Agriculture, Climate, and 2023 Farm Bill (A 3-Part Blog Series)

About the 3-blog series on helping American agriculture become more resilient and climate-friendly:

What we grow and consume in America has a profound impact on our lives. It is also directly influenced by federal policy, and most importantly the Farm Bill, a collection of government programs that requires renewal every five years. This sprawling legislation governs initiatives from farm subsidies to low-income nutrition support. In our first blog in this series, The Real Cost of Food, we explain the severe environmental and climate impacts of modern industrial agriculture. These harms are not widely known and yet prevent our country’s achieving our clean air and water, climate stability, and health and species protection goals.

In our second blog, Ripe for Change, we discuss the many sustainable practices that could improve our climate and environment, farmer livelihoods, and communities’ health. Thanks to the good work of many farmers and ranchers already, we know what can and should be done. Our challenge is to accelerate adoption of these practices.

In our third blog, Harvesting Climate Benefits from the 2023 Farm Bill, we dive into the Farm Bill itself. We detail four ways Congress can use the Farm Bill reauthorization to help farmers become more resilient in the face of climate change while lowering the sector’s significant environmental impact.

Article 1: The Real Cost of Food

U.S. agriculture appears to be a marvel. Our food system produces billions of pounds of food and fiber every year at a very low out-of-pocket cost to the consumer. Most Americans enjoy a wide variety of foods at their markets in all seasons (though much of the fruits and vegetables are imported). The American food system’s efficiency in churning out seemingly inexpensive calories is the envy of the world.

But when we consider the dramatic adverse impacts on the environment, our health, and food and farm workers, many studies have found the true cost of food is triple the price we see at the grocery store. While our industrial food system is producing food that appears inexpensive and abundant, it’s also one of the largest sources of water, air, and climate pollution in the country. Most consumers — and, sadly, most lawmakers — don’t consider these environmental impacts or the poor treatment of workers and animals when discussing U.S. agriculture policy.

Instead, most Americans may have a pastoral vision of small, integrated, family farms as the place where our food originates. Yet that is far from reality. Today, most cropland is a vast monoculture of just one or two industrial-scale, chemical-intensive commodity crops, while about 99% of farmed animals are raised in “concentrated animal feeding operations,” (CAFOs) that crowd tens of thousands, or even millions of animals into restrictive stalls or pens. And while, at one time, most Americans worked on farms, now less than 2% of Americans farm or ranch. Consolidation has gotten so extreme that only 6% of farming operations produce 90% of all of meat, dairy, and poultry.

Industrial agriculture’s massive footprint occupies over 60% of the contiguous U.S. This land used to be vast wetlands, native grass-covered prairie, or forest — natural systems adept at storing carbon, producing abundant wildlife, and filtering polluted water. And this conversion of land is continuing — between 2007 and 2012, 7.8 million acres of natural habitat were converted to cropland due to ethanol mandates and increased global demand for livestock feed. Today, very little agricultural land provides these important environmental benefits.

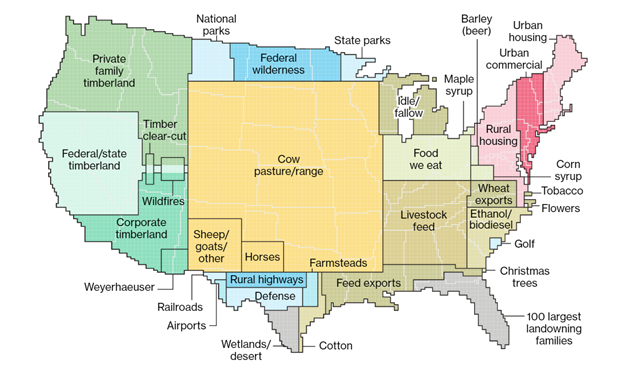

“Here’s How America Uses Its Land” (Courtesy of Bloomberg)

And though industrial agriculture occupies more than half the land in the U.S., only 20% of that land is used to grow food that humans directly eat. The remaining agricultural land is devoted to grazing or animal feed even though Americans only get about 30% of their calories from meat. Thus, as it turns out, our industrialized system of meat-focused food production is quite land-inefficient.

Not only is it inefficient, but industrial agriculture is also closely tied to the petrochemical industry because of its dependence on fossil fuel-based fertilizers and pesticides. The American Gas Association released a study in March touting the fossil fuel’s direct link to commodity agriculture, saying, “An abundant and affordable supply of natural gas is critical to the fertilizer industry and our ability to provide essential crop nutrients to farmers.” Excess pesticide and fertilizer use causes massive disruptions to natural ecosystems, including the massive “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico and the destruction of pollinator habitats critical to our food supply. At the same time, these toxic chemicals are harming rural communities which must contend with the expensive removal of nitrate pollution from drinking water, while increasing their risk of numerous human health harms, including blue baby syndrome. New research is also linking nitrate consumption to adult and pediatric cancers.

Of all the true impacts of industrial agriculture, perhaps the one that is least understood and yet most critical to address is on our climate. This impact is so great that the country and the world simply cannot meet our collective climate goals without significant changes to how we grow food. And while other sectors are reducing their emissions, agriculture’s emissions are rising, thereby increasing its proportional share of climate emissions. Most people are not aware of this climate-agriculture connection because agriculture’s climate pollution green house gases do not come from huge smokestacks but from biological sources — cows, corn, and, manure (or “crap” to be alliterative) and the land they are on — that are harder to see.

The two primary greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture are methane and nitrous oxide. Bovine guts generate methane, which is 85 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over 20 years. The millions of cows in the U.S. emit more methane than the fossil fuel gas system. Nitrous oxide is even more damaging to our atmosphere. It’s released in large volumes by animal manure and when farmers routinely apply more nitrogen fertilizer than animal feed crops require. Then, when wild and fallow land is plowed to feed this inefficient system, the land releases tremendous amounts of stored carbon. And land already converted to agriculture is a missed opportunity for carbon sequestration. Thus, collectively, our industrialized agriculture and food sector drives approximately one-third of our country’s contribution to climate change — about the same as the transportation system’s total climate emissions.

The good news is that this sector is ripe for change.

[Read Article 2: American Agriculture is Ripe For Change]

[Read Article 3: Harvesting Climate Benefits from the 2023 Farm Bill]

Earthjustice’s Sustainable Food and Farming program aims to make our nation’s food system safer and more climate friendly.

Nydia Gutiérrez

Public Affairs and Communications Strategist, Earthjustice

ngutierrez@earthjustice.org