Meet the Community that Stopped an Environmental Power Grab by the Trump Administration

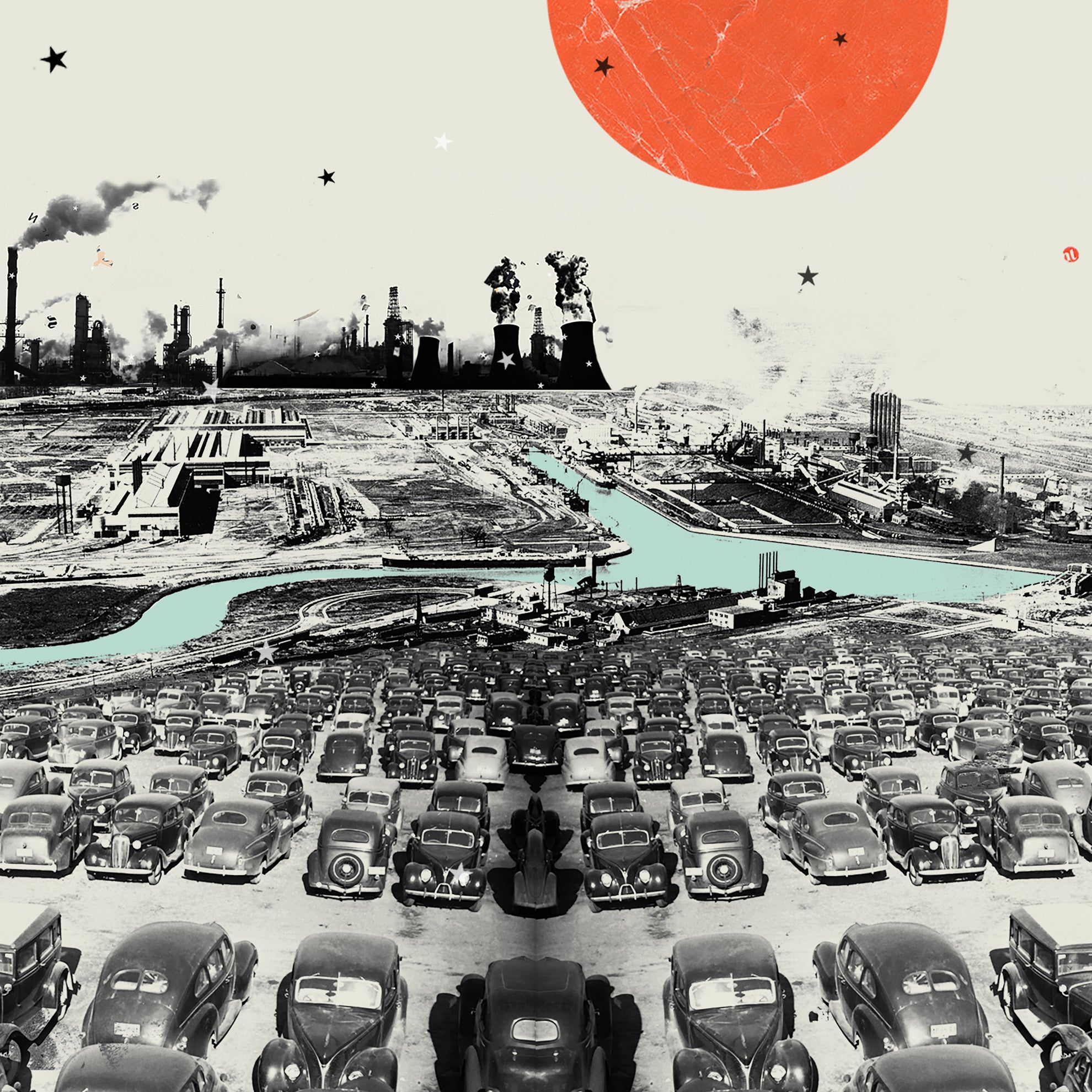

After decades of pollution, a community that faced unprecedented actions by the Trump DOJ claims victory for their health and environment.

Meet the Community that Stopped an Environmental Power Grab by the Trump Administration

After decades of pollution, a community that faced unprecedented actions by the Trump DOJ claims victory for their health and environment.

February 8, 2021

River Rouge, Michigan, a city that neighbors Detroit, is not the same city full of hope that drew Vicki Dobbins’ parents and other Black families from the Deep South to its factories and steel mills in the 1940s.

“I bet you of 50 or 60 homes, I can’t find five healthy men,” she says. “There was a time when there was a man in every household.”

Now, she asks: “Where are the men? Where are the children?”

Dobbins’ father took a job in the Ford factory near this largely blue-collar town when he arrived, and he bought a house soon after.

“It was a new community,” Dobbins says. “It was the quintessential African American community. But nobody talked about the pollution.”

But the confluence of steel plants, car factories, power plants, and a refinery has taken its toll. Toxic pollutants linked to cancer, lung illnesses, and other chronic diseases have drained the vitality of the community.

“I’ve never seen so many young people pass away with bone cancer, liver cancer, lung cancer,” says Dobbins. “People in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. You think: How can this be possible? This person never drank or smoked and exercised all the time.”

Deteriorating public health in Detroit and the surrounding suburbs has sparked numerous investigations into the causes. In 2012, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality found that the air surrounding River Rouge contains the state’s highest levels of sulfur dioxide (SO2), a toxic gas released by the burning of fossil fuels, which is known to damage human health as well as trees and other plant life. The report attributed those critical levels largely to emissions from local steel and coal power plants.

Dobbins and other residents are fighting to hold industrial polluters accountable for the health harms inflicted on their community. In May 2020, they won a major victory.

As part of a settlement agreement, local utility company DTE Energy agreed to retire three coal power plants that have contributed heavily to the region’s toxic legacy. The company also committed to provide $5.5 million in funding for clean electric school and transit buses, as well as an additional $2 million for other community-based projects to improve air quality in River Rouge, the neighboring town of Ecorse, and the 48217 ZIP code in southwest Detroit, the most polluted ZIP code in Michigan.

The settlement, though modest, offers hope for a new beginning in River Rouge. Major sources of pollution will be removed, and the city will begin to reclaim its environmental health. The outcome also demonstrated the potential of dogged grassroots activism, supported by aggressive litigation, to address a critical issue for the residents — a model they can build upon to continue seeing justice served.

But just as the community appeared to be turning a corner, word of an unexpected obstacle arrived. Beyond the lingering toxic haze that blankets River Rouge, some 500 miles away in the nation’s capital, a scheme was in motion at the Department of Justice (DOJ) to undermine the agreement.

Trump appointees at the DOJ were plotting to stand between the residents of River Rouge and the benefits they fought for a decade to secure. Their success would have marked a dangerous precedent that threatened environmental progress not only in River Rouge, but also in every polluted community in the country.

Knowing how far-reaching the devastation of an unfavorable decision could be, Sierra Club contacted Earthjustice to ready a legal challenge.

River Rouge has experienced the same kind of economic declines of other industrial towns across the nation: job losses, weaker unions, and an exodus of young people who grow up there and never return. In 2018, according to census data, per capita income in River Rouge was about $15,250.

The local economy has been sapped over the decades since Dobbins’ family first arrived. “Now, there are no grocery stores or banks,” Dobbins says. “And no hospital.”

For Dobbins, a study showing that River Rouge was one of the most polluted areas in Michigan was a wake-up call. It revealed that people in her community were dying at higher rates than elsewhere. Seven years ago, she joined the Michigan chapter of the Sierra Club hoping to make a difference.

There she volunteered alongside Deitra Covington, who had joined after attending a toxic tour led by the Sierra Club. Covington was shocked to find that her hometown was part of the tour.

Covington, 48, was a school administrator born and raised in River Rouge. “I was very surprised that I had been living in this situation,” she says. “We knew the [industrial] plants existed, because our parents worked there, but not the fact that it was toxic to our health.”

Covington had seen many children suffering from asthma and missing school because of it. “Some had failing grades because of absenteeism. I saw it constantly,” she recalls. River Rouge isn’t the only place where air pollution is affecting student performance. In cities across the nation, researchers are finding that children who live near toxic release sites and even major highways — disproportionately children of color — are more likely to struggle academically.

After taking the toxic tour, Covington began holding events to educate the community. She also became active with the Sierra Club, becoming the first Black member of the Michigan chapter’s executive leadership team.

The River Rouge Covington grew up in was, and still is, a town where Black and White people for the most part lived in separate communities.

“Racism existed and exists in River Rouge,” Covington says. “We had a Black side and a White side. We would say I live on the Black side or I live on the White side.” Now, she says, some Black people have moved to the White section of River Rouge, but no White people have moved to the Black side. The percentage of White residents has decreased overall.

Covington is aware of the disparate pollution impacts on communities of color, but in River Rouge, she says the pollution affects everyone: “There’s no wall keeping pollution out of some communities.”

This spring, Dobbins had her own health scare that she suspected was linked to industrial pollution. She survived a bout with COVID- 19, including a couple of weeks in intensive care. Dobbins wonders whether toxic air made her illness worse, as research suggests it can.

After making a full recovery and returning home from the hospital, Dobbins continued to fight for clean air in her community. She and Covington participated in the legal negotiations with DTE to protect the community’s interests and ensure a cleaner, healthier future.

The $7.5 million offer was made by DTE to settle a case opened in 2010, which the Sierra Club later joined with legal representation from Earthjustice. The settlement was not unlike so many others that have been reached over the decades, when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has found that a community has been harmed and has supported or allowed remedies.

The case alleged that DTE violated the federal Clean Air Act by failing to install modern pollution controls on one of its coal-fired units, thus needlessly exposing nearby residents to high levels of toxic chemicals linked to premature death, worsened heart disease, aggravated asthma, and other respiratory illnesses. In 2013, the Sierra Club and the federal government added to the case similar claims against four other DTE coal units.

In May 2020, the federal government reached an agreement with DTE that the Sierra Club signed on to. A separate agreement between the Sierra Club and DTE would provide for additional environmental benefits, including electric buses and other air quality improvement measures. The settlement would conclude a decade-long court battle, and the community could finally claim victory.

This is a threat to the enforcement of environmental laws...

Shannon Fisk

Director of State Electric Sector Advocacy, Earthjustice

Even DTE celebrated the moment. In a press statement, Skiles Boyd, DTE’s vice president of environmental resources and management, said: “We want to thank the EPA and the Sierra Club for working with us. This action by all parties will further improve the quality of life for residents of Wayne County.”

The DOJ, however, made it clear they did not share the same amicable view. Federal attorneys filed an objection in July 2020, urging the court to reject the separate agreement between the Sierra Club and DTE. Their filing argued that a community group or individual cannot settle a Clean Air Act lawsuit for relief beyond what the federal government is willing to approve.

On the surface, the DOJ petition appeared to be run-of-the-mill procedural wrangling. However, according to Earthjustice attorney Shannon Fisk, it was an unprecedented action that would have reverberated across the country.

“This is a big fight, and we need to win,” Fisk said when this story was first reported in fall 2020. “This DOJ wants to obliterate the public’s ability to use federal actions to ensure that environmental benefits go to communities that have been harmed by industry. This is a threat to the enforcement of environmental laws, as well as our ability to use those laws to advance environmental justice and address environmental racism.”

The DOJ’s meddling in this private settlement reflected a radical interpretation of the U.S. Constitution — a view that only the executive branch should decide how to enforce our nation’s environmental laws. If accepted by the courts, these positions would have overruled the ability of every American community to use federal laws to protect themselves from pollution.

“I find it unconscionable that the DOJ would object to an overburdened community receiving air quality improvements,” Fisk said. He explained that the department’s action threatened to weaken an important tool Congress has given to the public to advocate for themselves in courts of law. “It’s a slap in the face to residents seeking redress for harms to their health and environment. This is especially true for low-income communities of color like River Rouge.”

In August 2020, Earthjustice filed a response on behalf of the Sierra Club challenging the DOJ position. The brief laid out the case that the Sierra Club-DTE agreement advances the Clean Air Act goal of improving air quality. It also cited numerous cases in which courts have rejected the very arguments the DOJ is now making to attack the agreement.

Covington found the DOJ’s objection reprehensible. “I feel it’s totally appalling,” she said, also expressing that she wasn’t surprised.

Dobbins was frustrated that the federal government presumed to know what’s best for the residents of River Rouge while at the same time denying them their hard-won benefits. “How are you going to tell us how to keep our kids safe while objecting to electric buses — something that’s going to save people?”

Both women were resolved to continue fighting for their community, and so was Earthjustice. As 2020 drew to a close, the court announced its decision, ruling against the Trump administration and bringing the 10-year battle to its just conclusion.

In February 2021, the Biden administration Department of Justice decided not to appeal the case. That same month, Dobbins and Covington both received awards from the Michigan chapter of the Sierra Club for their work to protect the state's environment.

Though this fight is finally behind them, the women recognize that there are still battles ahead to rebuild their community. But they’re encouraged by the strength and resilience of the leadership that’s emerging around them. “We’ve got a new group of fighters,” says Dobbins. “We’re not going to back down. We’re not going to go away.”

Earthjustice’s Clean Energy Program uses the power of the law and the strength of partnership to accelerate the transition to 100% clean energy.

Shannon Fisk is the director of State Electric Sector Advocacy. Prior to his current role, he served as managing attorney for the Coal Program, and led Earthjustice in pushing the nation to become less dependent on its aging coal fleet, stopping uneconomic investments in dirty power plants, and making way for untapped renewable energy resources and innovation in energy efficiency.

Keith Rushing, Earthjustice’s national communications strategist for Justice & Partnership Storytelling, is a communications professional with a passion for social justice issues. @krush526

Maz Ali, was a managing editor at Earthjustice, who wanted to popularize stories and information we can all use to protect our communities and safeguard the natural world.