An Open Letter on DAPL

“Our experience is that the U.S. does not honor the treaties of their grandfathers,” writes the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s historic preservation officer.

This page was published 5 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

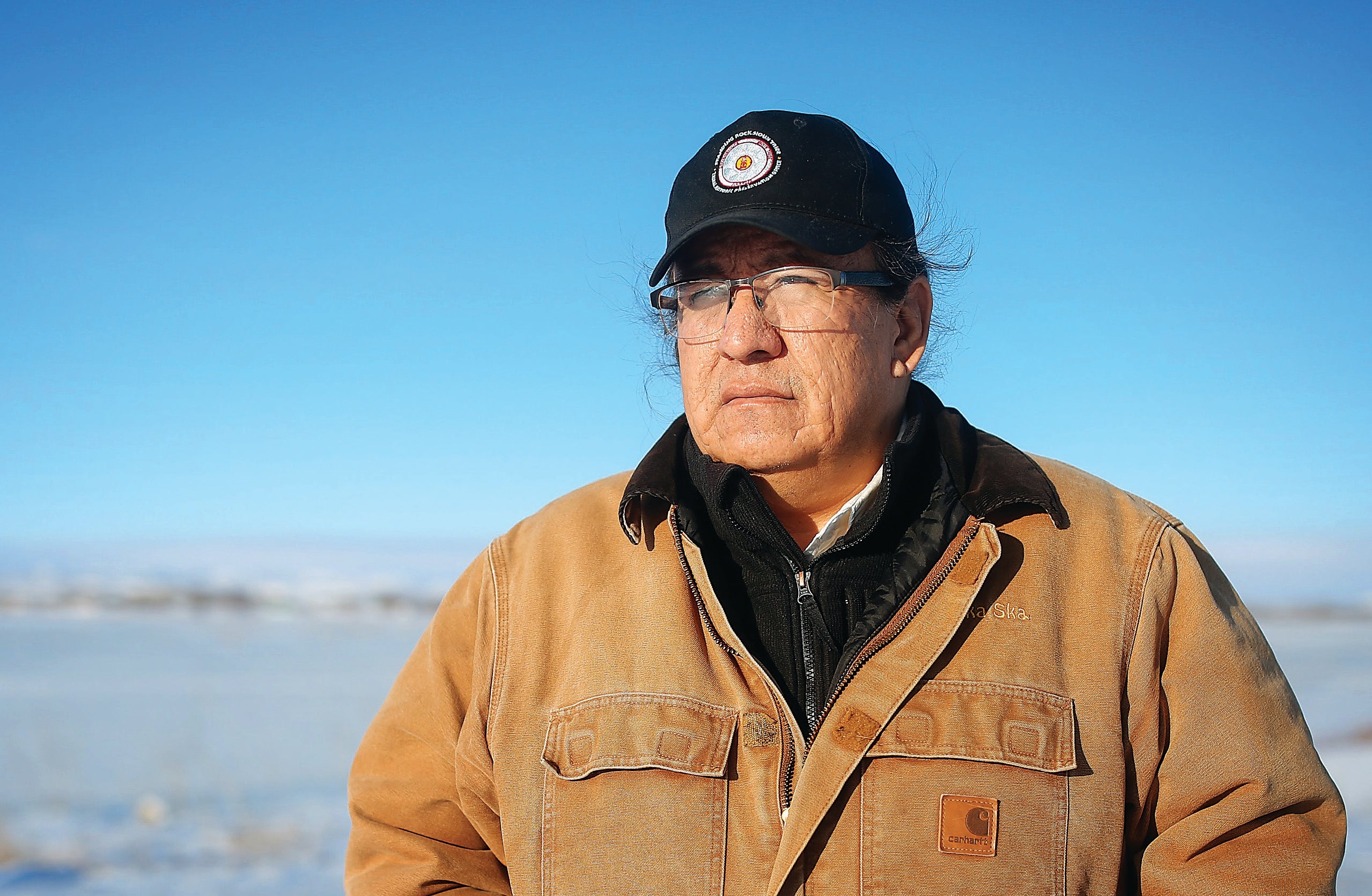

Jon Eagle Sr. is the historic preservation officer for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Earthjustice is representing the Tribe in its years-long effort to shut down the Dakota Access Pipeline, which threatens the Tribe’s lands. This statement was originally filed in federal district court.

Hau Mitakuyepi. Anpetu ki le, cante waste nape ciyuza pelo. Hehaka Ska imaciyapi, na wasicu eya Jon Eagle Sr., hemaca. Hunkpapa hemaca na canka ohkan tiospaye ematahan, na Wanbli Koyag Mani ematahan.

My relatives. Today I greet you with a good-hearted handshake. My Lakota name is White elk and my English name is Jon Eagle Sr. I am Hunkpapa and come from the Sore Back extended family, and the family of Walks Dressed in Eagle.

You may be wondering why I start in my language. In our belief system that is the most respect I can show you. To address you in one of the first languages spoken on this land. When you think of the wisdom of my ancestors and why our elders taught us to introduce ourselves in this way, it is so that as good relatives we are going to listen to each other. It also prepares us for times like today when we don’t agree with each other. If we look at each other as relatives we will always have that to fall back on.

I am the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO) for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and as I have stated in previous declarations, those four words — Standing Rock Sioux Tribe — do not accurately reflect who I really am. That’s who the United States government says I am. Every man, woman, and child enrolled at the Standing Rock Reservation has the same first three numbers in their enrollment numbers, 302. That is the Prisoner of War camp we come from. 302, a remnant of the Indian Wars.

I think it is important for you to understand that I do not look at myself as a victim. I am still standing on my own two feet, protecting my wife, and providing for my family. I also think it is important for you to understand that the world my family prepared me for no longer exists. I was taught how to live off the land, following ancient protocols that actually stimulate new growth. Never taking more than we need. And yet, in my lifetime I have witnessed changes to our natural environment that cause me to worry about my children and grandchildren. Will they be able to live off the land like I and everyone before me did?

Everywhere I go, I see sick or dying trees and I ask myself, “Where have the birds gone?” When I was a child, they used to blacken the sky. I see that deer and elk have wasting disease and we can no longer trust our food source. We are told not to let children and our elders eat too much fish because our rivers are polluted. There is no clean water anywhere in this country. What are we supposed to eat when they’re gone? The loss of the buffalo had a devastating effect on my ancestors that has been passed down the generations to us living today. It created a dependency that people in this country hold against us.

My ancestors signed treaties with the U.S. government in the hopes that their grandchildren would have a future. And yet our experience is that the United States does not honor the treaties of their grandfathers. Does our treaty not say, “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Indians herein named?” How is it that a pipeline could be allowed to go through our treaty territory without our consent? In fact, the environmental assessment didn’t even mention that we were here. Is it not true that treaties are the supreme law of the land?

As a THPO who has participated in environmental reviews under the National Environment Policy Act (NEPA), I now question whether or not the law is adequate. Federal agencies want me to pin-point on a map the cumulative effect of the extractive industries without acknowledging that the cumulative effect is now global.

On February 8, 2016, I was appointed by my people to serve as THPO for my tribe. One of the first things brought to my attention was our resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. From the onset of my participation, I have struggled with trying to explain to a culture who has a different experience in this world than my people, what irreparable harms means to us. I’ve thought about it over and over again and can only explain it like this. While studying sociology at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado, a professor asked, “If you want to know what it’s like to be white in this country, who do you ask?” A young white student spoke up and said, “You ask a white person.” The professor, Jim Fitzgerald, Ph.D. said, “No, you ask an African-American or an Asian-American or a Native American because they live outside of that experience.”

I served in the U.S. military and come from a family with a long history of that. My father was a Vietnam veteran. I wanted to share that with you because I believe I understand what sacrifice and duty means. I believe that I understand what discipline means because at one time in my life I had to do things I didn’t want to do. Maybe writing this is one of those times. Because for me to come from where I came from, a place where I am surrounded by love and I live in peace, I had to step outside that comfort zone to write this declaration. Reaching out to a culture that isn’t aware of my experience in my own country.

When I joined the U.S. Army, I was asked if I spoke a foreign language. I replied, “Yes. English.” That is why I opened this declaration in my own language to help you to understand that I am descendant of an ancient people who has cultural affiliation to the land, the water, and the air going back to the beginning of time. I am much older than the concept of an American or a Native American. Ma Lakota, I am Lakota.

I don’t want you to feel sorry for me because I don’t feel sorry for myself. I come from a culture that had to deal with papal bulls which said a European religion could refer to me as a fractionated human being and force my ancestors through rape and torture to convert to their belief systems. I come from a culture that had to deal with doctrine of discovery which said a foreign people who came to this land had a god-given right to take it away from us. I went to school and learned about manifest destiny as if it was a good thing. I remember sitting in class embarrassed. When I got older, I learned about Carlisle, the first federally funded boarding school whose motto was, “To kill the Indian and save the man.” Despite everything that happened to us as a people, I don’t feel like a victim. Nahaci Lena Unkupelo, we’re still here. An ancient people deeply connected to our environment.

When in times of need, we reach out to and engage with a living universe. We call back to our ancestors for help and they come. Our chiefs still guide us today. Tatanka Iyotanke, a.k.a. Sitting Bull, once said “What promises have they made that they kept? Not one. And what promises have we made that we broke? Not one.”

I understand that the pipeline permits have been declared illegal and the court has ruled that the Corps should have complied with NEPA but did not. We have been saying this from the very beginning and being vindicated in our position was valuable. Despite this, the pipeline continues to operate. We won our lawsuit finding that the pipeline was permitted illegally, but the pipeline gets to operate anyway.

This is part of a pattern, a pattern where the rules are changed to benefit non-Indians at our expense. The U.S. government stole land promised to us in perpetuity, and the Supreme Court upheld that. Then the Corps built dams that flooded our best remaining lands, without our consent, and that was upheld, too. Now the rules have been changed again, so that a pipeline that never should have been authorized gets to keep operating, exposing us to risk and stress of catastrophe. This pattern has caused so much trauma and pain among the people in my Tribe. It signals to us that the government sees us as less. It signals that the government will never keep its word to us or meet its obligations to us. It signals that if we play by the rules of the U.S. legal system and win, the rules will be changed to our detriment. I have previously discussed the historic trauma that every Tribal member carries with them. Allowing this pipeline to continue operating will compound this trauma yet again, causing untold harm.

Established in 1987, Earthjustice's Northwest Regional Office has been at the forefront of many of the most significant legal decisions safeguarding the Pacific Northwest’s imperiled species, ancient forests, and waterways.