructure such as roads and industrial activity have been found to disrupt caribou movement, posing further risks to the health of four herds that use Alaska’s North Slope.

A dunlin searches for food among short green grasses in the Western Arctic, in the area close to Lake Teshekpuk. (Kiliii Yuyan for Earthjustice)

Threats to the Western Arctic

The Western Arctic, also known as the NPR-A, is the nation’s largest intact tract of public land, bordered by the Chukchi Sea to the west and the Beaufort Sea to the north and the Brooks Range to the south. Managed by the Bureau of Land Management, it covers 23 million acres of diverse habitats, ranging from tundra and wetlands to mountain foothills, grassy uplands, riparian areas, and river deltas.

Earthjustice’s work to protect this area includes a legal challenge to ConocoPhillips Alaska’s Willow development, which is already under construction. As a result of our litigation, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals recently required the Department of the Interior to reconsider its approval of Willow. It may not stop the project but we’re waiting to see how the government will respond.

In the meantime, the Trump administration has said it plans to remove protections against drilling within certain sensitive areas within the Western Arctic, and approve a plan allowing oil and gas drilling on 82% of the public lands within the NPR-A. The recently passed budget reconciliation bill, too, mandates five lease sales within 10 years, including one within one year, fast-tracking the push for oil development in the region. The Western Arctic is home to caribou, muskoxen, fish, polar bears, wolverines, and moose, and contains one of the largest wetland complexes in the circumpolar Arctic, attracting vast numbers of waterfowl, shorebirds, raptors, and other birds. Birds come from all corners of the globe, and the region hosts some of the highest densities of breeding shorebirds in the world.

The NPR-A was originally established in 1923 as a petroleum reserve for the U.S. Navy, then transferred to the Department of the Interior in 1976. When Congress transferred management to the Bureau of Land Management in 1976, it recognized the area’s rich ecological values and required the agency to protect fish, wildlife, and habitat.

While the entire Western Arctic provides important habitat for birds, fish, and wildlife, the Department of the Interior under previous administrations designated five Special Areas within NPR-A because of their unique role in protecting biodiversity:

Teshekpuk Lake Special Area: Comprising 3.6 million acres and located on the eastern edge of the Western Arctic, close to existing oil and gas fields, Teshekpuk Lake would be entirely open to oil leasing under Trump’s proposed plan. This special area was primarily established for its importance to nesting and molting birds, particularly migratory geese such as snow geese, greater white-fronted geese, and Pacific black brant. In fall, hunters and bird watchers flock to see these birds as they pass through the lower 48. The Teshekpuk Lake area is also critical to the yellow-billed loon, which relies upon the deep-water lakes for nesting, and provides a safe place for the Teshekpuk Caribou Herd to give birth to calves. The herd lives year-round on the North Slope and is an important subsistence resource for nearby Iñupiat communities.

Colville River Special Area: Covers 2.4 million acres and provides exceptional habitat for nesting birds of prey such as gyrfalcons, peregrine falcons, and golden eagles. The area is also a vital habitat for fish species like whitefish and northern pike that are important for subsistence. It would be eliminated under Trump’s proposed plan.

Utukok River Uplands Special Area: The largest Special Area within the Western Arctic, covering 4 million acres. It provides critical habitat for grizzly bears, wolves, moose, and wolverines and includes the calving grounds for the Western Arctic Caribou Herd, one of three caribou herds that use the NPR-A and a herd that Alaska Native communities depend on throughout northwestern Alaska.

Kasegaluk Lagoon Special Area: One of the largest and most intact coastal lagoon ecosystems in the world. It provides habitat for beluga whales, as well as seals, walrus, polar bears, and migratory birds. An important migratory resting area for Pacific black brant and the threatened spectacled eider.

Peard Bay Special Area: Peard Bay provides important habitat for ice seals as well as nesting spectacled eiders and migrating shorebirds.

Kasegaluk Lagoon and Peard Bay Special Areas: These two coastal lagoon areas in northwestern Alaska provide habitat for beluga whales, seals, walrus, and migratory birds. These large coastal lagoons provide critical migratory resting areas for Pacific black brant and the threatened spectacled eider.

A caribou herd foraging on vegetation at the ledge of a hill adjacent to the Hulahula River, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.(Alexis Bonogofsky for USFWS)

Threats to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

To the east of the Western Arctic and Prudhoe Bay, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge covers about 19.3 million acres in northeast Alaska and is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It borders Canada to the east and the Beaufort Sea to the north. The Department of the Interior established it as a national wildlife refuge in 1960, and it has been the largest such refuge in the country ever since.

Earthjustice has long defended the Refuge against oil and gas development. In 2021, we challenged the first Trump administration’s plan to pursue oil and gas development in the refuge along with leases purchased at an extremely low price by the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA), a State of Alaska sponsored corporation. That lawsuit is currently on hold, but Earthjustice stands ready to again defend against these leases, as well as other threats to the Refuge that don’t follow the law.

Current threats to the Refuge are similar to those facing the Western Arctic. In addition to defending the leases it issued during its first term, the Trump administration has vowed to enact a new drilling plan maximizing leasing, while the Budget Reconciliation Bill requires four new oil and gas lease sales in the Coastal Plan of the Refuge.

The Refuge includes diverse habitats that support a broad range of species including caribou, brown, black and polar bears, Dall sheep, moose, foxes, muskoxen, and numerous birds.

The calving grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd lie within the coastal plain of the Refuge, an area long sought for oil and gas development. The herd and the coastal plain are sacred to the Gwich’in people who live near the Refuge’s south border and have depended on the Porcupine Caribou Herd for thousands of years. The Refuge’s coastal plain also provides an important denning area for female polar bears in winter.

A bowhead whale and calf surface in the Arctic Ocean. (Amelia Brower / NOAA)

The ecological significance of the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean teems with life and supports a complex ecosystem from plankton, fish, and migratory birds to large marine mammals, including polar bears, walrus, and bowhead whales. Endangered bowhead whales migrate through the area in the spring and in the fall, and they are very sensitive to industrial disturbances like drilling. Introducing massive industrial activity into this region would put many of these animals in peril, including from inevitable oil spills. Earthjustice is currently involved in two related legal challenges to protect oceans, including the Arctic Ocean, from offshore oil drilling.

All of these areas now under threat in Alaska’s Arctic are irreplaceable public lands that deserve our protection.