Island in the Sun

Organizers in Puerto Rico say moving to solar power could break colonial ties.

As Hurricane Maria advanced on Puerto Rico, the pressure from the 155 mph winds grew so intense that Laura Arroyo feared the windows of her apartment in the capital city of San Juan would shatter.

The environmental attorney, her teenage son, and her husband raced to open the windows to relieve the pressure.

When heavy debris started flying, the family hid in a closet for protection. Soon, their roof was compromised, and water began pouring through the ceiling. They used all the linens and towels they had to mop up and protect their furniture.

“It was so difficult,” says Arroyo, fighting back tears. For three weeks, she couldn’t reach her parents to see how they were faring.

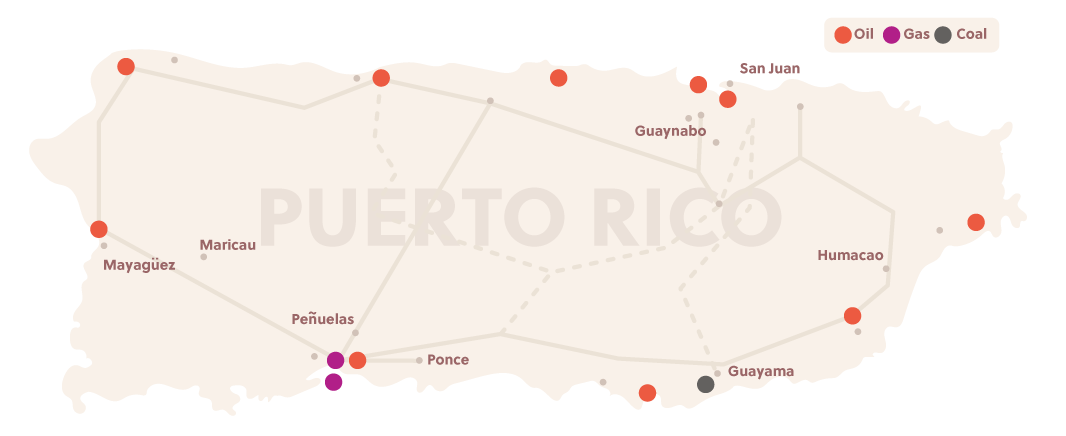

After the storm in September 2017, Puerto Rico was in shambles. Across the island lay broken power lines that once had run through forests and over mountains, moving electricity from the oil and gas plants concentrated in the south to the more populous areas in the north.

It took nearly a year to restore electricity to all of Puerto Rico’s three million residents. Most of the estimated 3,000 people who lost their lives due to Hurricane Maria died in the weeks following the storm, when oxygen devices failed due to the loss of power, or medicine requiring refrigeration became useless.

“A lot of environmental groups realized that energy had to become the main issue for them,” says Arroyo, who became an Earthjustice attorney shortly after the storm. “It was evident the electric system was a mess.”

Puerto Rican environmental advocates soon saw an opportunity to do more than just fix the mess. A grassroots environmental coalition, Alliance for Renewable Energy Now, proposed a plan to revolutionize the way the island harnesses and distributes energy. By building a network of rooftop solar panels, they realized, Puerto Rico could become more resilient to extreme weather, reduce pollution and climate emissions, and move toward independence from imported fossil fuels — all with much lower costs for energy users.

While those goals line up with priorities set by Puerto Rico’s government, the coalition faces stiff opposition from fossil fuel companies that want to keep the island reliant on oil and gas imports. Those companies have found sympathetic ears among a group of officials who have sweeping, undemocratic authority: the oversight board appointed by the U.S. government to control Puerto Rico’s finances.

Earthjustice is representing Alliance for Renewable Energy Now as it fights to clear a path toward a safer, cleaner, more self-determined future.

A large Caribbean island with many smaller satellite islands, Puerto Rico is known for its abundant sunshine, making it an ideal place to harvest solar power. In fact, Puerto Rico gets enough sunlight to meet its residential electricity needs four times over. Yet less than 3% of the island’s energy comes from renewable sources.

Fossil fuel interests and U.S.-appointed bureaucrats would like to keep it that way. Their intervention is part of a long history of the marginalization of the island’s people.

Starting in the 1500s, Spanish colonists grew rich by pushing Puerto Rico’s indigenous Taíno people off their ancestral lands and forcing enslaved Africans to work the soil. In 1898, the U.S. went to war with Spain and seized the island, but maintained extractive authority and unfair power structures. Today, Puerto Ricans, although U.S. citizens, can’t vote for the U.S. president and have no voting members in the House or the Senate.

This pattern of colonial exploitation has kept Puerto Rico tethered to offshore fossil fuel companies. Today, rusting power plants burn imported oil and gas, polluting the air with mercury and sulfur dioxide. Rotting poles support sagging wires that transmit electricity across the island. For this dirty energy, Puerto Ricans pay higher and more volatile rates than mainland U.S. residents — sometime as much as 2.5 times higher.

At that price, the power grid should work reliably. But Amy Orta-Rivera, an environmental policy coordinator who works with the social justice organization El Puente-Enlace Latino de Acción Climática (El Puente-ELAC), says the system regularly fails even in nice weather.

“Me and my family lose power an hour or two, like three times a week,” says Orta-Rivera. “That is not a good system.”

El Puente-ELAC is part of the Alliance for Renewable Energy Now coalition that is pushing Puerto Rico toward energy independence.

The coalition’s plan is called Queremos Sol — Spanish for “We Want Sun.” It shows how Puerto Rico could meet all its energy needs with small solar grids distributed throughout the island. This localized system would be better equipped to withstand and recover from storms like Hurricane Maria, which will become more frequent as climate change intensifies.

“If something happens with your own rooftop renewable energy, it could be fixed more quickly than an entire system repair, which is the way it’s designed right now,” says Orta-Rivera.

Distributed solar would not require transmitter towers exposed to winds at high altitudes. And energy storage in batteries could more easily support the island’s electricity needs during disruptions.

Ruth Santiago, an environmental attorney under contract with El Puente-ELAC, calls the coalition’s plan a “Green New Deal for Puerto Rico” that could address climate change while bringing a measure of economic justice and clean-energy job growth. Santiago also serves on Earthjustice’s Board of Trustees and recently became a member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council.

There’s money that could be used to implement this bold vision — nearly $10 billion of it. That’s the amount that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has allocated for Puerto Rico to repair the damage Hurricane Maria inflicted on its electrical grid and protect itself from future disasters.

“We could build back in a whole different way with a 21st-century electrical system, using local resources for rooftop solar on a massive scale,” says Santiago. “The $10 billion in FEMA funding is more than enough.”

What’s more, the law is on the coalition’s side. In 2019, Puerto Rico’s governor signed legislation committing the island to switch to 100% clean energy by 2050. And in August 2020, the Puerto Rican government agency in charge of regulating energy policy affirmed this vision. It adopted a long-term plan that calls for Puerto Rico to invest heavily in solar energy.

If Queremos Sol becomes reality, Puerto Rico could provide a roadmap for other areas seeking energy independence. It could also model the benefits of a distributed solar network for places like Texas, where dependence on large, centralized gas plants contributed to deadly power outages during a severe winter storm in early 2021.

However, wealthy fossil fuel interests are standing in the way.

Earthjustice attorney Raghu Murthy says U.S. fossil fuel companies are spending huge sums of money to lobby and advertise in Puerto Rico. And the board of officials in charge of deciding how to operate Puerto Rico’s largest utility has no accountability to ordinary Puerto Ricans. That’s because, after many decades of colonial oppression pushed the island into billions of dollars of debt, the U.S. Congress passed a law in 2014 that set up an unelected oversight board with sweeping power to make economic decisions for Puerto Rico.

So far, one of the board’s main strategies for cutting government spending has been to privatize public institutions, including the island’s sole electric utility. According to a 2020 investigation by The Nation, the utility’s plan involves paying two offshore fossil fuel companies $125 million a year to supply and distribute energy from oil, coal, and fracked gas. If a catastrophic storm hits the island, the companies have an escape clause, allowing them to walk away from their obligations to provide energy.

Under the board’s supervision, the utility has proposed spending large sums — including part of the FEMA fund intended to repair Puerto Rico’s grid — to build even more fracked gas infrastructure. That money is being funneled toward U.S. companies like the billionaire-led fossil fuel firm New Fortress Energy, which recently constructed a gas import terminal in San Juan.

Environmental advocate Myrna Conty says the company failed to consult with nearby communities when assessing the facility’s health and safety risks, which could include deadly explosions or fires from a gas leak. The New Fortress terminal is also adjacent to Sabana, a low-income community already subjected to pollution from nearby petroleum terminals and port traffic.

“They don’t live here. They don’t care about the environment here. They’ll go, and we’ll be contaminated and sick.”

Myrna Conty

Environmental Advocate with Alliance for Renewable Energy Now coalition

Conty, who volunteers within the coalition pushing for the distributed solar plan, believes the companies with which the utility is contracting don’t have the best interests of Puerto Ricans in mind.

“They’re going to make money off us and leave us behind,” she says. “They don’t live here. They don’t care about the environment here. They’ll go, and we’ll be contaminated and sick.”

In many cases, it’s not even possible for Puerto Ricans to learn what decisions those in power are making about the island’s energy future. Meetings have reportedly been held without public knowledge.

But at every opportunity, the coalition — with legal representation from Earthjustice — is fighting against efforts by the fossil fuel companies to keep Puerto Rico under their thumbs.

One prong of the coalition’s strategy involves shutting down the New Fortress terminal.

Under U.S. law, plans to build the terminal should have been reviewed by a federal energy commission before construction began. That never happened, because New Fortress never submitted an application.

In March, Earthjustice filed a formal complaint calling on the commission to exercise its power to close the facility. The coalition is also seeking an investigation by the Puerto Rico Legislative Assembly.

“It’s the commission’s duty to protect communities,” says Murthy, the Earthjustice attorney representing the coalition.

While the coalition works to take down a gas terminal, it’s also seeking to guide Puerto Rico’s future energy investments in a more sustainable direction. Earthjustice and partners have been meeting with Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-Ariz.) and Rep. Nydia Velázquez (D-N.Y.), who Murthy says are looking for ways to support clean energy on the island.

Grijalva and Velázquez were two of 17 senators and congressional representatives, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), who recently called on FEMA to ensure that the nearly $10 billion in recovery funds are used to bring renewable energy to the island.

There’s a long road ahead to reach the coalition’s vision for Puerto Rico. But Santiago says she believes it’s possible for Puerto Ricans to become producers, not just consumers, of energy.

“The citizens would reap the benefits of the energy system,” she says. “A radical energy system transformation is doable in Puerto Rico.”

Laura Beatriz Arroyo, senior attorney based in Miami, Florida, joined Earthjustice in 2018. Laura represents community and environmental groups in Puerto Rico as they press the government for meaningful action to transition to clean energy.

Raghu Murthy deputy managing attorney with the Clean Energy Program, joined Earthjustice in 2018. Raghu’s work is focused on challenging proposed gas plants.

Keith Rushing Earthjustice's national communications strategist for Partnerships and Intersectional Justice, is a communications professional with a passion for social justice issues. @krush526.

Earthjustice’s Clean Energy Program uses the power of the law and the strength of partnership to accelerate the transition to 100% clean energy.

The Florida regional office wields the power of the law to protect our waterways and biodiversity, promote a just and reliable transition to clean energy, and defend communities disproportionately burdened by pollution.