What It’s Like to Be Boxed In By Amazon

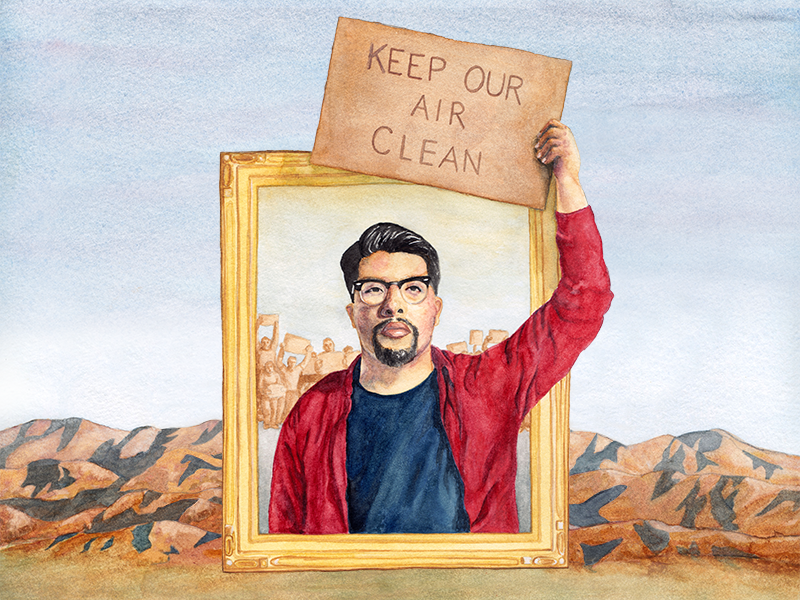

As online shopping booms, warehouse workers and communities near internet retail logistics centers are demanding solutions to protect their health and environment.

This page was published 4 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

Online shopping, shifted into overdrive by the COVID-19 pandemic, is here to stay. But the logistics operations behind internet retail companies like Amazon are often as problematic as they are profitable, with a long history of skirting environmental laws and exploiting workers.

In the Inland Empire, a giant logistics hub located an hour east of L.A., residents outside the warehouses regularly choke on the thick, black smoke of diesel emissions wafting from the industry’s army of idling trucks. They’re kept awake by the constant low rumble of giant semis barreling along the interstate, and the high-pitched whir of cargo planes flying overhead.

Inside the warehouses, the morale stinks as bad as the air pollution.

J.J., an Amazon employee whose name has been changed to protect their identity, says that many of the people they started with a few months back are gone — having already quit or been fired.

“I worry about my job security,” says J.J., who’s been reprimanded for helping other workers while they take a bathroom break. “But I feel more comfortable than average because I try to work as much as two or three people… though I barely get paid as one.”

The COVID-19 crisis has made this situation even more unbearable, with long-term exposure to air pollution linked to worse health outcomes for people fighting COVID-19. But environmental health activists and labor organizers across the country are rising to the moment. In the Inland Empire, as lawmakers roll out the red carpet for yet another massive Amazon logistics center, environmental justice advocates, union members, faith leaders, and local families are demanding an upgrade from one of the pandemic’s most profitable companies.

And they’re making significant progress.

The Inland Empire wasn’t always the epicenter of the miles-long warehouses, big-rig semis, and heavy-duty machinery that supply our online shopping demands. “America’s Shopping Cart” was once a major hub for the citrus industry. Communities of color, pushed to the Inland Empire through historic patterns of redlining and discriminatory land use policies, made their homes below the towering San Bernardino Mountains.

In the 1970s, however, the valley of oranges transformed into a valley of warehouses after cheap land combined with easy access to numerous freeways, railyards, and shipping ports lured in the booming logistics industry. In the past decade, nearly 150 million square feet of warehouse space has been built in the Inland Empire, the equivalent of about four Central Parks. It’s no wonder then that toxic diesel fumes from the area’s countless semi trucks and trains now hang over the valley, trapped by the San Bernardino and San Gabriel mountains and joined by more pollution from nearby L.A.

The end result smells like a lit cigarette dropped into a bottle of orange Fanta.

“I feel drained, my chest feels tight, I have difficulty breathing, and everything takes more energy,” says Angelica Balderas, a 39-year-old Inland Empire resident who went to the hospital at least five times in 2019 seeking medical attention for respiratory issues.

Balderas is hardly alone. The Inland Empire has some of the worst ozone and soot pollution in the country. San Bernardino and Riverside counties, which encompass the region, have asthma rates twice as high as the national average.

Anthony Victoria-Midence, a longtime local environmental voice, says that building more warehouses in the “diesel death zones” will sicken even more people in an area that’s already overburdened by pollution. And though more warehouses will inevitably mean more jobs, the question is at what cost. News reports have described the warehouse environment as “soul crushing,” where employees are treated like “robots” and injuries are common. Fewer than half the jobs in the Inland Empire pay a living wage.

“It’s like this slow violence that the e-commerce chain inflicts,” says Victoria-Midence, “It’s a cycle of madness.”

Inland Empire residents were livid when they first learned of a proposal to build a massive new warehouse in their neighborhood. The 700,000-square-foot facility, which began operations this spring, is estimated to emit a literal ton of air pollution each day into the community. The project will also bring with it round-the-clock flights (about 24 per day) and 500 daily truck trips to the suburban area.

In December 2019, late in the evening on Cyber Monday, about 100 people gathered in front of one of Amazon’s many warehouses in the Inland Empire. They were armed with a list of demands for Jeff Bezos, the former CEO of Amazon and one of the world’s richest people. (Bezos makes about $2,489 per second, more than twice what the median U.S. worker makes in a week.)

Area residents and union members are asking Amazon to provide the community with basic quality-of-life benefits like guaranteed living-wage jobs and strong pollution reduction plans at the proposed facility. Specifically, they’re pushing Amazon to purchase zero-emissions electric trucks, which will keep the air free of harmful diesel pollution.

While companies like Amazon might tout commitments to electric delivery fleets in their customers’ neighborhoods, in order to protect the people trying to breathe in diesel death zones they need to electrify their diesel trucks and equipment.

“That means none of this ‘near’ zero emissions crap,” says J.J. “That’s pretty much jargon to pass off something like natural gas, which is definitely still a source of pollution.”

J.J. came to the environmental justice movement a few years back, after seeing a YouTube video explaining the urgency of the climate crisis. J.J. decided to get involved with groups like the Sunrise Movement, which calls for expansive, visionary policies like a Green New Deal to address climate change.

While at work, J.J. is careful to keep quiet about their extracurricular activities. During the Cyber Monday protest, J.J. covered their face and took off their glasses to mask their identity. Even before the pandemic, J.J. says, people at work have sometimes worn literal masks, designed specifically to filter out air pollution.

Pastor Kelvin Ward, a former Amazon employee who grew up in Riverside, can also attest to the warehouses’ hazardous working conditions. During his almost three years working there, Ward saw employees so strapped for time that they would choose not to walk to the bathroom. Maintenance workers often claimed they would find human waste in the trash receptacles.

“What I saw when I was there, it was inhumane,” says Ward. “We were treated like slaves.”

During the Cyber Monday action, protestors blocked one of Amazon’s driveways so that the company couldn’t fulfil its orders on the busiest shopping day of the year. Ward, who spoke at the protest, took satisfaction in pushing back against a company that doesn’t invest in the wellbeing of the surrounding community.

Says Ward, “We did our part.”

A coalition of groups against the new warehouse has also organized several actions to say “enough” to the endless tide of warehouse expansions in the Inland Empire. Outside the region, they are supported by groups demanding that Amazon take stronger climate action and enact better COVID-19 protections for workers, 20,000 of which have tested positive for coronavirus.

While local and national pressure mounts for a cleaner logistics industry, Earthjustice is applying pressure inside the courtroom. On behalf of coalition members like the Sierra Club and the Teamsters Local 1932, Earthjustice has sued the Federal Aviation Administration for its failure to adequately assess the proposed warehouse’s environmental impact to residents of San Bernardino. In February, the court heard oral arguments in the case.

“The federal government’s insistence that this project will have no significant impact is wild. It means a lot of additional air pollution in one of the most polluted counties in the country,” says Earthjustice attorney Adrian Martinez. “So if this project doesn’t have an impact on our air pollution, then nothing will.”

Martinez adds that the cursory review by the federal government, working with the San Bernardino International Airport Authority, is “just a slap in the face to everyone who lives here and who cares about these important issues.”

The warehouse lawsuit is part of a broader fight to clean up Southern California’s notoriously dirty air. Known as the Right to Zero campaign, it aims to electrify everything that moves — from heavy-duty trucks to public transit buses, cars, and port equipment — and run it on a clean energy grid in order to save lives, protect our climate, and strengthen the economy. For years, the goods movement industry has largely flown under the radar despite the industry’s significant climate impact from its diesel-powered ships, trains, trucks, and construction equipment.

But the tide is shifting. After seven years of community activism and advocacy, regulators in Southern California passed a landmark rule in May that will slash air pollution from mega-warehouses by 10 to 15%. The new rule, which applies to mega-warehouses such as Amazon’s terminal in the Inland Empire, will require warehouse operators to electrify the trucks traveling to and from warehouses or take other measures to improve air quality, creating local jobs while cleaning up the environment. It’s a key early step to reining in pollution from the historically underregulated industry.

And in April, our lawsuit against the World Logistics Center, the world’s largest master-planned warehouse development, resulted in a landmark settlement that will invest up to $47 million in electric vehicles, rooftop solar, and other solutions in the Inland Empire, where the 40 million square foot facility will be located.

J.J. says that if companies like Amazon are as passionate about climate change and community welfare as they claim, they should continue to agree to the demands that local residents and workers are saying will benefit the community.

“If you really want to be a leader for change, this is how you do it,” says J.J. “Listen to the community, and deliver the solutions they’re asking for.”

This piece was originally published in April 2020 and has been updated to reflect the latest news.

The California Regional Office fights for the rights of all to a healthy environment regardless of where in the state they live; we fight to protect the magnificent natural spaces and wildlife found in California; and we fight to transition California to a zero-emissions future where cars, trucks, buildings, and power plants run on clean energy, not fossil fuels.