‘Virtual’ Hearings Are Silencing Indigenous Voices in Alaska

Amidst COVID-19, Trump administration asks Alaska Native communities to log on Zoom and talk about the destruction of their ancestral lands.

This page was published 5 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

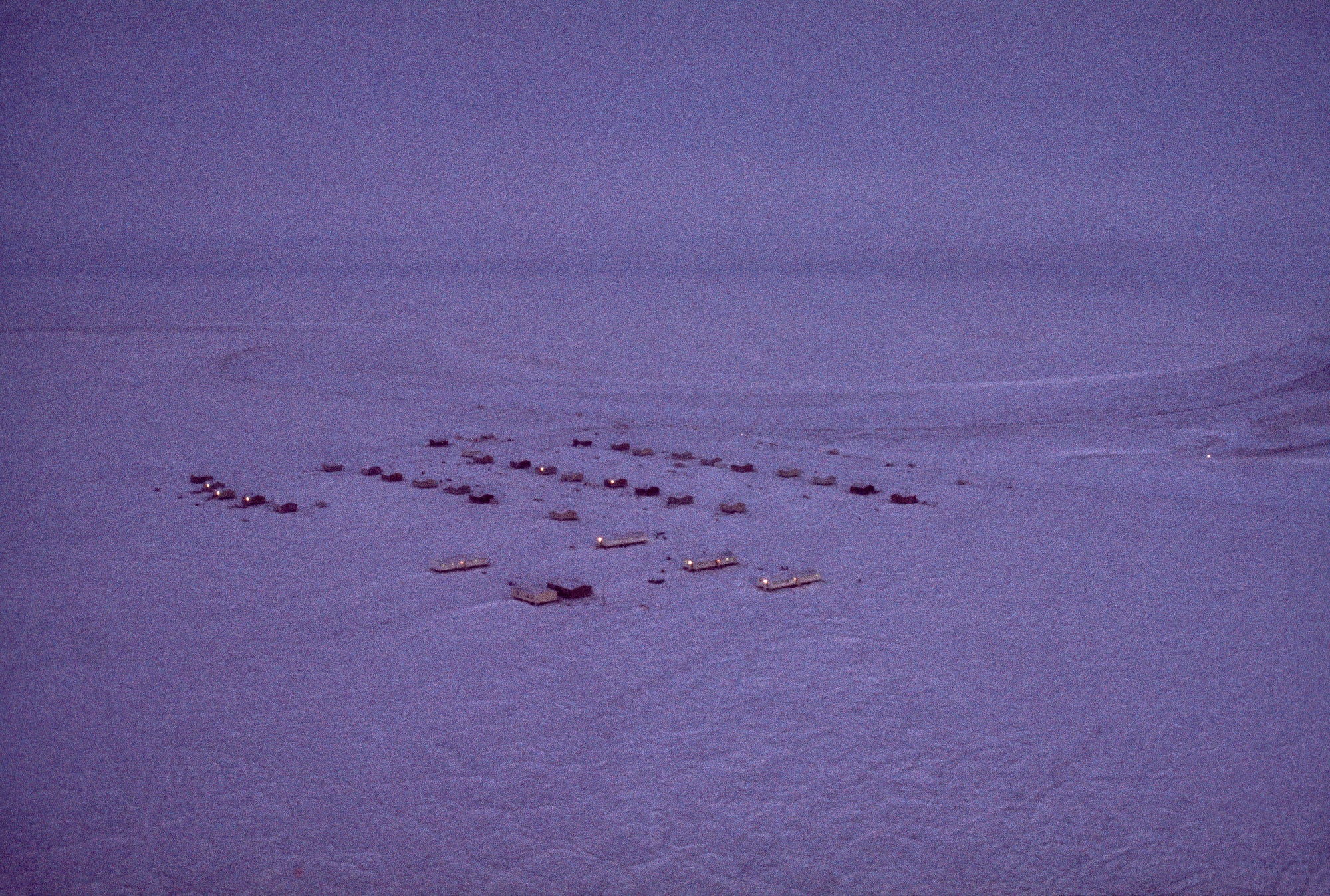

Zoom video conferencing has skyrocketed in popularity since the pandemic forced millions to devise new strategies for socializing — but in Nuiqsut, a tiny Alaska Native village where wild caribou meat is a mainstay, some residents were outraged after a Zoom encounter with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Throughout April, in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic, BLM held “virtual” public hearings to gather input on ConocoPhillips’ Willow Project, a massive oil-and-gas drilling plan that will transform a vast expanse of Arctic tundra into a sacrifice zone for industry. Earthjustice is representing Nuiqsut in litigation against other ConocoPhillips oil and gas development in the region.

The oil company’s vision — featuring 50 new oil wells, pipelines, a gravel mine, a network of roads, a lit airstrip, and a temporary offshore island — poses hardship for a community that lives off the land and relies upon traditional hunting practices to sustain themselves. Nor did Nuiqsut residents feel BLM took their concerns seriously during the virtual hearing.

“I myself was muted after my initial comment,” resident Martha Itta wrote in a letter to BLM following the virtual public hearing, “and they would not unmute me.”

Itta was sheltering in place when she logged onto the hearing, which went forward by phone and video conference despite formal requests for postponement, since remote villages were already scrambling to deal with the COVID-19 crisis.

The federal government is legally required to give citizens a chance to weigh in on decisions that meaningfully affect their environment. But Nuiqsut is just one of a growing number of communities that have struggled to be heard as the Trump administration plows ahead with remote public hearings at a time when many people are sick, caring for family members, or otherwise limited in their ability to participate in virtual meetings.

The problem isn’t limited to Alaska. In early April, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) held a phone-in hearing on a proposal to weaken national standards that protect people from toxic coal ash. Earthjustice sent a letter on behalf of more than 60 public-interest groups to the EPA, calling for genuine, in-person hearings after the pandemic crisis has passed. (In certain specific circumstances where communities have requested online hearings, Earthjustice supports their wishes.)

But the government’s decision to press ahead with controversial extractive industry projects in the middle of a pandemic presents unique challenges for Alaska Native communities, and stings in unique ways.

“Alaska Native peoples have survived past pandemics, and COVID-19 recalls the 1918 flu that caused near genocide of our peoples,” Siqiniq Maupin, whose family is from Nuiqsut, wrote in an opinion piece for the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. “The impact and trauma of that pandemic is remembered by many as though it were not so long ago.”

Despite the requests for a delay and the often unreliable, or completely inaccessible, internet connections in this remote polar region, BLM pressed ahead with the virtual hearings anyway, all while oil prices sank to astonishing lows in the background. This meant everyone from elderly grandmothers to parents of small children had to participate virtually if they wanted a say — something not everyone could do.

“We told BLM that many people who wanted to comment could not, because they did not have the proper technology,” Itta explained in her letter to BLM.

Hundreds of miles away, in southeast Alaska — where patches of old-growth temperate rainforest lie speckled across misty islands — another native village is experiencing similar frustrations. In this case, the U.S. Forest Service is barreling ahead with plans to lift logging restrictions in the surrounding Tongass National Forest.

Joel Jackson, president of the Organized Village of Kake (pronounced like “cake”), says his days have been consumed with hours of teleconference calls since the start of the global pandemic. Even though he must the conduct the official business of his tribal government, he sometimes experiences internet slowdowns that make it impossible to log on.

The most pressing issue on Jackson’s mind is petitioning subsistence regulators to allow Kake to carry out an emergency moose and deer hunt, since stores in Kake have had trouble keeping their shelves stocked during the pandemic.

“Right now, we’re experiencing a lack of fresh meat coming in, and also other food products,” Jackson explained in a May 1 interview. He added that people need traditional wild foods from the surrounding Tongass, to boost their immune systems.

Yet even as his village grapples with this crisis, U.S. Forest Service officials are asking his tribal government and others to participate in virtual meetings over plans to lift Tongass logging restrictions, by eliminating the 2001 Roadless Rule that currently prevents logging and roadbuilding there.

Government-to-government consultations are mandatory when government actions affect Tribal interests, normally held in person to respect tribal sovereignty and ensure effective communication. Gutting the Roadless Rule would open the old-growth rainforest up to clear-cuts, directly affecting the lives of people in Kake and other communities where hunting, fishing, and wild food harvesting are a way of life.

In a letter from Kake and other Southeast Tribes to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the Forest Service, tribal leaders explained why virtual meetings were not feasible.

“COVID-19 has disrupted normal working, schooling, and living conditions, impairing the ability of many parents, elders, and members of the general public to go about their daily routines, much less weigh in on Forest Service actions that affect us,” the letter said. “Many tribal communities have limited Internet bandwidth to participate in virtual meetings. Further, in some communities, participating in virtual meetings requires community members to gather in a single location where reliable internet is available,” something that could be very dangerous during the pandemic.

“We want them to put off the final decision until after everything is over,” Jackson explained. Earthjustice and other organizations working to protect the Tongass echoed calls for a delay in a follow-up letter to the Secretary of Agriculture.

The rest of the world’s plans are on hold in the face of the coronavirus crisis. Nevertheless, the Forest Service, like BLM, has given no indication that it will slow down with plans to hand over public lands to extractive industry, even if it means silencing the voices of indigenous communities in the process.

Opened in 1978, our Alaska regional office works to safeguard public lands, waters, and wildlife from destructive oil and gas drilling, mining, and logging, and to protect the region's marine and coastal ecosystems.