Wyoming Court Decision Helps Provide Access to Over 8 Million Acres of Public Land

Court rules that “corner-crossing” does not constitute trespass.

Update: As expected, Iron Bar Holdings appealed the district court’s decision to the Tenth Circuit. Iron Bar continues to assert that the four Missouri hunters trespassed when they stepped from public land to public land at shared corners in the checkerboard because they passed momentarily through private airspace. Iron Bar’s briefing makes clear that the true purpose of its lawsuit is to claim public land for itself, arguing that the district court’s ruling would cost private landowners “billions” of dollars in property value — by eliminating their exclusive access to public land.

To push back on that absurd and unjust claim, Earthjustice filed an amicus brief in support of the hunters, on behalf of four conservation and environmental justice groups: Great Old Broads for Wilderness, GreenLatinos, Sierra Club and its Wyoming Chapter, and Western Watersheds Project. The amicus brief describes how Iron Bar’s lawsuit is part of a larger problem in the West, in which private landowners use tactics like misleading signage, threats, and even violence to exclude members of the public from public land, with disproportionate impacts to women, communities of color, and immigrant communities.

The brief explains that the federal Unlawful Inclosures Act and fundamental principles of trespass law grant the public a right of reasonable access to public land in the checkerboard, undermining Iron Bar’s claim. The bottom line is that allowing the public to step over common corners (and through a few inches of private airspace) is a far more reasonable outcome than allowing wealthy, private landowners to take millions of acres of public land for themselves. We now await a decision from the Tenth Circuit.

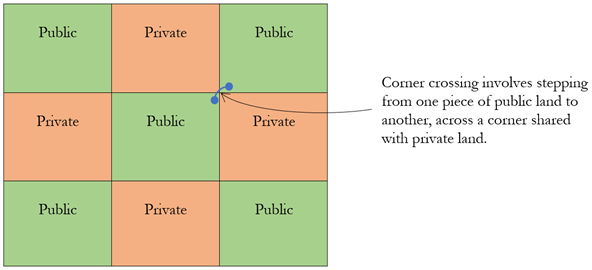

In a major win for public land users, a federal court ruled that the act of “corner-crossing” — stepping from one piece of public land to another over a corner shared with private land — does not constitute trespass. The decision could help provide access to over 8 million acres of public land.

Corner-crossing is a big deal in the West because a lot of public land is surrounded on four sides by private parcels. The basic unit of land ownership is a square-mile (640-acre) block called a “section.” Due largely to a 19th-century law aimed at promoting development along railroad corridors, land in the West is often arranged in a checkerboard pattern, with alternating sections of public and private parcels, as shown below. Because of this checkerboard, a lot of public land is “corner-locked,” meaning no public road or trail provides direct access, and it touches other public land only at the corners.

Because the legality of corner-crossing has long been ambiguous, these corner-locked public lands have generally been inaccessible to the public. The most detailed, comprehensive report on this issue found that 8.3 million acres — an area nearly four times the size of Yellowstone National Park — across 11 Western states are corner-locked. As a result, the public has long been deprived of access to land it owns.

In 2020, and again in 2021, four big-game hunters decided to access public land near Elk Mountain in Wyoming by corner-crossing. The private land that shares the corners is part of Elk Mountain Ranch, which is owned by Iron Bar Holdings, LLC, the North Carolina-based company of multi-millionaire Fred Eshelman, who made his 9-figure net worth in the pharmaceutical industry.

Under pressure from Eshelman and his local ranch manager, Wyoming prosecutors charged the four hunters with criminal trespass. They were acquitted by a jury in early 2022. Undeterred, Eshelman sued the hunters for civil trespass violations, claiming that the hunters momentarily passing through the airspace at the common corners caused him over $7 million in damages.

On May 26, 2023, the U.S. District Court for the District of Wyoming rejected Eshelman’s claims. Relying largely on a century-old decision involving sheep grazing, the court determined that, “where a person corner crosses on foot within the checkerboard from public land to public land without touching the surface of private land and without damaging private property, there is no liability for trespass.” Central to the court’s reasoning was its observation that, in the unusual circumstance checkerboard land ownership presents, a private landowner “cannot secure for itself” the value of public land interspersed within private property while “cast[ing] upon the government and [the public] all the disadvantages of the interlocking arrangement.” Instead, the court determined that “the private landowner is entitled to protect privately-owned land from intrusion to the surface and privately-owned property from damage while the public is entitled its reasonable way of passage to access public land.”

Applying these principles to the hunters’ activity, the court held that the hunters had not trespassed by stepping from one corner to another, without ever touching private land. Significantly, the court also found that the hunters had not trespassed at one corner where Eshelman’s employees had installed two posts and a chain designed to block access across the corner and the hunters had grabbed the posts to swing around them. Instead, the court found that the ranch’s post-and-chain blockade violated the federal Unlawful Inclosures Act of 1885 because it was “an improper attempt to ‘prevent or obstruct . . . any person from peaceably entering upon . . . any tract of public land.’” Because the post-and-chain obstruction was illegal, Eshelman could not claim legal harm from the hunters circumventing it. Thus, each instance of corner-crossing was deemed legal.

The court’s decision is a significant, positive development for public land users across the West. The decision is grounded in the common-sense principle that private ownership rights are not unlimited and must, in some cases, yield to the public’s right to access public lands. While the court observed that its holding was “unique to and limited in application to the peculiar interlocking arrangement of odd and even numbered sections making up the checkerboard pattern of land ownership created by Congress in the mid-1800s,” the decision makes it harder for private landowners to block access to millions of acres of corner-locked federal public lands.

The next step is ensuring that this victory remains the law of the land. Defending the district court’s decision is therefore imperative. While Earthjustice was not involved in the district court case, we will be monitoring the Tenth Circuit proceedings and, as appropriate, may help groups weigh in to support public access. A positive outcome is more likely as more voices add to the chorus: our public lands are for all to enjoy, not just the privileged few.

To learn more about this issue, visit Backcountry Hunters and Anglers.

Earthjustice’s Rocky Mountain office protects the region’s iconic public lands, wildlife species, and precious water resources; defends Tribes and disparately impacted communities fighting to live in a healthy environment; and works to accelerate the region’s transition to 100% clean energy.

Perry Wheeler

Public Affairs and Communications Strategist, Earthjustice

pwheeler@earthjustice.org