Brown v. Board of Education and the Fight for Real Justice

The landmark case speaks to why well-funded and insidious interests continue trying to shut the people out of the courtroom.

Last week marked the 65th anniversary of Oliver Brown et. al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, which was a landmark case that shook the foundation of legalized segregation in the South. It is a challenging time to celebrate such an anniversary, as deep, structural inequities and social marginalizations persist along lines of race, gender, national origin, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status, not to mention the democratic decay that slides us farther and farther from the ideal world we wish to see. Indeed, some of this backsliding is personified in the countless judicial nominees emanating from the Trump administration who refuse to admit that Brown v. Board was even rightly decided.

It’s exactly at moments like these when we need to lean ever more deeply into the struggles and histories that tell us how we grew beyond our self-perceived limits as a society, and how we must continue to grow. These stories show us how brilliance and intellect shone in even the bleakest of conditions. How the laws built to serve as weapons of power were transformed by the oppressed. Brown v. Board set the stage for generations of legal and legislative progress towards the safe, healthy, equal, and sustainable communities for all. Progress that is now under threat.

Brown v. Board is exactly the kind of case that speaks to why well-funded and insidious interests want to shut the people out of the courtroom. In fact, some of the over 70 legislative attacks on access to justice Earthjustice tracked in the last Congress alone would have made it harder to bring the case. This is a fight we must continue to wage.

The “Equalization” Legal Strategy Informing Brown v. Board

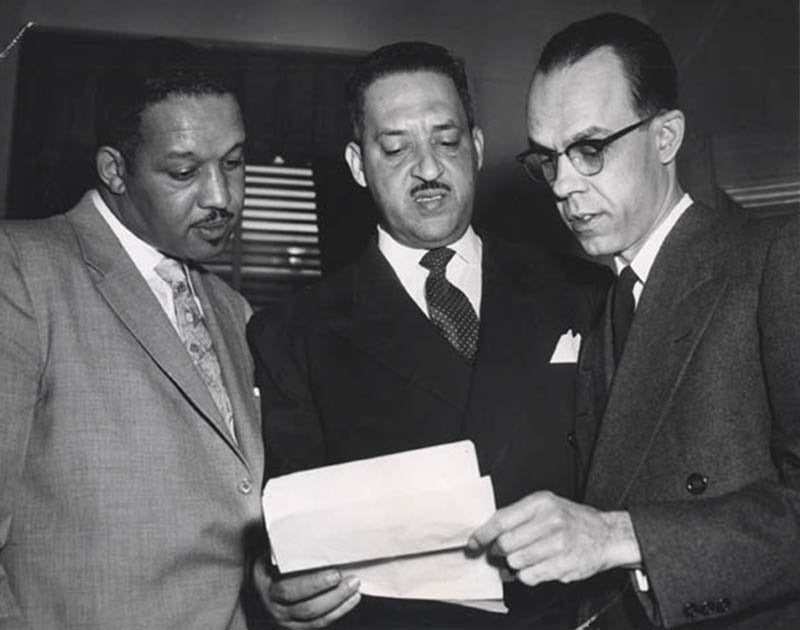

For good reason, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is proud of the legal strategy that paved the way for Brown v. Board. The case was the culmination of a half-century of focused legal work performed by some of the top Black legal minds in the country. Almost immediately after the turn of the century and Plessy v. Ferguson, lawyers were assembling to consider avenues to fight back against legally sanctioned discrimination in the courts. By the 1930s, studies demonstrating that contrary to Plessy’s holding, facilities for African Americans were separate but never equal. This led to a focused series of lawsuits aimed at remedying core imbalances. Into the breach stepped groundbreaking Black legal minds who were and remain among the greatest figures in the history of our nation’s judicial system: Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall, and Nathan Margold.

“A lawyer is either a social engineer or a parasite on society,” Houston, the first dean of Howard University Law School said. Houston and others aforementioned were undoubtedly the former. In the first half of the twentieth century, Houston molded a strategy developed by Margold, called the “equalization” strategy. This was a strategy that sought to focus a campaign of litigation against inequities in major components of life in the United States. Houston narrowed the focus to hone in on educational inequities instead of attacking segregation along a broad front. He knew, as so many people did, that the realities of segregation meant that separate facilities were far from equal — and that the costs of raising the standards of Black educational institutions to those of White ones would prove prohibitive for many states. With a series of tactical lawsuits, Houston would either win cases or prove the law itself to be a farce. He won, and by winning, opened the door for a young student to walk through and break even more barriers.

The Plaintiffs, the Attorneys, and the Road to Brown v. Board

Thurgood Marshall commuted from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. for three years while pursuing his legal education at Howard University under Houston. Marshall’s mother sold off her wedding and engagement rings to help him obtain an education, and he did not disappoint her, graduating close to the top of his class. His first legal victory was just a year after he graduated law school, in a case on behalf of Donald Gaines Murray. Both Murray and Marshall were denied entry into the University of Maryland Law School. Marshall filed a case against Maryland on Murray’s behalf and won. In case after case, Marshall built upon the legacies of Houston, Margold, and others who came before in demonstrating the effectiveness of the law as a force for equity and the common good. He won his first case before the United States Supreme Court at the age of thirty-two, a case demonstrating that a confession resulting from police pressure violates the Due Process clause. In time, Marshall trained his focus on the task of dismantling Plessy v. Ferguson itself.

Legal briefs from Brown v. Board of Education

Image Courtesy of Library of Congress

Many do not remember that Oliver Brown et. al. v. Board of Education of Topeka was, in fact, the result of a consolidation of several cases in far-flung regions of the country. Brown’s choice as the head of the client roster reflected contemporary opinions that having a man at the center of the field would enhance the chances of success in the case. Brown’s is far from the only story: Barbara Rose Johns started a student protest after becoming fed up with deplorable conditions at her high school where students had to attend class in school buses because the school was at double capacity. As a child, Harry Briggs had to walk five miles to a small wooden school where he and other students had to chop wood when the coal ran out. Both of them became plaintiffs in suits that folded into the landmark case, along with plaintiffs from class action suits in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. While one person’s experience alone was not viable for a win, taken together — these plaintiffs showed how deeply entrenched inequity is in segregation.

A Fight Just Beginning

The story so many of us know — the 9-0 ruling at the U.S. Supreme Court holding that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate, but equal’ has no place” because “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” — was in many ways only the beginning, and it has yet to come to an end. The Jim Crow South had its fair share of judges who exploited nuances of the law to maintain the segregation status quo and attempted to shut out those who would seek equality outside of the courthouse. It was the continued, relentless efforts of civil rights activists and public interest litigants that helped spur changes to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to expand class actions and kept the courtroom doors open for all. When legislatures passed racially divisive laws post-Brown that didn’t mention race, “Southern courts prevented [African-Americans] from bringing class actions, saying that, because the laws did not mention race, collective action was impermissible.” Later efforts expanded the definition of what could be brought as a class action lawsuit.

As it was in the days of Brown v. Board, there remains an inherent tension among advocates for justice between litigation strategies and civil disobedience actions. The two have always lived side by side, and in many ways cannot do without each other. With battles in the courts serving as extensions of marches in the streets, changes to public discourse and understanding helped inform changes to the law. Indeed, Brown v. Board was the first case to make use of a Brandeis brief with scientific and sociological evidence demonstrating the harm segregated schools caused to young Black minds — and continue to do so today. Just as it was then, too, the forces of reaction and repression are leveraging every tool they have to try to block us from the courts, with over 70 legislative attacks on access to justice in the last Congress alone. Some would limit the public’s ability to get into court. Others would restrict class actions. All of them would make access to justice an unobtainable fairytale.

We cannot overstate the threat posed by those who would ignore this history and shrug their shoulders at one of the landmark cases of American jurisprudence. The fight for access to the courts is an extension of the fight for people’s lives. Earthjustice and our partners will remain firm against the conflicted judges and corporate special interests who would stand against it.

Established in 1989, Earthjustice's Policy & Legislation team works with champions in Congress to craft legislation that supports and extends our legal gains.

Earthjustice Media Relations Team

media@earthjustice.org