Removing Four Dams Could Save These Wild Salmon from Extinction

Hang around salmon advocates long enough, and sooner or later you’ll hear someone describe the fish as “magical.”

This may sound hyperbolic, especially for a fish most people associate with dinner, but consider the remarkable ability of salmon.

After completing the long journey from freshwater streams to the ocean, salmon must survive several years in a perilous saltwater habitat, dodging killer whales and other predators.

When it’s time to return to their spawning grounds, they migrate upstream along fast-moving mountain rivers, often for hundreds of miles and climbing thousands of feet in elevation to the precise location of their birth.

The fish have completed this migratory cycle for millennia, demonstrating resilience through forest fires, volcanic eruptions and ice ages.

Yet the biggest threat to their survival is not an act of nature. It’s man-made dams — which create barriers to salmon migration to and from the ocean.

The Pacific Northwest’s Columbia River basin was once one of the greatest salmon-producing river systems in the world. Now it is among the most heavily dammed river systems.

Four dams on the lower Snake River — Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose, and Lower Granite — are especially harmful, impeding salmon’s passage through an essential migration corridor that joins with the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean downstream and flows out of millions of acres of wilderness in Idaho, Washington, and Oregon upstream.

As long as these dams remain in place, salmon and steelhead migrating along this route will languish on the brink of extinction.

Dismantling those dams would set in motion one of the greatest river restorations ever, opening free-flowing access to some 5,500 miles of pristine salmon-spawning habitat, the best remaining salmon incubator in the lower 48 states and one that will remain relatively cool and productive even as the climate warms.

In 2016 and 2017, more than a quarter million people sent comments to federal agencies that oversee hydropower operations calling for their removal. Following an Earthjustice lawsuit, a court mandated that the agencies draft a new plan for operations to aid the endangered fish.

Editor's Note:

Earthjustice, in coordination with partners, is engaging with congressional leaders and the Biden administration to authorize removal of four dams on the lower Snake River. With the federal government finally poised to take action as well, we have temporarily paused litigation to seek a comprehensive solution.

Unfortunately, on Feb. 28, 2020, the agencies produced a draft plan that delivered little in the way of substantive solutions to prevent salmon extinction.

But there is new reason to be hopeful. By July 2022, Washington’s Senator Patty Murray and Governor Jay Inslee are expected to release an actionable plan for removing the dams and replacing their services.

And, the White House Council on Environmental Quality Chair Brenda Mallory, Interior Secretary Haaland, and other administration leaders announced a multi-agency commitment to identify a path forward that honors longstanding commitments to Tribes while supporting economic growth, restoring ecosystem health, and ensuring a clean energy future.

As part of their consultation with Northwest Tribes, these leaders reaffirmed their commitment to bold, new action to restore wild salmon in a joint White House press statement.

Tribes, communities, and families across the region are ready to be a part of this effort and are counting on leadership from the Biden administration.

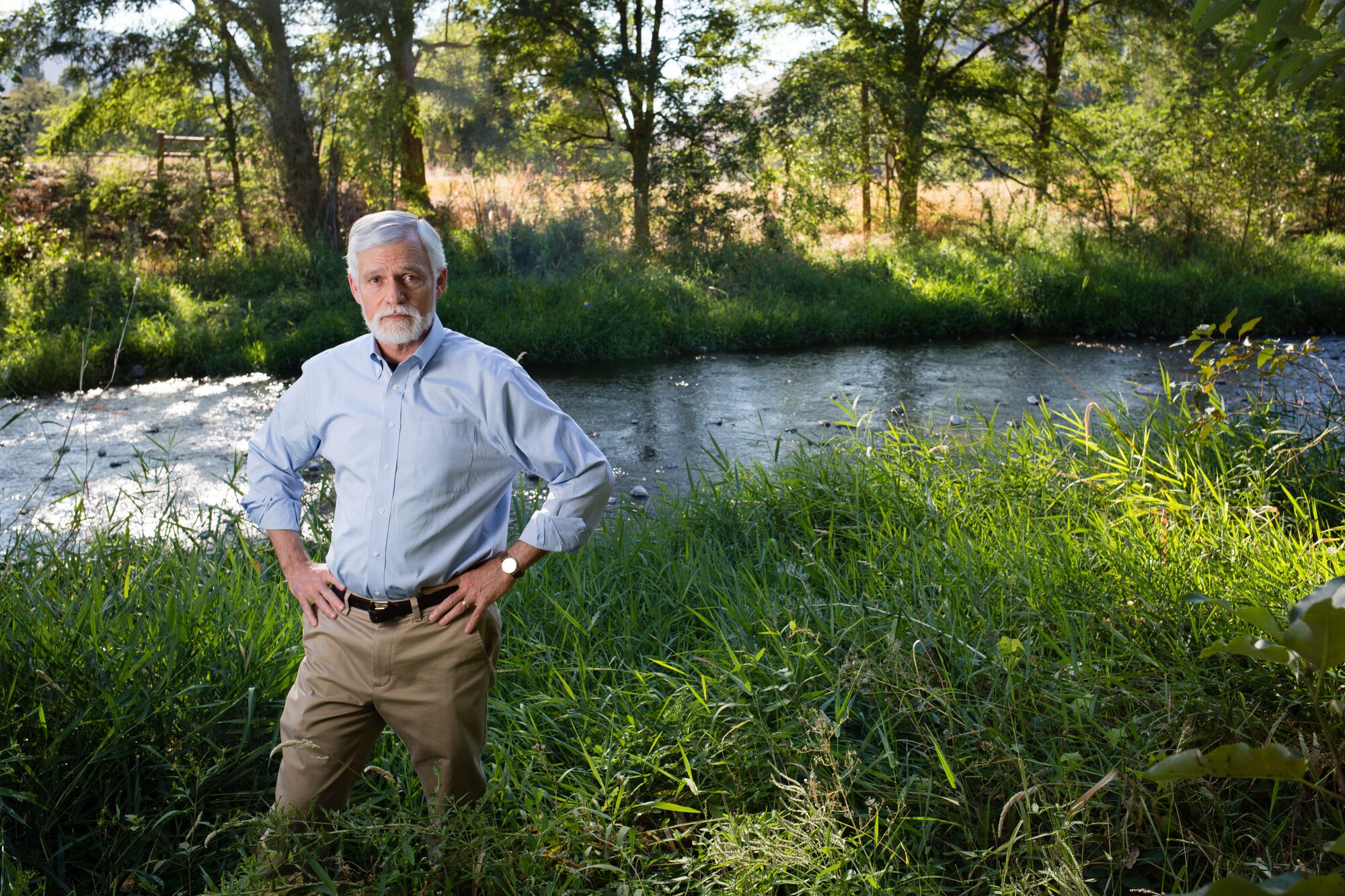

Todd True

Senior Attorney, Earthjustice

Todd True

Senior Attorney, Earthjustice

"We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to restore the lower Snake River and bring back salmon,” says Todd True, an Earthjustice attorney who has been working to protect wild salmon for more than two decades.

Inside the Legal Case

Earthjustice attorney Todd True explains why the removal of four Snake River dams is a necessary and feasible action to save wild salmon.

He adds that now is the ideal time to make the push to replace the dams with carbon-free, clean energy.

The real question is how long we will put up with wasting tax dollars on increasingly irrelevant dams.

“We have an opportunity here to do right not just for salmon and taxpayers, but also for the Pacific Northwest, for everyone with an interest in the river, and for Native American Tribes for whom salmon are so culturally important.”

Rebecca Miles

Nez Perce Tribe Member

Rebecca Miles

Nex Perce Tribe Member

Salmon in the Columbia and Snake Rivers were once so plentiful that locals looked to them as a free, dependable food source. Rebecca Miles, a Nez Perce Tribe member, grew up catching salmon and has spent years fighting to restore endangered stocks in the rivers where her family fished for generations.

“We were poor, and the only way we were able to sustain our way of life was to hunt and fish,” she explains.

But as dams were built throughout the Pacific Northwest — all told, more than 400 dams span the Columbia River Basin — wild stocks fell into steep decline and many disappeared altogether.

Today, 13 of the surviving salmon and steelhead species in the basin have landed on the federal endangered species list, including all four of the remaining species of Snake River salmon and steelhead.

The four dams on the lower Snake River have proven to be especially destructive for these four species.

When a canoe is more than a canoe

For thousands of years, the Nimiipuu people piloted their canoes along the tumbling waters of the Snake River. But after dams were built and the river choked off, a tradition was lost for over 100 years. Until now.

For the Nez Perce, disappearing salmon runs translated into reduced dietary options and an erosion of cultural practices, such as preparing salmon for traditional meals.

Native American tribes such as the Nez Perce were guaranteed permanent access to customary hunting and fishing grounds in treaties signed by the U.S. government more than 150 years ago. Without the fish, such promises are rendered meaningless.

“Salmon are the lifeblood of our people. We cannot be who we are without fish,” Miles says.

Steve Pettit

Retired Biologist

Steve Pettit

Retired Biologist

Before the Lower Snake River dams were built, Steve Pettit, a now-retired Idaho Department of Fish and Game biologist, had a lunchtime ritual of fishing for steelhead near the confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers in downtown Lewiston. Stocks were so plentiful that it took little time to hook one among the rapids.

But Lower Granite Dam, the last of the four to be completed just across the border in neighboring Washington, brought a permanent change to the river. As the reservoir filled behind the dam in 1975, Pettit watched as his babbling fishing spot transformed into a flat, glassy pool.

“In the saddest day of my life, I watched it go under,” he says, remembering that he was out on a jet boat that day. “The river got silent.”

In the decades that followed, Pettit — whose job entailed tracking fish health — watched salmon and steelhead populations plummet. Asked what will become of the fish if the dams remain, he shakes his head.

“It’s only going to take two or three years of catastrophic summer conditions to put many types of [endangered] fish in Idaho in a precarious situation,” he says. “Some of them are barely holding on now.”

Sam Mace

Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition

Sam Mace

Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition

For decades, biologists like Pettit have pointed to removing the lower Snake River dams as the most effective protection measure for wild salmon. The outcome of recent dam removals on the Elwha River in Washington state’s Olympic Peninsula is proof that dam removal works — salmon there have rebounded even faster than scientists initially predicted.

But federal agencies have been as inflexible about the Snake River dams as the concrete that impedes the endangered species’ passage.

Despite multiple federal judges rejecting agencies’ past measures to revive wild salmon because the plans were inadequate, the feds have yet to take seriously the option of dam removal. Nevertheless, a broad coalition is working together to push for the one solution that could actually bring back wild salmon.

“The fish don’t have much time left for us to do something,” says Sam Mace, Inland Northwest Director of the Save Our Wild Salmon coalition, a wide-ranging partnership of fishing groups, conservation organizations and clean energy advocates, many of whom are represented by Earthjustice. “And the agencies have already taken too long.”

The tide is turning. Following the 2016 court victory that compelled the federal agencies to begin working on a new plan, a number of efforts have been underway to protect dwindling wild salmon in the Columbia and Snake rivers.

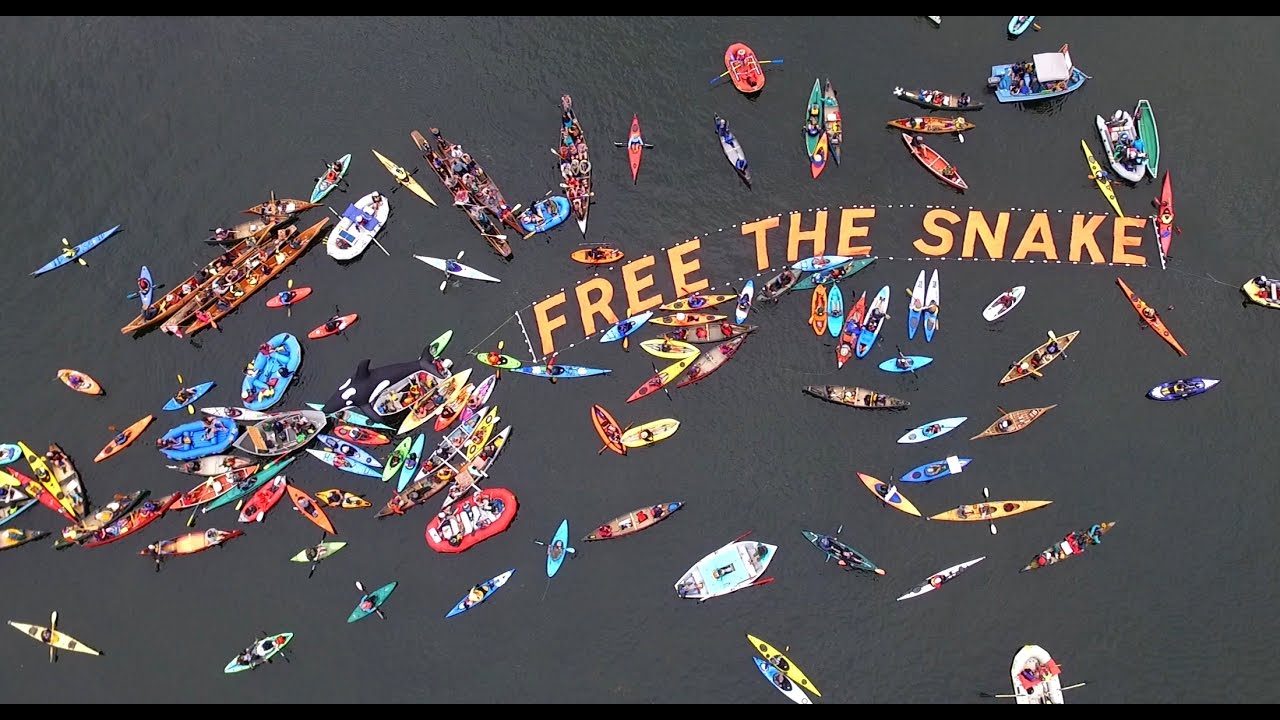

Annual rallies — dubbed the “Free the Snake Flotilla” — were held in the fall of 2015, 2016 and 2017, featuring hundreds of fishermen, kayakers and members of Pacific Northwest tribes paddling in traditional canoes.

An April 2018 report, meanwhile, outlined a detailed scenario that would offer Pacific Northwesterners affordable, reliable clean energy and healthy wild salmon populations. Energy Strategies, a company serving power producers and governments throughout North America, conducted the study on behalf of a coalition of conservation and consumer advocacy organizations called the NorthWest Energy Coalition.

The study found that the four dams aren’t necessary to power the region, since the electricity they generate could just as easily be supplied by a mix of renewable energy, efficiency and demand management.

This transition would come with a monthly cost increase of just $1.25 per household — mere pennies a day.

Another legal victory on Apr. 2, 2018, helped juvenile salmon gain at least some temporary protection while federal agencies contemplate long-term measures such as dam removal.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit — siding with almost a dozen conservation and fishing organizations, the Nez Perce Tribe, and the State of Oregon — upheld a U.S. District Court ruling that federal dam managers must allow more river water to flow over the dams in the spring months, to facilitate safe passage for young salmon migrating to the ocean.

Now leaders in the region are taking up the mantle. Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington created a task force to issue recommendations about how to save the endangered orcas. These orcas are starving and they depend on Chinook salmon from the Snake River at critical times of the year. But today there are too few salmon for them to eat. As part of Inslee’s orca task force, tribes, fishing communities, farmers, utilities, and other river users have gathered to discuss what they would need in order to make dam removal feasible.

Gov. Kate Brown of Oregon recently came out in support of this collaborative approach to solving the issue. Leaders in Idaho are trying to confront the extinction crisis as well.

Expanding these new conversations is the way forward for both salmon and orcas. Working together and with effective political leadership, we can solve the problems of salmon, clean energy, and prosperous rural communities.

The stakes are high. The impact of climate change has made river restoration all the more urgent. Salmon need cold water to survive, but dams have transformed ice-cold rushing rivers into slack-water reservoirs that bake in the sun. This stagnant environment is more likely to reach lethally hot temperatures due to global average temperature increases.

“After more than 20 years of federal failure, salmon are in desperate need of help now,” said Todd True, the Earthjustice attorney.

“It is time for all of us to work together to forge a comprehensive solution that restores abundant salmon, invests in communities, and ensures clean, affordable power into the future.”

Save wild salmon. You can help.

Originally published in the Earthjustice Quarterly Magazine.

Established in 1987, Earthjustice's Northwest Regional Office has been at the forefront of many of the most significant legal decisions safeguarding the Pacific Northwest’s imperiled species, ancient forests, and waterways.

Rebecca Bowe reports on the litigation docket of Earthjustice's lands, wildlife, and oceans work.

Chris Jordan-Bloch is a photographer and filmmaker for Earthjustice. He uses videos, photos, audio and words to tell the stories of Earthjustice and the people and places we fight to protect.