Consumers Hold the Power for Change; We Do Have a Choice Outside of Unsustainable Industrial Agriculture

Further industrializing animal agriculture is a short-sighted and dangerous response to food security; broader thinking leads to far better answers.

Recent essays in the New York Times and Washington Post repeat the arguments in articles defending the current model of intensive industrial agriculture, arguing that it uses less land — and therefore has a smaller footprint — than environmentally friendly alternatives. These articles acknowledge the unavoidable fact that agriculture is “eating the planet.” It’s responsible for a quarter of or more of global greenhouse gas emissions and it is the leading cause of water pollution, deforestation, and biodiversity loss. As the pandemic showed, highly specialized industrialized systems are also less resilient. But these articles dismiss opportunities for meaningful reform, instead arguing that we must double down on unsustainable practices to feed our growing population.

These arguments rest on a flawed premise. They assume that we must continue producing the same (or more) quantity of the same food, especially beef, in the same way that we do now. It’s the equivalent of arguing that we should pursue clean energy — but dismissing solar and wind in favor of incrementally updated fossil fuel power plants. Or asserting that the future of transportation is slightly more efficient internal combustion engines, while discounting electric vehicles. If it were not for fossil fuel lobbyists, it would be obvious to all that such approaches make no sense.

The argument also assumes that future conditions will remain the same as they are now, despite the undeniable reality that the weather is changing. But livestock suffer in high heat, and concentrated monocultures are particularly susceptible to extreme weather, as the rise in crop insurance and disaster payments demonstrate.

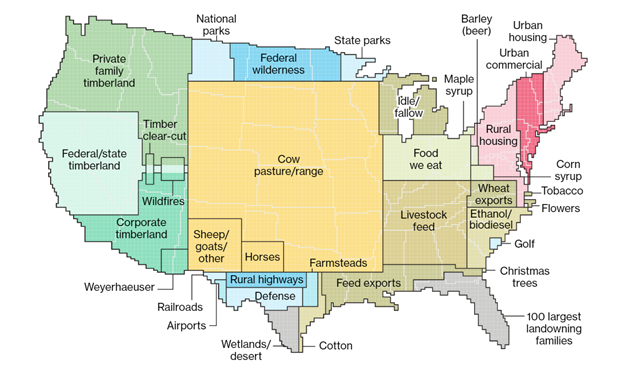

Instead of throwing up our hands in despair, we should strive to produce less waste and more real, nutritious food — not fuel or animal feed or artificially inexpensive, empty calories. Currently, nearly 60 million acres — that is, more than 15% of all U.S. cropland, the equivalent of Illinois and Indiana combined — are used to grow crops for ethanol and biodiesel, which studies show are worse for the climate than gasoline. (The same amount of land, devoted to solar production, would produce 300 times as much transportation energy.) Eduardo Porter in the Washington Post merely shrugs at this reality. Before they go to feedlots, cattle graze on hundreds of millions of acres of federal land, rented at below market rates, and over 100 million acres are devoted to animal feed, which is hugely inefficient — it takes over 10 pounds of grain to add a pound to beef cattle (of which only about 60% can be eaten). Millions more acres are devoted to commodity crops for sugar and corn syrup that make us sick. One-third of all food is wasted, most of it left to rot in landfills.

Bloomberg’s “Here’s How America Uses Its Land”

Industrial agriculture doesn’t feed the world. It feeds itself, perpetuating a cycle of overproduction, sickness, and environmental degradation — and taxpayers foot the bill with tens of billions of dollars of direct subsidies every year.

Michael Grunwald in the New York Times admits that industrial agriculture should pollute less, but his whole argument undercuts efforts to achieve that result. Mega-farms currently spew air and water pollution with virtual impunity, protected by exemptions in the laws, weak or nonexistent regulations, and a near total lack of transparency. And even though agricultural pollution imposes billions of dollars of costs on drinking water providers and other industries, Big Ag’s lobbyists, among the most powerful in Washington, ensure that meaningful oversight remains elusive.

And as long as Grunwald and others refuse to contemplate a cleaner future, the situation is unlikely to improve. Earthjustice and our allies seek to elevate the voices of others — those down wind or downstream of industrial animal factories or those who work on farms. These constituencies far outnumber farm land owners (who receive the subsidies) but lack their political clout. They do not blithely accept the status quo and should be in the conversation.

These writers are willing to excuse all the air and water pollution because, they assert, that intensifying agriculture alone will save forests. Would it be so simple. Of course, higher yields can reduce global demand for agricultural land, but higher yields also often make farmland more profitable, incentivizing nearby landowners to convert even more forests and grasslands into crops. Without strict protections for natural ecosystems, efficiency alone will not spare nature. Industrial agriculture’s track record makes this clear: its success doesn’t lead to conservation; it often fuels expansion. And if the market is already flooded with some commodity crop, lobbyists use their clout to create new markets for those now-more-profitable crops, such as “sustainable aviation fuel.”

Also troubling is the dismissal of demand-side solutions. Both recent essays dismiss the possibility that people might be willing to eat less meat—but they ignore the decades of subsidies and policies that make industrial meat artificially cheap, coupled with sophisticated, and often misleading, marketing campaigns. If the true costs of beef — likely over $30 per pound — were reflected in the price, demand would plummet. Those who believe in government fiscal responsibility have long objected to these subsidies, and those who are concerned about public health have raised the alarm about the fact that we waste the majority of our antibiotics to compensate for unsanitary conditions at animal factories, helping to breed “superbugs.” Maybe it’s time to listen to them.

This rejection of viable systemic alternatives reinforces a risky narrative: that the only path forward is the one we’re already on. Does anyone really think that 50 years from now we will be using precious fertile land to power vehicles or raise entire animals for portions of their flesh? Or burning rocks to generate electricity?

Industrial agriculture exploits the planet, produces often unhealthy food, and devastates rural communities, all while hiding behind a façade of efficiency. It increases risk and is vulnerable to climate change and other shocks. The future of food cannot be built on this broken foundation. Rather, as Earthjustice and our partners are advocating, we need broader understanding of the impacts, rather than excuses to put on blinders; we need to bring all stakeholders to policy making, not just the beneficiaries of the current system; we need to look throughout the food system, rather than limit ourselves to minor tweaks of the status quo. Change is possible, but only if we demand it.

Earthjustice’s Sustainable Food and Farming program aims to make our nation’s food system safer and more climate friendly.

Nydia Gutiérrez

Public Affairs and Communications Strategist, Earthjustice

ngutierrez@earthjustice.org