June 26, 2025

Mapping Soot and Smog Pollution in the United States

Under the Clean Air Act, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency must set standards that protect public health from common air pollutants, such as fine particulate matter (also known as soot) and ground-level ozone (also known as smog).

Though we know about many areas that have unsafe levels of air pollution, we don’t know the full extent of the problem.

Many urban and rural areas — about two-thirds of counties in the United States — lack air monitors. This means many communities have no way of knowing the state of the air they breathe.

Rigorous monitoring is critical for protecting public health.

Smog Air Pollution

By county in 2024

What is smog? Ground-level ozone (also known as smog) is a result of emissions from industrial sources such as power plants, refineries, and factories, as well as from motor vehicles, combining with sunlight in the atmosphere.

Health impacts of smog Can trigger asthma attacks and increase the risk of heart and lung diseases — particularly in children, older adults, and people who are active outside, such as outdoor workers

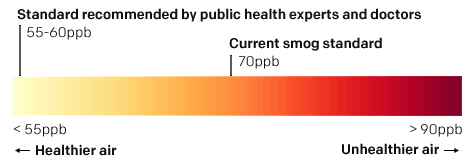

The Smog Standard: Measures average smog levels over 8-hour periods. Currently set at 70 parts per billion.

When the national standard for smog was finally updated in 2015 — following a court-ordered deadline secured by Earthjustice in a lawsuit on behalf of health and environmental groups — EPA's independent science advisors warned that it might not be adequately protective.

After years of research, there is more clear evidence that a stronger, science-based smog standard is necessary.

In 2023, the EPA restarted the rulemaking process for strengthening protections against smog. This process could take several years.

Soot Air Pollution

By county in 2024

What is soot? Fine particulate matter (also known as soot or PM2.5) originates from sources such as fuel combustion and industrial processes.

Soot consists of tiny particles that can penetrate the lungs and bloodstream.

Health impacts of soot Causes death and serious health harms, such as heart attacks and strokes — especially in older adults — and associated with conditions such as asthma, Parkinson's disease, dementia, low birth weight, preterm birth, and infant mortality

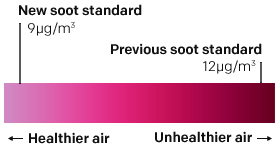

The Soot Standard: Measures average soot levels over one year. In 2024, EPA updated the standard to a more protective 9 micrograms per cubic meter from 12 µg/m3.

For more than a decade, Earthjustice has filed legal actions on behalf of our clients to compel the EPA to follow the Clean Air Act’s requirements to protect the public’s health and well-being from the harms of soot pollution.

In 2024, the EPA strengthened the annual particulate matter standard from 12 micrograms per cubic meter to a more protective standard of 9 µg/m3. This will reduce air pollution across the country and ensure that states respond to the ongoing public health and environmental justice crisis, saving thousands of lives and avoiding 800,000 asthma symptom cases every year.

How air monitoring works — and saves lives

Under the Clean Air Act, the healthy air standards set by the EPA — known as “national ambient air quality standards” or NAAQS — must protect public health with an adequate margin of safety.

A network of official air quality monitors sample the air in various counties to determine whether air quality meets or violates the standards. Areas with unhealthy air must take steps to clean up their air.

Here’s how air quality standards can make a difference to your air:

- When an industrial polluter wants to open a new facility, it must apply for air permits. Those permits will only be given if the operator can show that the added pollution won’t tip the region’s air quality over the legal limits.

- And if a region’s air quality is worse than the standard, state governments must draw up and execute plans to curb air pollution so that air quality will meet the standard.

For soot, such a plan could involve cutting car traffic by improving public transit or instituting carpool lanes. Or, if there are industrial facilities such as coal-fired power plants that do not have modern scrubbing technology, the state can compel them to clean up their emissions.

Study after study shows that while everyone is harmed by air pollution, the areas with the dirtiest air continue to be disproportionately lower-income communities and Black or Latino neighborhoods.

An EPA air monitoring station near Grand Isle in Jefferson Parish, LA. Eric Vance / U.S. EPA

The Clean Air Act: A Success Story, with Many Chapters Still to Come

Since it became law fifty years ago, the Clean Air Act has been a remarkable success, substantially improving the lives of millions.

But there is more that needs to be done to fulfill the Clean Air Act's promise — far too many are still breathing dirty air and suffering as a result, despite the benefits that clean air provides to our economy and our society.

Earthjustice works to protect our right to breathe by securing the strongest possible health protections and preventing the most dangerous polluters from dodging their legal requirements to clean up our air.

A year after it asked for input, the EPA made a significant step in 2024 in our ongoing efforts to fulfill the promise of the Clean Air Act by finalizing a more protective standard for soot pollution. Your voice makes a difference.

Willie Dodson of Appalachian Voices, installs an air monitor onto a house in Wilson Creek, Kent. Data collected from the devices can help local residents understand the risks they face and empower them to advocate for stronger air quality standards. About this photo. Michael Swensen for Earthjustice

About the map data

Based on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s “design values” for annual particulate matter pollution (PM2.5) and 8-hour ozone for U.S counties.

A “design value” is the official EPA measure of whether a county complies with the primary (health-protective) annual national ambient air quality standard. Design values are derived from air quality monitoring data that comes from air quality monitors operated by governmental agencies, like EPA or states, that sample the air to measure the amount of pollutant in the air.

Not all counties in the United States have an official air quality monitor.

The design values shown here are computed using Federal Reference Method or equivalent data reported by state, Tribal, and local monitoring agencies to EPA's Air Quality System (AQS) as of May 28, 2025.

Concentrations flagged by state, Tribal, or local monitoring agencies as having been affected by an exceptional event (e.g., wildfire, volcanic eruption) and concurred by the associated EPA Regional Office are not included in these calculations.

Top photo credits:

- Smog clogs the air around the 405 freeway in Los Angeles, Calif. (Andi Patz / Getty Images)

- Visitors to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park look through the haze as they stand at an overlook at Look Rock near Townsend, Tenn., in 2006. The most frequently visited park in the nation and within a day's drive for two-thirds of all Americans, the park has air quality similar to that of Los Angeles. (Chuck Burton / AP)

- Marti Blake lived next to the Cheswick Generating Station. In 2010, Blake showed the amount of soot and pollution that accumulated on the side of her house in less than a week. (Chris Jordan-Bloch / Earthjustice)

- Smog hangs over the hills where cattle graze in the San Joaquin Valley, Calif. (Richard Thornton / Shutterstock)

Earthjustice’s Washington, D.C., office works at the federal level to prevent air and water pollution, combat climate change, and protect natural areas. We also work with communities in the Mid-Atlantic region and elsewhere to address severe local environmental health problems, including exposures to dangerous air contaminants in toxic hot spots, sewage backups and overflows, chemical disasters, and contamination of drinking water. The D.C. office has been in operation since 1978.