Court Gives Grizzlies Something To Sleep On

In an ecosystem where all life is interrelated and connected, the decline of one life form can precipitate the decline of another. In other words, as the whitebark pine seeds go, so go the Yellowstone grizzlies. In November 2011, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a ruling that reinstated Endangered Species Act protections for

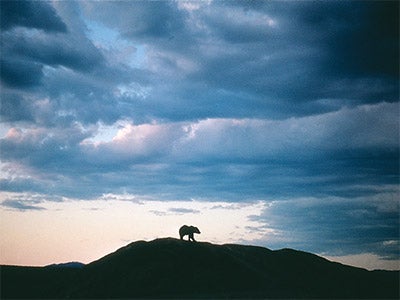

As they settle into their dens for a long winter’s nap, Yellowstone’s grizzly bears can hibernate in peace—thanks to an appeals court ruling in November that keeps them protected by the Endangered Species Act.

In 2007, the Bush administration erroneously considered Yellowstone’s grizzly bear population recovered enough to be taken off the endangered species list. Earthjustice attorneys convinced a court to overturn that decision in 2009 and return the bears to “threatened” status, a ruling the federal government challenged. Earthjustice promptly defended against the challenge.

Now, two years later, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has ruled that grizzlies in the Yellowstone region still require protections afforded by the Endangered Species Act.

The decision secures protections for an estimated 540–660 threatened grizzlies in the Yellowstone ecosystem in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho. The federal government desired to turn management of the grizzlies over to state wildlife agencies and permit hunting of the bears.

“If we want to protect the grizzlies of Yellowstone, we have to confront squarely the loss of whitebark pine,” said Doug Honnold, managing attorney for Earthjustice’s Northern Rockies office.

Grizzly bears, as you might guess, need a lot of food. In Alaska and other coastal areas they gorge on salmon runs every summer and fall. But the bears in the Yellowstone area have no salmon and must survive by eating a diet primarily of grasses, bulbs, bugs, elk, trout and especially the seeds of the whitebark pine tree.

Whitebark pine seeds are to a grizzly bear what macadamia nuts or pecans are to humans. The highly nutritious seeds are chocked full of fat and protein, and when available, are eaten by the thousands by Yellowstone grizzlies. But global warming has allowed bugs known as mountain pine beetles to move up the mountainsides, and attack and kill millions of acres of whitebark pine forests. As a result, the bears are forced to move down the mountain in search of different foods, where they often run into conflicts with humans and are killed.

A 2009 survey showed that 51 percent of the whitebark pine forests in the Greater Yellowstone area have already suffered high mortality from mountain pine beetles, with another 31 percent experiencing significant mortality. This year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that whitebark pine itself is an endangered species.

In an ecosystem where all life is interrelated and connected, the decline of one life form can precipitate the decline of another. In other words, as the whitebark pine seeds go, so go the Yellowstone grizzlies.

Starting in 2008, the number of documented Yellowstone grizzly bear mortalities jumped to about 50 per year—the highest rate of mortality since the listing of the bears as a threatened species in the lower-48 states in 1975. In 2009, 31 documented grizzly deaths were reported, and in 2010 deaths climbed back to 50. By late November 2011, 42 bears had already died.

With the effects of global warming being felt more acutely each year, Yellowstone’s grizzlies still face a long road to recovery, but the court’s ruling at least offers the bears a fighting chance.

First published in the Earthjustice Quarterly Magazine, Winter 2011 issue.