The neurotoxic pesticide harms children and the environment. There are no safe uses for chlorpyrifos.

For half a century, staple food crops in the United States — such as wheat, apples, cherries, and citrus — were sprayed with chlorpyrifos, an organophosphate pesticide that can permanently damage the developing brains of children, causing reduced IQ, loss of working memory, and attention deficit disorders.

But in a series of lawsuits, Earthjustice, alongside other groups, succeeded in 2021 to getting the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ban chlorpyrifos from food. This ban lasted less than two years, however, due to a chemical manufacturer and agrobusinesses’ legal pushback.

Indeed, shortly after the ban, Gharda Chemical International, along with over a dozen agricultural trade groups, challenged the EPA's ban, leading to the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals partially overturning the ban in 2023. As a result, chlorpyrifos can be sprayed once more on our fruits and vegetables, as the EPA works in addressing the court’s decision.

Rather than committing to reinstating the full ban, the EPA said it plans to maintain food uses for roughly half of the historically submitted applications, which include apples, asparagus, cherries, citrus, cotton, peaches, soybeans, sugar beets, wheat, and alfalfa. This official decision is anticipated later in 2024.

What is chlorpyrifos?

Chlorpyrifos (pronounced: klawr-pir-uh-fos) is a neurotoxic pesticide in the organophosphates class of chemicals. Organophosphates were developed by the Nazis for chemical warfare and later adapted for commercial pesticide use after the break-up of the Nazi chemical apparatus.

Before the ban, chlorpyrifos was widely used in U.S. agriculture to kill a variety of agricultural pests.

Chlorpyrifos is acutely toxic and associated with neurodevelopmental harms in children. Prenatal exposures to chlorpyrifos are associated with lower birth weight, reduced IQ, loss of working memory, attention disorders, and delayed motor development.

Acute poisoning suppresses the enzyme that regulates nerve impulses in the body and can cause convulsions, respiratory paralysis, and, in extreme cases, death. Chlorpyrifos was one of the pesticides most often linked to pesticide poisonings. (Read an in-depth report on chlorpyrifos.)

How are people exposed to chlorpyrifos?

Through residues on food and in drinking water, and by toxic spray drift from pesticide applications

People are exposed to chlorpyrifos through residues on food, drinking water, and by toxic spray drift from pesticide applications.

Farmworkers are exposed to it from mixing, handling, and applying the pesticide, as well as from entering fields where chlorpyrifos was recently sprayed.

Residential uses of chlorpyrifos for insect control ended in 2000, after EPA found unacceptable risks to kids. Communities continue to be exposed to chlorpyrifos through drift from spraying and farmworkers unknowingly carrying this poison home, as pesticides can cling to workers’ clothing. What is more, as chlorpyrifos uses start up again, so will exposure overall, particularly in rural areas.

Meanwhile, children experience greater exposure to chlorpyrifos and other pesticides, because they frequently put their hands in their mouths, and relative to adults, they eat more fruits and vegetables and drink more water and juice for their weight.

Why do we need to ban chlorpyrifos?

There are no safe uses for chlorpyrifos

A growing body of evidence shows that prenatal exposure to very low levels of chlorpyrifos — levels far lower than what EPA was previously using to establish safety standards — harms babies permanently.

Peer-reviewed studies that have tracked real-world exposures of mothers and their children to chlorpyrifos have associated the pesticide these types of harm.

EPA released a revised human health risk assessment for chlorpyrifos in 2016 — its own assessment designed to protect children from these types of neurodevelopmental harm — that confirmed that there are no safe uses for chlorpyrifos. EPA found that:

- All food exposures exceed safe levels, with children ages 1–2 exposed to levels of chlorpyrifos that are 140 times what EPA deems safe.

- There is no safe level of chlorpyrifos in drinking water.

- Pesticide drift reaches unsafe levels at 300 feet from the field’s edge.

- Chlorpyrifos is found at unsafe levels in the air at schools, homes, and communities in agricultural areas.

- All workers who mix and apply chlorpyrifos are exposed to unsafe levels of the pesticide, even with maximum personal protective equipment and engineering controls.

- Farmworkers are allowed to re-enter fields within 1–5 days after pesticide spraying, but unsafe exposures continue on average 18 days after applications.

Farmworkers and their families, particularly children, are most affected by this toxic pesticide. In addition to food exposures, they are more likely to have contaminated drinking water, and they are, quite literally, getting hit from all sides by drift exposures at schools, daycares, on the playground, at work, and in their homes. Because farmworkers tend to be Latino and low-income, the impacts of chlorpyrifos disproportionately impact communities of color.

In this video, agricultural worker Claudia Angulo describes how her son Isaac suffered brain damage after she was exposed to chlorpyrifos during pregnancy. Since Isaac’s diagnosis with ADHD, she has worked to raise awareness among farmworkers, the public, and politicians about the chemical's health effects.

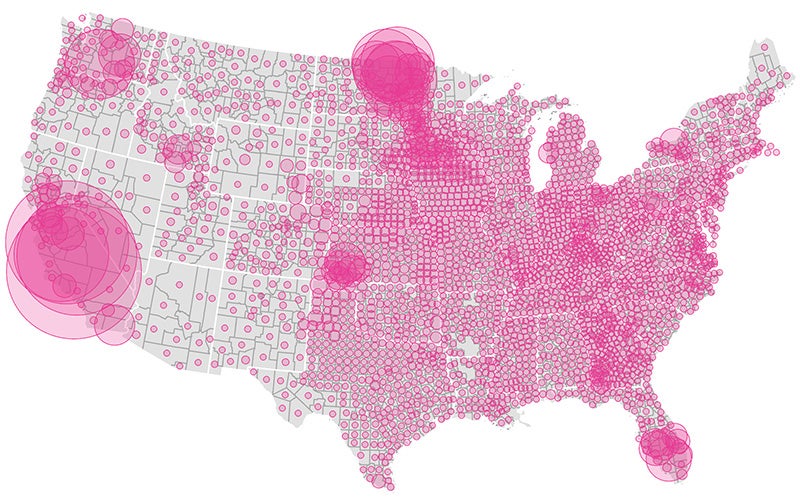

Which crops have chlorpyrifos on them?

Apples, oranges, wheat, citrus, and more

Chlorpyrifos is used on a wide variety of crops including apples, oranges, wheat, citrus, and other foods children eat daily.

More than half of all apples and broccoli in the U.S. were sprayed with chlorpyrifos before the ban.

Chlorpyrifos is also used on feed crops that lead to residues in milk, eggs, and meat.

USDA’s Pesticide Data Program found chlorpyrifos residue on citrus even after being washed and peeled. By volume, chlorpyrifos was most used on soybeans and alfalfa crops with one million pounds or more applied annually to each crop.

What does the law require?

To protect children from unsafe exposures to pesticides

The 1996 Food Quality Protect Act — passed unanimously in Congress — requires EPA to protect children from unsafe exposures to pesticides. The FQPA requires EPA to ensure with reasonable certainty that “no harm will result to infants and children from aggregate exposure” to pesticides. EPA cannot take industry costs into consideration when protecting children from harmful pesticides, because FQPA is a health-based standard.

If EPA cannot ensure that a pesticide won’t harm children, the law requires EPA to ban uses of the pesticide.

Congress strengthened protections for children from pesticides following the release of a pivotal 1993 report by the National Academy of Sciences. The NAS report criticized the EPA for treating children like “little adults” by failing to address the unique susceptibility of children to pesticide exposures based on the foods they eat, their play, and sensitive stages of development.

Jim Cochran, a strawberry farmer, was poisoned by pesticides. People told him no one cared about healthy food and healthy workers. He decided to prove them wrong. More on Jim's story.

What legal actions have been taken?

Many. Earthjustice and our clients, alongside many other groups, have worked for more than a decade to build the case to push the EPA to ban chlorpyrifos.

In 2007, Pesticide Action Network and Natural Resources Defense Council filed a petition with EPA, seeking a chlorpyrifos ban based on the growing evidence of how it harms children.

Seven years later, following several lawsuits and delays, EPA had still not acted on the petition. In September 2014, on behalf of PAN and NRDC, Earthjustice filed a lawsuit in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals to compel EPA to act on the petition.

Our Clients

League of United Latin American Citizens; Pesticide Action Network North America; Natural Resources Defense Council; California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation; Farmworkers Association of Florida; Farmworker Justice; Greenlatinos; Labor Council for Latin American Advancement; Learning Disabilities Association of America; National Hispanic Medical Association; Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste; United Farm Workers

The following year, the court called EPA’s delays “egregious” and ordered EPA to act on the petition by Oct. 31, 2015. By that deadline, EPA proposed to ban chlorpyrifos on food. The court gave EPA until Mar. 31, 2017, to take final action. However, despite the overwhelming evidence that the pesticide harms children, workers and the environment, the EPA issued a decision refusing to ban the pesticide, because the agency wanted to continue studying the science.

Earthjustice challenged that decision both through an administrative appeal to EPA and in court. New York, California, Washington, Massachusetts, Maine, Maryland, and Vermont filed their own appeals, also calling for a ban.

On Aug. 9, 2018, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in the case, finding that EPA must finalize its proposed ban on chlorpyrifos within 60 days, based on undisputed findings that the pesticide is unsafe for public health, and particularly harmful to children and farmworkers. EPA obtained a re-hearing before an 11-judge 9th Circuit panel, which ordered EPA to rule on the administrative appeal seeking a chlorpyrifos ban by Jul. 18, 2019. By that deadline, EPA announced, again, that it would continue to allow this harmful pesticide to stay in our fruits and vegetables.

Earthjustice brought the EPA back to court, challenging that decision and seeking a ban on chlorpyrifos. In April 2021, the 9th Circuit held that EPA had violated the law by allowing chlorpyrifos to be used on food without finding it safe for children. The court doubted whether EPA could find chlorpyrifos safe given its extensive findings that chlorpyrifos is associated with learning disabilities in children from low-level exposures.

In its decision, the court noted:

“EPA has had nearly 14 years to publish a legally sufficient response to the 2007 Petition (to ban chlorpyrifos). During that time, the EPA’s egregious delay exposed a generation of American children to unsafe levels of chlorpyrifos. By remanding back to the EPA one last time, rather than compelling the immediate revocation of all chlorpyrifos tolerances, the Court is itself being more than tolerant. But the EPA’s time is now up.”

The court gave the agency 60 days from the end of the case to act. In August 2021, EPA revoked all chlorpyrifos tolerances, which prohibited its use on food. The ban went into effect on Feb. 28, 2022. For the first time since 1965, children and farmworkers across the country were finally spared needless poisonings and lifelong learning disabilities from chlorpyrifos. The ban remained in place through the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons.

What’s happening now?

While Dow Agrosciences (now Corteva) and other U.S. companies stopped selling chlorpyrifos, Gharda Chemicals International challenged the ban, along with agribusiness groups.

On Nov. 2, 2023, the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the EPA’s 2021 rule that banned the use and presence of chlorpyrifos on the foods we eat. The 8th Circuit held that the EPA had to consider whether it could find 11 uses safe, based on a 2020 EPA risk assessment that had abandoned the agency’s efforts to protect children from learning disabilities. Scientists, public health groups, farmworkers, and others had submitted comments criticizing the 2020 assessment for failing to protect children, but EPA has never addressed those comments.

“We are profoundly saddened by the 8th Circuit’s decision to send the chlorpyrifos ban back to the EPA to review, which will subject farmworkers and children to this extremely harmful pesticide yet again,” said Patti Goldman, attorney at Earthjustice.

“Food crops have been successfully grown in the two years since chlorpyrifos has been banned.”

In December 2023, the EPA announced that it would not seek further review in the courts of the 8th Circuit decision, because it believed it could put protections in place faster than would occur through the courts. The EPA stated that it would “expeditiously propose a new rule to revoke the tolerances associated with all but the 11 uses referenced by the court.”

The EPA has not yet done so, and recently projected that it would release the proposal in the summer of 2024 and finalize it by the end of 2024.

In the meantime, chlorpyrifos can be used on all the food crops that had been subject to the ban.

As for the 11 uses that EPA’s weakened 2020 risk assessment indicated might be safe, EPA does not plan to respond to the public comments and release an amended proposal until 2025, with final action delayed until later that year.

The 11 crops are:

alfalfa

apple

asparagus

cherry

citrus

cotton

peach

soybean

strawberry

sugar beet

wheat

but only in certain areas of the country and subject to limitations on application rates and methods. The EPA has put none of those limitations into place nor has it instituted measures to protect farmworkers from the harmful exposures the EPA has consistently documented beginning in 2014.

Earthjustice, our clients, and partners are outraged and saddened that it is taking the EPA so long to protect children from neurodevelopmental harm caused by exposure to chlorpyrifos.

Several states have already banned chlorpyrifos, namely Hawaiʻi, Maryland, New York, Oregon, and California. Farmworkers and children will be protected from exposures in those states, but they — like everyone else — will be exposed to chlorpyrifos residues on food until the EPA re-institutes national food safety rules.

What you can do: Demand decisive action from the federal government — tell the EPA to follow the agency’s mandate to protect children and reinstate the chlorpyrifos ban.