Oil Project in Arctic Put on Pause, But Other Fights Remain

The oil drilling project Peregrine is on pause, but another carbon bomb — the Willow Project — could get the go-ahead.

This page was published 3 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

A massive, climate-threatening oil project in the Western Arctic is on pause, in part because of legal pressure from Earthjustice.

If exploration leads to development, burning the oil drilled from the so-called Peregrine project would release a carbon bomb — exactly at a time when the world’s top scientists say we need to be transitioning to 100% clean energy or risk climate crisis.

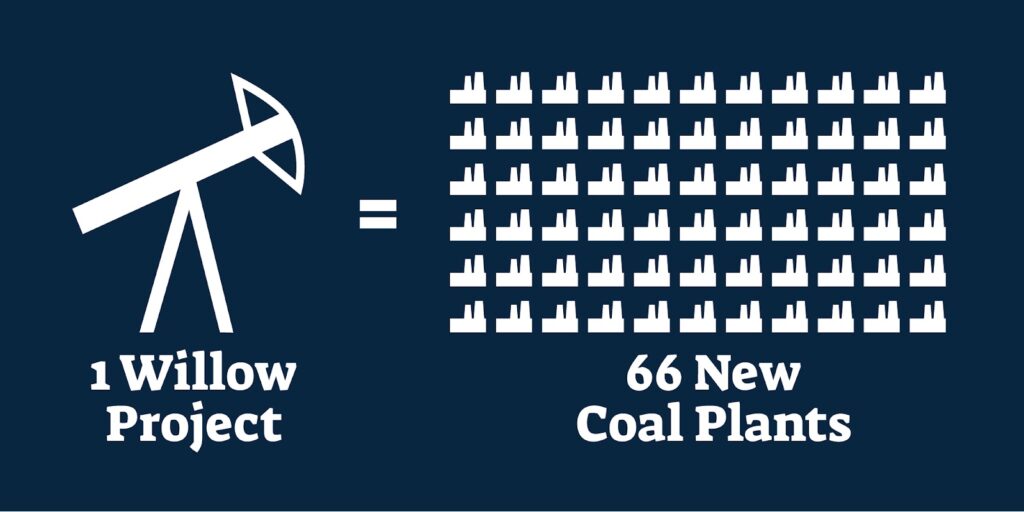

Though the Peregrine pause is a huge step forward in reducing oil and gas drilling on publicly owned, federal lands like those in the Arctic, a nearby fossil fuel project, known as Willow, could soon win approval to proceed. If approved, the Willow project’s carbon impact will be equal to powering one-third of all coal plants in the U.S. for a year. Earthjustice is fighting to end this project too — and keep all fossil fuels in the ground — because we cannot afford to further endanger our planet.

Fossil fuel pipelines crossing the Western Arctic in Alaska. (Kiliii Yuyan for Earthjustice)

The Peregrine project began in the winter of 2020/2021, after the company wagered that the public lands it had leased during the Trump administration could contain a massive amount of oil. 88 Energy sold the project to investors by claiming the area could contain up to 1.6 billion barrels of oil, which would have released staggering carbon emissions equivalent to firing up 173 coal plants for a year. This is in addition to the carbon emitted from the drilling project itself, which requires hundreds of thousands of gallons of fossil fuels each year to power construction, exploration, camp, and cleanup activities.

Despite Peregrine’s massive carbon output potential, the Biden administration’s Bureau of Land Management affirmed its approval without assessing the full climate impact. So in August 2022, we sued the agency, arguing that it violated a foundational environmental law called the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. Known as the “People’s Environmental Law,” NEPA helps communities protect themselves from dangerous, rushed, or poorly planned federal projects by requiring the government to thoroughly examine the proposed project’s consequences, including its climate impacts.

Meanwhile, Peregrine continued exploratory drilling, and they found less oil than expected, according to the Bloomberg report. That, coupled with “aggressive” litigation from Earthjustice and our clients, “has put a chill” on Peregrine, according to the Bloomberg report.

Caribou around the Lake Teshekpuk area in the Western Arctic. (Kiliii Yuyan for Earthjustice)

If the Peregrine project’s pause becomes permanent, the reversal will be a definitive win for the climate — and for one of the world’s last great, wild places. The Western Arctic, a 23-million-acre territory, is home to polar bears, musk oxen, and migrating caribou, and its wetlands serve as a nursery for migratory birds from every continent. Yet oil companies see the fact that this area remains “relatively unexplored” as a problem.

For years, the fossil fuel industry has crept further into sensitive areas in the Western Arctic, setting up drilling rigs, ice roads, airstrips, and mines. During the Trump administration, bids for new fossil-fuel drilling spiked dramatically, and now a patchwork of new leases have been doled out to oil giants. This includes the ConocoPhillips’ Willow project, which would permanently alter the Arctic tundra with five drill sites, a central processing facility, an operations center pad, 37 miles of gravel roads, ice roads, airstrips, 385 miles of pipelines, and a gravel mine.

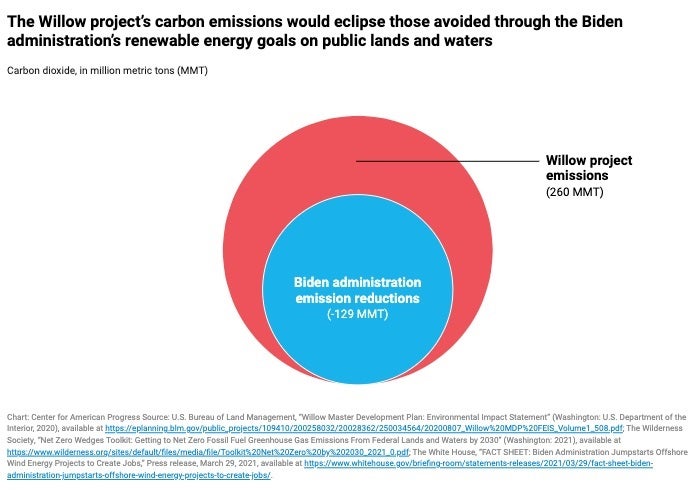

(Center for American Progress)

While the Biden administration has made significant strides toward addressing climate change, it may be poised to once again approve the Willow project after an Earthjustice victory in court last year sent the project back to the administration for reconsideration. The final approval of Willow could come soon, and ConocoPhillips has stated publicly that it intends to begin operations this winter. If Willow is allowed to proceed, the gravel roads snaking out from the development will pave a path for the oil industry to carve farther into the Western Arctic’s untouched lands.

“Climate change poses an urgent, existential threat,” says Earthjustice attorney Jeremy Lieb. “Faced with this crisis, green-lighting a new fossil fuel project such as Willow is incompatible with Biden’s climate goals, as well as maintaining a habitable life on earth.”

(Center for American Progress)

Earthjustice has successfully fought back against Willow in the past, even securing a rare court-ordered pause in early 2021 that prevented construction from proceeding and a court victory later that year vacating the project original approval. And we will continue our fight against Willow, as well as other fossil fuel fights in the Western Arctic that threaten people, critical species, and the place we call home. So far, more than 200,000 individuals have submitted comments in opposition to the Willow project. Will you join them?

Opened in 1978, our Alaska regional office works to safeguard public lands, waters, and wildlife from destructive oil and gas drilling, mining, and logging, and to protect the region's marine and coastal ecosystems.