One Tribe’s Fight to Protect the Great Lakes

The Bay Mills Indian Community is fighting efforts to extend the life of a dangerous oil pipeline that runs through its tribal territory and one of the world’s most sensitive ecosystems.

Apr. 14, 2023

When Jacques LeBlanc Jr. was a little boy, his dad would wake him up before sunrise and drive them to Michigan’s Lake Superior. Along the way, they’d stop to buy some gas station treats — his favorite part.

Latest News

Enbridge pushes for another century of its Line 5 oil pipeline despite widespread opposition.

Once at the docks, LeBlanc’s dad, a commercial fisherman, would tuck his son into an oversized rain slicker, black rubber boots, and yellow dish gloves. They’d hop in a boat and glide through the Great Lakes, a linked chain of bottomless blue pools that together serve as one of the world’s largest freshwater ecosystems. As his father hauled in nets brimming with whitefish and lake trout, LeBlanc would run around the boat deck, grabbing at their squirmy, shimmering bodies. For every fish he placed in a wooden box, the young LeBlanc got a nickel.

“I just loved being out on the water, watching the sun rise, feeling the cold morning mist on my face,” he says. “It’s a feeling that stuck with me my whole life.”

It wasn’t until years later that LeBlanc learned about a threat at the bottom of the lakes — one that could destroy the entire region, and the spiritual epicenter of LeBlanc’s people, the Anishinaabe.

LeBlanc knew he had to step in to protect the Great Lakes, as well as his tribe’s way of life, before it was too late.

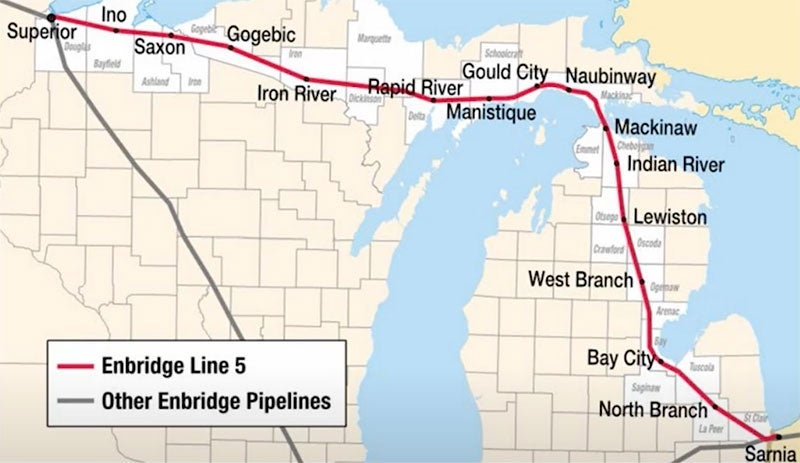

The Enbridge Line 5 pipeline, built in 1953, pumps up to 540,000 barrels of petroleum per day through the Great Lakes region. As it travels from northwest Wisconsin, through Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsulas, ultimately ending in Canada, Line 5 crosses woods and wetlands connected by more than 300 rivers and streams.

Yet nobody really paid much attention to Line 5 until 2010, when another pipeline operated by Enbridge ruptured in Michigan, releasing more than a million gallons of toxic crude oil into nearby waterways. It was the worst pipeline oil spill in U.S. history. For months, the Kalamazoo River ran black, coating animals with oil, polluting more than 4,000 acres of land, and closing the river to public and recreational use for nearly two years.

Michiganders soon turned a critical eye to Enbridge’s other pipelines across the state, which suffer an average of one oil spill every 20 days. Michiganders were particularly concerned about a rundown section of the Line 5 pipeline that cuts through the Straits of Mackinac, an environmentally sensitive waterway connecting Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. Gaps were discovered in the Line 5’s protective coating. And after decades of erosion, the pipeline no longer lies on the lakebed as it crosses the Straits. Instead, it floats, making it easier for boats traveling above to snag their anchors on the pipeline below, potentially rupturing it and releasing oil. It’s like a fingernail catching on a loose piece of thread — except instead of ruining a sweater, you ruin a priceless ecosystem. According to a report from the Michigan Technological University, a worst-case Line 5 spill could cause $1.8 billion in damages and spoil more than 400 miles of Great Lakes shoreline.

It wasn’t long before a movement began to build against Line 5. But rather than remove the section that crosses the Straits entirely, Enbridge proposed building a new segment of pipeline to go through a tunnel. While the proposed tunnel undergoes permitting and construction, which could take years, Enbridge wants to keep oil flowing. In addition, the tunnel would come with a 99-year lease to continue operating the pipeline, locking a world in climate crisis into further dependency on fossil fuels.

In early 2019, state officials sought to push back against Line 5 with lawsuits and an executive order. Against this uncertain legal backdrop, Enbridge began applying for state and federal permits to build the tunnel.

But there was one group of people the company never asked for permission: those who lived in the Straits of Mackinac region long before Enbridge, long before the oil pipelines, and long before the state of Michigan was originally formed. And they’re still here today, fighting for their way of life.

Since time immemorial, the Anishinaabe have made the Great Lakes their home, living in harmony with the natural environment. The region is also the center of an Anishinaabe creation story, and it continues to be a place of ongoing spiritual significance to the Anishinaabe people.

In 1836, facing sustained violence and pressure from colonial settlers, the Anishinaabe ceded nearly 14 million acres of the tribe’s territory to the federal government. In exchange, the Anishinaabe reserved the right to fish, hunt, and gather in the ceded area in perpetuity. Today, most members of the Bay Mills Indian Community — a modern-day successor of the Anishinaabe — rely on fishing for at least part of their annual income.

Bryan Newland, a former president of Bay Mills, credits the tribe’s longstanding efforts to uphold its treaty rights as his inspiration for becoming a public interest lawyer.

“Growing up, I heard all kinds of stories about people in the community who helped make things better here,” says Newland. “I decided to go to law school to make things better, too.”

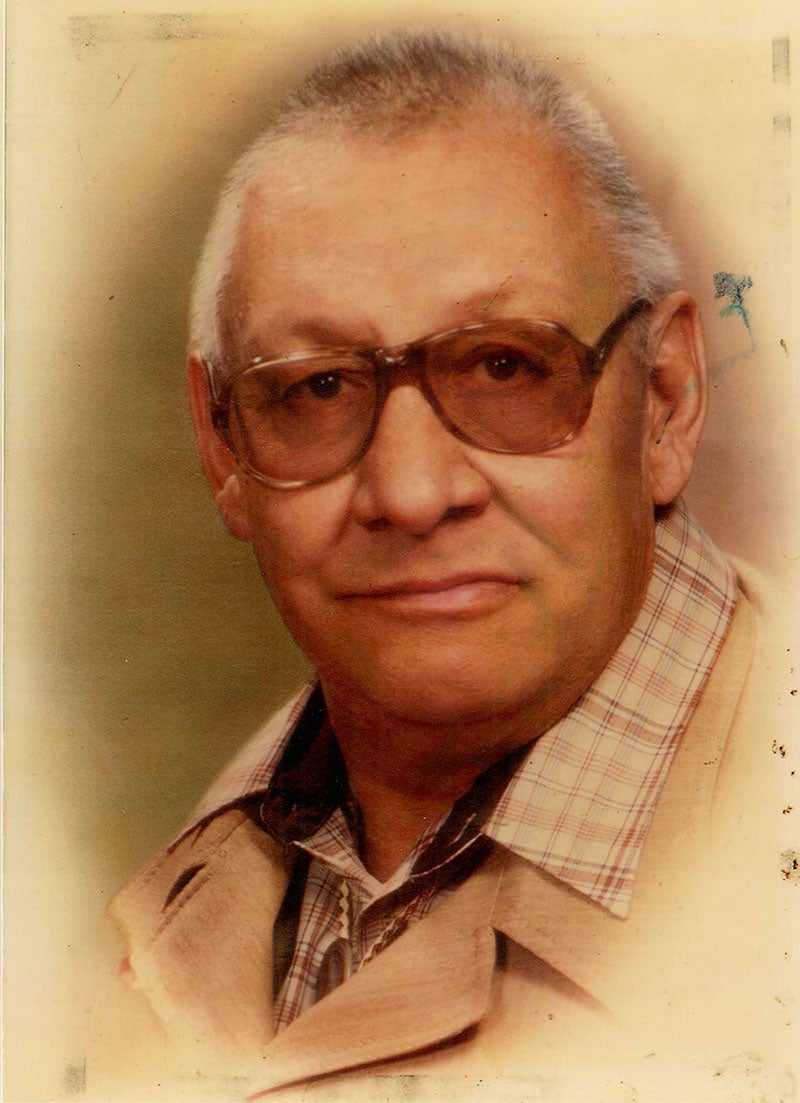

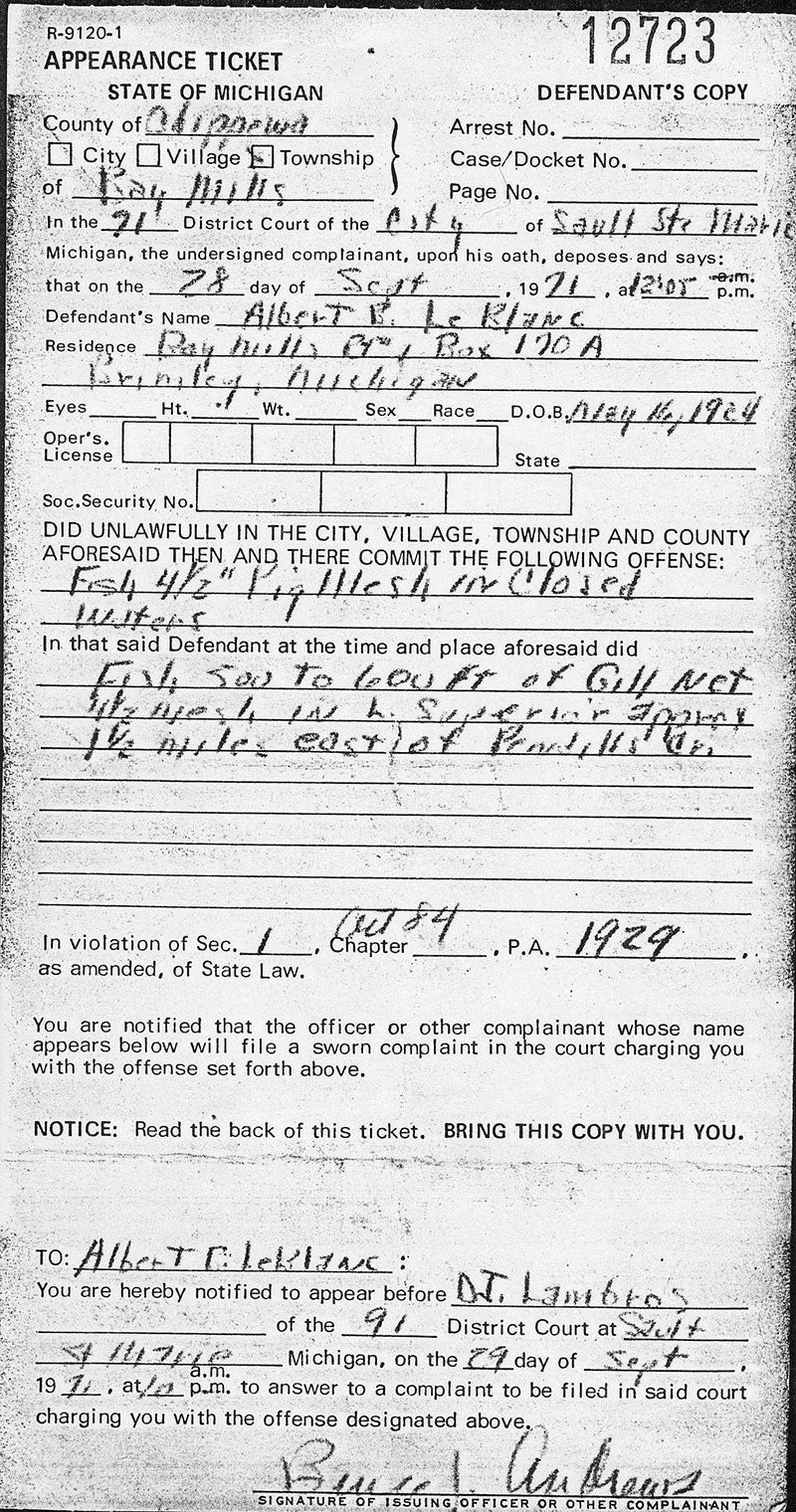

One story Newland often heard was about a court battle with the federal government in 1976 over the tribe’s use of its traditional fishing gear. The landmark case began after a Bay Mills member purposefully set a gill net — deemed illegal by the state but used by tribal fishers for generations — into Lake Superior and then called the authorities. Though he was issued a citation, a court ruling later re-asserted the tribe’s federally protected treaty rights as the supreme law of the land.

The man who called the authorities that day was “Big Abe” LeBlanc, Jacques LeBlanc Jr.’s grandfather.

As a third-generation fisherman and member of the tribe’s Conservation Committee, LeBlanc sees everyday how climate change, invasive species, chemical pollutants, and habitat destruction harm the waters that sustain his livelihood. But he believes that the most obvious and preventable risk to the Great Lakes is the Line 5 pipeline.

LeBlanc says that other big environmental battles across the country, like the Dakota Access pipeline, the Kalamazoo spill, and the Flint water crisis, have sparked a broader conversation among the Bay Mills Indian Community and other tribes about how to fight these threats in a historically unjust system.

Ultimately, says LeBlanc, these fights are about balance, and profit-driven companies like Enbridge don’t have that balance.

“When we signed those treaties, we wanted to ensure that our people could always have a resource to have a way of life and make a living and get some food,” he says. “That’s all it’s ever been about.”

“When we signed those treaties, we wanted to ensure that our people could always have a resource to have a way of life and make a living and get some food.”

Jacques LeBlanc Jr.

Third-generation fisherman and member of the Bay Mills Tribe’s Conservation Committee

While Bay Mills weighed its options for fighting Line 5, Enbridge was moving full speed ahead, filing permits in the spring of 2020 among various regulatory agencies. Bay Mills decided it was now or never. The community wanted to stop or slow down the project, and it needed all the help it could get.

Bay Mills’ leadership reached out to both Earthjustice and the Native American Rights Fund, who have filed lawsuits against the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines, respectively, on behalf of tribal clients. The two nonprofit legal organizations, which worked together in the past, decided to pool their resources.

“Ultimately our organization was created to serve Indian Country,” says David Gover, an attorney at NARF. “That's our North Star, to make sure that underrepresented communities are represented to the best of our abilities.”

He adds that the Enbridge project is part of a larger pattern of the federal government’s failure to consult with tribes and protect treaty rights when considering massive infrastructure projects throughout Indian country.

In August 2020, Bay Mills intervened in Enbridge’s permit application before the Michigan Public Service Commission, becoming the first Tribal Nation to do so. They were soon joined by several neighboring tribes. Since then, Bay Mills has given powerful testimony on the distinct cultural, spiritual, and economic interests threatened by Line 5.

Enbridge has fought to keep the Michigan Public Service Commission from listening to tribal voices, successfully striking some of Bay Mills’ testimony from the record. However, it couldn’t quiet the concerns flagged by two separate engineers, who've identified the serious risk of an explosion in the tunnel that could release oil and devastate the freshwater, wildlife, and shorelines of Great Lakes.

In late 2020, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer delivered a huge blow to Line 5 by revoking Enbridge’s original easement for operating in the Straits of Mackinac, citing an unreasonable risk to the Great Lakes and to tribal communities. In May 2021, Bay Mills added even more pressure by passing a rare and permanent action to banish Enbridge from its reservation. And in July 2022, the Commission requested more information from Enbridge about this risk and other safety issues with the current Line 5 pipeline.

Earthjustice attorney Christopher Clark says that regulators and legislators are right to take a closer look at the risks of the tunnel project.

“It’s important for us to show that the tunnel project poses unacceptable risks to Bay Mills and to everyone who relies on the Great Lakes. The Straits of Mackinac is simply not the place to experiment with a hazardous pipeline, and especially not by a company as untrustworthy and disastrous on safety as Enbridge has been,” says Clark.

In addition to intervening at the commission, Bay Mills and Earthjustice requested meetings with other permit-issuing agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy. Federal and state law requires such agencies to meaningfully consult with tribes.

The key word here is “meaningful,” says Bay Mills President Whitney Gravelle. She says the consultation process with regulatory agencies often feels like a vent session for tribes, where the regulatory agencies rubberstamp their approvals despite tribal concerns.

“They’ll sit down at a table with you and they’ll say, ‘All right, tell us what you think,’” she says. “Then you tell them, and they respond, “All right, thanks, bye.’ They don't ever seriously listen.”

“To see that kind of support coming from the state felt really good for all of us trying to defend our waters and our tribal rights,” says LeBlanc.

So far, Enbridge has refused to comply with the governor’s order and the Tribe’s wishes. But the public and legal pressure continues to grow. In addition to representing Bay Mills, Earthjustice is also representing the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa in its advocacy against federal and state regulatory permits allowing another part of Enbridge’s pipeline to re-route around and upstream of the Band’s reservation and through the treaty ceded territory of the Band and other Ojibwe tribes. The Line 5 pipeline currently crosses the Bad River Band’s reservation.

In September 2022, a federal judge in Wisconsin ruled that Enbridge is trespassing on the reservation by continuing to operate Line 5 despite the Band not renewing Enbridge’s easements. And in March 2023, the Army Corps delayed its environmental review of Line 5 after serious concerns were raised by Bay Mills, other tribal nations, the EPA, and thousands of other concerned individuals and Earthjustice supporters. Finally, the company faces criminal charges for puncturing an underground aquifer in Minnesota during its shoddy construction of Line 3, a pipeline that Earthjustice challenged in partnership with several Tribal Nations and the Sierra Club.

Though the fight continues, for now, LeBlanc is relieved to see his voice had an impact and is ready for the fight ahead.

“Hearing the legends of my grandfather, Big Abe, and the issues he brought forward when he thought something needed to be done, that resonates really strongly with me,” says LeBlanc. “I have a responsibility to protect our resources and Mother Earth, and I'm not going anywhere anytime soon. As long as I have a breath in me, I will continue to try to fight that good fight.”

Take Action:

Originally published in 2021.

Jessica A. Knoblauch is a senior staff writer at Earthjustice. Her goal is to bring to life Earthjustice’s inspiring and crucially important environmental litigation work through engaging storytelling.

Earthjustice’s Midwest office works to partner with and support communities and Tribes fighting for environmental and climate justice. We also aim to protect our region’s precious places and wildlife, and build sustainable energy and climate solutions.

We fight to ensure our tribal and Indigenous clients’ natural and cultural resources are protected for future generations.