As EPA Drags Feet on Toxic Pesticide Ban, Parents and Teachers Take Action

As we take the EPA to court to force it to ban chlorpyrifos, communities are organizing to protect their kids.

This page was published 6 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

That night, the crop dusting plane flew so close that for a moment Bonnie Wirtz thought it was about to crash into her home.

Instead, it hovered above her rural Minnesota home, spraying pesticides onto the alfalfa field next door. The toxic white powder soon drifted into her air-conditioning unit. Then it seeped into the room where she was folding clothes, and then into her lungs with every breath she took. She started coughing.

“I was not able to breathe,” she says. Wirtz quickly looked for her then husband, and they both grabbed her infant son, who was in another room. They put a cloth over his mouth as they fled their house. He was not even a year old.

“I went into the emergency room and was almost in cardiac arrest,” Wirtz says. The rest of the family seemed fine, but doctors told her that the toxic agent was shutting down her central nervous system. They did not know if she was going to make it through the night, or what would happen once the medicine they gave her wore off.

After Wirtz survived the 2010 close call, she learned that the drift that nearly took her life was chlorpyrifos, a neurotoxic pesticide widely used in agriculture. Generally sprayed on crops such as corn, broccoli, apples, and citrus, chlorpyrifos is an organophosphate pesticide used to kill myriad pests.

This pesticide — pronounced klawr-pir-uh-fos — can also be poisonous to humans. It causes convulsions, respiratory paralysis, and even death by suppressing the enzyme that regulates nerve impulses in the body. Earthjustice, along with multiple partners, has for years pressed the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ban chlorpyrifos.

This summer, we won a huge victory: a court of appeals said the EPA must ban chlorpyrifos within 60 days, based on strong scientific evidence that shows this pesticide is unsafe. But Trump’s EPA filed for a rehearing at the last minute, leaving families in harm’s way and violating the law.

Our strategy now is to defeat this last-ditch challenge to the national ban. We will argue our case once more before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals the week of March 25. Meanwhile, we are supporting the work of community activists who are pushing for local bans as they educate their communities about how toxic all organophosphates are to farmworkers, families, and particularly children.

“I am hopeful that after winning the fight against chlorpyrifos, we’ll have sustained momentum to take on other harmful pesticides in federal and local venues, and get those off our food as well,” says Earthjustice attorney Patti Goldman.

The dire human health consequences of chlorpyrifos and other organophosphate chemicals are no accident. The Nazis weaponized organophosphates for warfare. After World War II, companies like Dow Chemical, the largest producer of chlorpyrifos, repurposed this nerve agent for home and agricultural use.

Decades of scientific research shows that chlorpyrifos can damage the developing brains of children, causing reduced IQ, loss of working memory, and attention deficit disorders. And indeed, this is what Wirtz says happened to her son, who was recently diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disorder. Her son was exposed as a baby, she says, because the family lived right next to fields for two spray seasons.

“So we were all exposed, as many families in rural areas are,” she says. “[Families] are exposed through the air they breathe and the water they drink.”

The evidence of danger is so clear that the pesticide was banned from residential use in 2000 because the EPA found unacceptable risks to children. Yet that first step left the much more lucrative agricultural use intact. So a pesticide that was too dangerous to spray on carpets remains commonly used on the fruits and vegetables the country eats. Over half of all apples and broccoli in the U.S. are sprayed with chlorpyrifos.

Despite the evidence of harm, from day one the Trump administration sided with Dow Chemical. In early 2017, it reversed the EPA’s own proposal to ban chlorpyrifos use from all food crops, alleging the science is unresolved. Earthjustice countered with a lawsuit. In August, the Ninth Circuit ruled in our favor, telling the EPA to implement the ban.

“What was so pernicious was the lack of any legal defense,” says Goldman, who argued the case before the Ninth Circuit. “In court, the lawyers refused to defend EPA on the merits. They just tried to keep the court from ever deciding. When the judges pressed, EPA lawyers’ responses reminded me of Richard Gere in the movie ‘Chicago’, when he did the tap dance to evade the truth.”

Under the helm of acting administrator Andrew Wheeler, Trump’s EPA has stalled on protecting the health of millions of families and farmworkers by asking for a rehearing.

“The EPA seems to be doing all that it can to make sure industry can extract every last cent from selling this poison,” says Earthjustice attorney Marisa Ordonia. “I am often asked how the EPA can keep delaying when they know about the risks to children. Usually this is both a legal and a moral question. I have an answer to the first part, but am at a loss as to the second.”

While the Trump administration procrastinates, another generation of families and their children eat, drink, and breathe a brain-damaging chemical. The brunt of that impact falls on rural communities, and especially people of color, since the majority of the farm labor workforce is Hispanic.

The good news is that in many of these communities, local activists are working to educate residents about the risks of chlorpyrifos and help them advocate for safeguards.

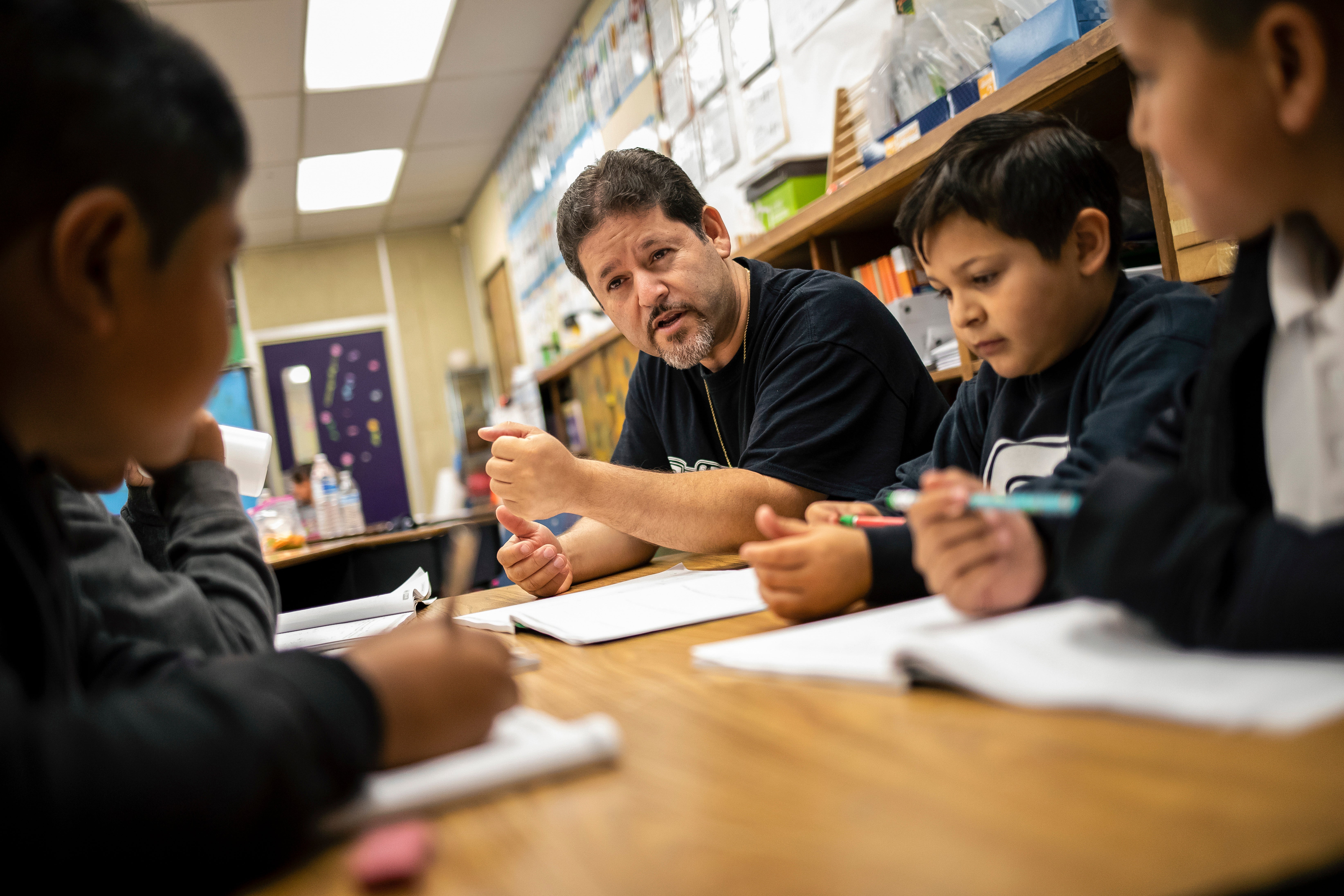

Salinas, a California farm town that’s known as the salad bowl of the world, is one place where community members are fighting for change at the local level. Oscar Ramos, an elementary-school teacher who has taught in the same Salinas school for 23 years, says he was moved to action when he realized that an increasing number of his students were being diagnosed with learning disabilities or being enrolled in special education.

Baffled by his observations, Ramos started reading up on studies connecting pesticides and learning disabilities. It turned out that University of California, Berkeley, researchers had studied families in Salinas for years to understand how organophosphates like chlorpyrifos affect the developing brain, and why pregnant mothers are particularly at risk when exposed. Just this fall, a peer-reviewed journal found that exposure to organophosphate pesticides like chlorpyrifos, even at low levels previously considered safe, can lead to cognitive problems in children.

“We have these adults who have read these reports that prove the connections from pesticide use and health … and they choose to ignore it,” says Ramos. “Politicians are putting profit over the health of our children. That is the most frustrating part for me.”

Ramos, who grew up in farm labor camps with crop-dusting planes serving as alarm clocks, has since become an activist with Safe Ag Safe Schools. The group is part of a statewide coalition pushing California to follow in the footsteps of Hawai‘i, where Gov. David Ige signed a bill in June to ban the pesticide.

In the meantime, the 44-year-old teacher has set out to protect his students from pesticides by teaching parents about the threat. Every year, he holds three weekend events where volunteers provide extracurricular activities to kids, while Ramos educates parents about pesticides and takes questions. Most of the students’ parents work in the fields.

“They don’t get that at work, they don’t get that education,” says Ramos, who notes workers often don’t know the impacts of pesticides, how the chemicals can cling to their clothes and end up in their home, or how toxic drift can reach their homes and schools. “We are trying to change that culture [of] parents not knowing and companies not educating, so we are taking on that role.”

But there are some questions Ramos can’t answer, particularly those that farmworkers who’ve been poisoned at work have about the law. To address that need, Ramos invites California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation attorneys, an organization that Earthjustice is representing in the chlorpyrifos ban case.

For attorneys working the federal case, these local efforts are much welcomed. “It’s been really inspiring to see the diverse groups of people and individuals that this fight has galvanized,” says Ordonia.

Among those leading the grassroots fight are mothers. In the town of Greenfield near Salinas, Yanely Martinez got involved when her preteen son, Victor, suffered an asthma attack for the first time. Moments earlier, pesticide fumes had drifted into his classroom from a vineyard. Victor was rushed to the emergency room.

Seven of the nearly one dozen pesticides used in the vineyard the day of her son’s incident were asthma-inducing, Martinez later learned. She is also convinced Victor has been exposed to chlorpyrifos drift while at school.

Martinez is using her power and platform as a city councilwoman to put pressure on state and federal officials to ban chlorpyrifos.

“We are not going away. We are going to continue doing our press conferences, our rallies, sending our op-eds to the newspapers,” says Martinez. “We are going to continue to be in their face.”

The pressure is starting to show results. California moved in fall 2018 to define chlorpyrifos as “an air pollutant that may cause or contribute to increases in serious illness or death.” A bill that would ban the pesticide completely has passed the Maryland House and is moving to a vote in the Senate, and similar bills have been introduced in New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Oregon.

Meanwhile, in Minnesota, Wirtz became a declarant on the federal lawsuit challenging the EPA’s delays and is following the latest developments. The appeals court could decide whether to rehear the case at any moment. It could deny the rehearing, but if the court grants the EPA’s petition, the rehearing could take as long as a year.

“Someone needs to step in … people are concerned about how long it’s taking,” says Wirtz. Nearly a decade after the accident, she now lives in the city so that her son can have the educational support he needs. She worries for the agricultural communities she left behind.

“It’s taking far too long,” says Earthjustice’s Goldman. “But we live in a country where judges can hold the government accountable to the law even if it takes time.”

The California Regional Office fights for the rights of all to a healthy environment regardless of where in the state they live; we fight to protect the magnificent natural spaces and wildlife found in California; and we fight to transition California to a zero-emissions future where cars, trucks, buildings, and power plants run on clean energy, not fossil fuels.

Established in 1987, Earthjustice's Northwest Regional Office has been at the forefront of many of the most significant legal decisions safeguarding the Pacific Northwest’s imperiled species, ancient forests, and waterways.

Earthjustice’s Sustainable Food and Farming program aims to make our nation’s food system safer and more climate friendly.