How 600 Years of Environmental Violence Is Still Harming Black Communities

The first transatlantic voyages were only the beginning.

This page was published 3 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

Thousands of children in Flint, Michigan, were exposed to drinking water with elevated levels of lead in recent years. Meanwhile, in Lowndes County, Alabama, residents live with raw sewage because basic sanitation is not affordable. The fifth district of Saint James Parish in Louisiana is known as “Cancer Alley.” The concentration of industrial petrochemical plants causes high rates of cancer among local residents there.

All of these cases are in predominantly Black areas. Studies show that Black people are 75% more likely to live near oil and gas refineries, and Black Americans face higher risks of premature death from power plant pollution.

Teenagers play basketball in the Carver Terrace housing project in 2013 in Port Arthur, Tex.

(Eric Kayne for Earthjustice)

Although these are examples of the modern injustices affecting Black communities, they are born from environmental exclusion and violence that began hundreds of years ago. Below are examples of this history that, together, reveal a harmful pattern that Environmental Justice movements contend with to this day.

Creating a White Planet

After more than 600 years, the ripple effects of the Age Of Exploration continue to reverberate throughout society. The journeys and actions of Christopher Columbus and other European colonialists led to some of the most significant geographical and social transformations of the Modern Era.

In a matter of 100 years, nearly 60 million Indigenous Amerindians died due to foreign diseases, displacement, and wars waged on them by European colonial settlers. During this period more than 12 million Africans were forcibly transported to work as slaves in the United States and across the Americas.

These events changed the physical landscape of the Americas, altered global trade, and scaled the mass extraction of natural resources from the earth.

Enslaved workers plant sweet potatoes on a plantation in South Carolina on April 8, 1862. (Henry P. Moore / Library of Congress)

Without help from Indigenous populations, European settlers would not have been able to adapt to the American topography. Likewise, tropical African agricultural knowledge and skills were crucial to European settlers being able to successfully build plantation economies. European settlers appropriated skills and information from Indigenous Americans and enslaved Africans, but largely omitted these contributions from historical records.

For centuries, Black people have been prevented from defining our relationships to this land. Through government policies, economic institutions, and individual behaviors, Black people have been denied a safe and healthy environment.

The Homestead Act

In 1862 the Homestead Act gave European settlers up to 160 acres of unceded Indigenous land provided they live on it, claim it, and improve it. At the time, most Black people were still legally enslaved, and 90% of Indigenous people were wiped out — neither were seen as citizens. As a result, only European settlers could take advantage of this legislation that then built wealth for their families for future generations.

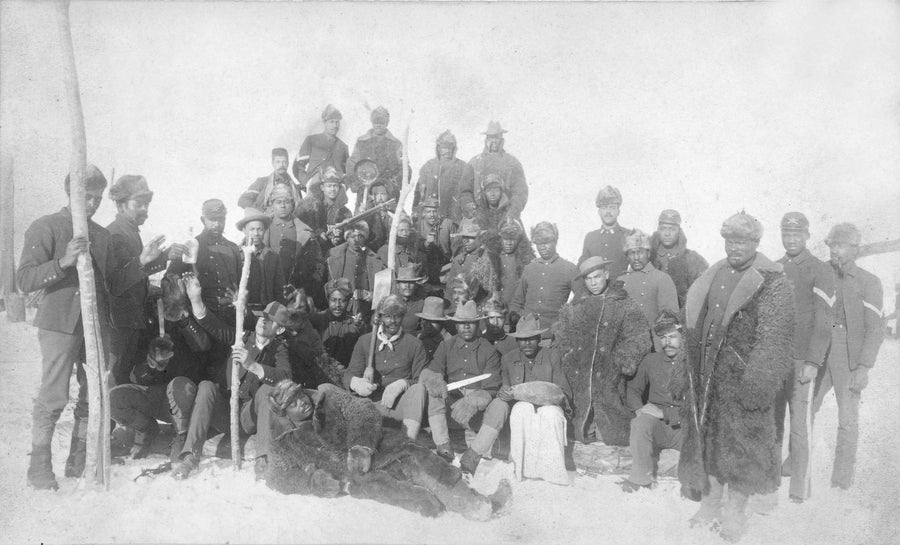

The Buffalo Soldiers

Buffalo soldiers of the 25th Infantry photographed at Fort Keogh, Mont. On Dec. 14, 1890. (Chr. Barthelmess / Library of Congress)

As early as 1866, after the establishment of Yosemite Valley as protected wilderness, a few national parks were being overseen by Buffalo Soldiers — the entirely Black cavalry and infantry regiments of the U.S. army who were, among other duties, stationed at national parks across the Midwest and West. They were among the first Park Rangers.

Despite this, national parks were not safe for African Americans, as lynching was widespread, and most national parks denied Blacks entry, anyway. Prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, people of color were legally excluded from (or segregated at) public recreational sites, including national and state parks, beaches, gardens, and lakes.

Continued Racial Exclusion

Farm workers from Florida, photographed near Shawboro, N.C., on their way to pick potatoes in Cranberry, N.J., in 1940. (Jack Delano / U.S. Farm Security Administration via Library of Congress)

Even after slavery was made illegal, Black people were still disenfranchised from land ownership and enjoying the great outdoors. This denial of opportunity came in many forms: racial terror perpetrated by the Klu Klux Klan, having their land poisoned and burned, exclusionary government policies, being denied aid after natural disasters, and not receiving loans for their farms.

These various experiences made it difficult for Black people to own, keep, and cultivate land. As a result, between 1916 to 1970, 6 million Black people migrated from the rural South to urban centers in the Midwest, West, and Northeast for more economic opportunities created by the World Wars. Even when Black families started moving into urban centers, they still experienced environmental racism.

Environmentalism will only succeed by acknowledging that injustices against Black and Indigenous people happen alongside the destruction of the earth.

Exclusionary urban planning and predatory banking practices emerged as Black migration changed the demographics of U.S. cities. Black people were forced to live in the most undesirable areas, in neighborhoods that cities divested from — near industrial sites. The conditions Black people were living in, as well as exclusion from outdoor recreation spaces, led to the coalescence of the Environmental Justice Movement.

This movement brought us some key environmental laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act. Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act led the way by prohibiting racial discrimination in any activities that receive federal funds, which includes national parks. The growing mainstream Environmental Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s looked very different from this, even though it was influenced by some of the organizing and tactics used by its predecessor.

A Movement for the Privileged

Left: Members of the Sierra Club hold “Save Grand Canyon” signs on the Canyon’s edge in 1966. Right: Havasupai tribal members and other conservationists rally to stop mining in the Grand Canyon in front of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco, Calif., in 2016. (Arthur Schatz / The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images; Chris Jordan-Bloch / Earthjustice)

The Environmental Movement was once mostly composed of and defined by middle-class White Americans advocating for the protection of wilderness, animals, and other things that were a luxury to enjoy.

This type of environmentalism ignored the degradation of environments and absence of green spaces in places inhabited by Black and Indigenous populations. It did not acknowledge how colonialism and racism justify putting profit over people, natural places, and ecosystems. Despite political gains such as the Wilderness Act and Endangered Species Act, it was a movement based on privilege.

A Planet for Us All

Participants in the First National People of Color Leadership Summit hold a rally at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., in 1991. (Courtesy of Robert Bullard)

In October 1991, the First National People of Color Leadership Summit took place in Washington, D.C. This summit recognized and brought to the forefront Black, Brown and Indigenous people’s leadership in protecting our environments and natural places. At this summit, 17 principles of Environmental Justice were drafted and adopted.

These principles remain relevant today, as the impacts from histories of exclusion and environmental violence continue to influence communities of color. A 2018 report indicated that Black Americans make up less than 2% of national park visitors, which suggests that our nation’s racial legacies are still potent in the natural places meant for us all.

Environmentalism will only succeed by acknowledging that injustices against Black and Indigenous people happen alongside the destruction of the earth. As the Environmental Justice and Environmental Movements grow to meet each other, we have to reckon with the past so that we do not reproduce it in the future.

Supporting organizations fighting for environmental, racial, and political justice helps create a sustainable planet for us all.

Originally published on March 30, 2021.