Ecology Without Equality

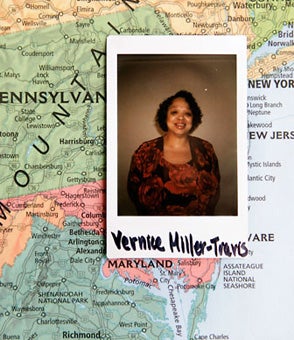

Environmental justice advocate and former 50 States Ambassador, Vernice Miller-Travis, discusses why the fractured nature of green groups and the environmental justice movement undermines our overall political effectiveness.

Environmental justice advocate Vernice Miller-Travis discusses why the fractured nature of green groups and the environmental justice movement undermines our overall political effectiveness.

Vernice Miller-Travis is a longtime environmental justice advocate and co-founder of WE ACT for Environmental Justice, a northern Manhattan community-based organization. She believes that green groups and environmental justice groups must work together in order to build a more diverse and effective environmental movement.

Vernice spoke with Jessica Knoblauch, content producer at Earthjustice, in January 2013.

Jessica Knoblauch: Vernice Miller-Travis, welcome to Down to Earth. You’ve spent almost three decades as a leading activist in the environmental justice movement. What first inspired you to get involved in environmental justice issues?

Vernice Miller-Travis: Well, I went to work as a research assistant at the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice. At the time United Church of Christ, the Protestant denomination, was based in New York City. And it had a civil rights arm called the Commission for Racial Justice that had worked on civil rights issues since the civil rights movement and were about to undertake a research project called the “Special Project on Toxic Injustice,” which was being led by the research director at the time, a man named Charles Lee. Charles Lee is now an official at EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency], directing the environmental justice work at EPA. And once he described the research project to me I was like, “Wow, this is amazing!” I had no idea that there was a relationship between racial discrimination and the location of hazardous waste sites and the impact of those hazardous waste sites on the people who live nearby.

I just had no idea and so I jumped at the chance to go and do that work for Charles Lee. And then—this is in 1986—about a month later I met some folks who lived in the community where I lived in West Harlem, New York, who were fighting the siting of the North River Sewage Treatment Plant right on the edge of the community at the Hudson River. And the two things sort of merged. So I wound up being there as this conversation really began to pick up steam, and our research at the United Church of Christ would ultimately come forward in a report that we wrote and published called Toxic Waste and Race in the United States. And that was the first report to look comprehensively at the relationship between race and waste, and the conversation really took off from there, as it were.

Jessica: I see, and so you mentioned the North River Sewage Treatment Plant in Harlem. This area had the highest premature death rate from asthma of any community in the western hemisphere. Can you talk a little bit about some of the lessons you learned during that first struggle?

Vernice: Oh my goodness. Wow. It’s like a bible! From that first struggle, I really sort of set the foundations for most of my work going forward over these last two and a half decades. I learned that lay people can learn any subject matter that they need to: environment, science, natural resources, public health, air pollution policy. They can rise to the occasion and learn whatever is necessary when their lives are in danger, when their community is under threat, when their families are not safe.

People can absorb information, can learn it, and can become extraordinarily sophisticated advocates on their own behalf once they realize what the challenge is and what the information is being brought to the community. And so I think there’s a standard thinking that you have to be an expert. You have to have a college degree or an advanced degree in order to be an environmentalist. That’s not the case. So I learned that.

People can absorb information, can learn it, and can become extraordinarily sophisticated advocates on their own behalf once they realize what the challenge is and what information is being brought to the community.

I learned that there is an intimate relationship between local land use and zoning and environmental threats and hazards, particularly in communities of color, where local government, over time, has really set in place a practice of residential segregation, as it were. And it really comes from that period in our history when people of color were segregated as to where they could live, and often where they were forced to live were places that were ecologically sensitive or unsafe. And so that was the case in the 1940s and 50s, but it’s still the case in the 21st century. And the legacy of those decisions continues to harm and shape the outcome of people’s lives.

So that’s how we came to be a community that had a number of polluting facilities in it. We had highways on three sides of our community. The majority of the bus depots were located in our community and in northern Manhattan. So we had this concentration of diesel sources of pollution, and those concentrations of sources of pollution were what led to the high rates of asthma and asthma morality in our community. But nobody had made that connection before we really started to look into it. And we started to look into it because there were so many sick people in our community and so many families that were being burdened by asthma and death from asthma.

And I also learned that I needed to be an urban planner because the source of our problems was what was happening with local land use and zoning. And so I went to graduate school to pursue a degree in urban planning because I felt that if you really want to get to the bottom of environmental injustice, then you have to understand this relationship between race, land use and zoning, and the placement and operation of facilities that adversely affect environmental quality and public health.

Jessica: Interesting. And as you mentioned, race has proved to be the single most statistically significant indicator of the location of hazardous waste sites, so stuff like this is something that people did not realize until groups such as your organization started to look into this issue?

Construction of the North River Treatment Plant. The plant was originally not intended to include pollution control systems or devices. (Hope Alexander / EPA)

Vernice: Many people suspected it. The local dump in any town was where people of color, poor people, and/or immigrant communities lived. The incinerator was where these communities existed. Highways would be built right through these communities. Sometimes communities would be destroyed and uprooted to build new highways and byways. All the adverse things were in the places where this population of people lived, in any community, in any town, in any city, anywhere in the United States of America.

And that was what our report, Toxic Waste and Race, really showed is that this was a national phenomenon, and that the degree of statistical significance of the relationship between race and the location of hazardous waste sites shows that these were not random occurrences, but rather intentional planning that put these facilities next to, adjacent to, or inside the places where these populations of people lived. And that was really groundbreaking analysis. But, on the other hand, my grandmother was fond of telling me that the work that I was doing was documenting something that everybody who lived in Harlem could tell you. That, it was sort of funny, but it was sort of not funny.

Jessica: So you’ve worked with the federal EPA for several years as an environmental justice advocate. How has your relationship with the EPA evolved over the years?

Vernice: Well, you know, what an excellent question. It has been a learning experience for me. I would say that when I first began to interact with EPA, which was in the late 1980s in New York, there was no group of people that I was more furious at on a consistent basis. The reason for that was when I began to really look into the land use and siting history of the North River Sewage Treatment Plan, one of the main entities that has worked to help clean up the quality of the water in the lower Hudson River in New York City, New York Metropolitan area. The plant is half a mile long, six stories high, and designed to treat 180 million gallons of raw sewage every day. And, it would change our lives forever but they had never intended to put any pollution control systems or devices on the plant. So what we got was a half-mile long, six-story high giant toilet bowl. So our community basically smelled like raw fetid sewage for a number of years until we eventually sued the city of New York and the state of New York and got them to fix the sewage treatment plant.

But the reason that I was angry at EPA is because when you look back through the historical documents about the siting and design and construction of that plant, EPA Region 2 would give the City of New York twice findings of no significant impact, that they didn’t think the sewage treatment plant would have any significant impact [on the lives of the 100,000 people who lived in West Harlem].

It utterly undermined and transformed the lives of the 100,000 people who lived in the West Harlem community. So I was furious at EPA, just you know, I mean seeing red every time I would be in a dialogue with them because I thought that they had just completely dismissed the value of the lives of the people who lived in our community.

Members of Latinos United for Clean Air speak at a Sacramento EPA hearing on regulation of fine particle pollution in July 2012. (Chris Jordan-Bloch / Earthjustice)

Over the years, I have come to know a lot of people at EPA. I especially work closely with a lot of people at headquarters in a variety of program offices but particularly in the office of environmental justice and began to, at some point, sort of change my thinking about the people who worked at EPA to recognize that they were really dedicated environmental professionals themselves who were really trying to work to improve the quality of everyone’s life in this country. And, that they needed some education and they needed some sensitizing to the issues that we now know as environmental justice but that they were not actively trying to undermine the quality of our lives.

So that was a huge learn for me and a huge transformation of my thinking about the agency and the people who worked there. And now I’m literally—and I know this is going to sound like such a cliché to your audience—but I really do have a lot of really close personal friends who work at EPA [laughs] and who I have worked with on just a number of policy issues over the decades. And they are some really good people who work there, but they still have learning to do. And so I have committed to being a part of that team of folk who help to broaden and expand the staff of EPA’s understanding of what these issues are, the complexity and multi-dimensions of these issues and the kind of approach that’s needed to be taken by the federal Environmental Protection Agency to really resolve these really somewhat intractable environmental and public health issues that are besetting a number of communities of color, low income, tribal, immigrant communities across the United States. There’s still work to be done, but so much progress has been made.

Jessica: Do you feel like the appointment of Lisa Jackson to the role of EPA Administrator, did that have a positive effect on the agency’s commitment to environmental justice?

[The appointment of Lisa Jackson] had a transformative effect on the agency’s commitment to environmental justice.

Vernice: It had a transformative effect on the agency’s commitment to environmental justice. In fact, Lisa Jackson has trail-blazed a path that no one else has been on until she got there. Now, there has been lots of work done, lots of conversations. But when Lisa Jackson got there, the whole effort around environmental justice was invested in at a level that had never happened before. Her level of personal commitment has been unequaled, and she has driven an agenda within EPA and across the federal government. It’s not just the EPA that she’s impacted.

She has helped lead an effort to really address the disproportionate impact of pollution borne by communities of color, low income, tribal, immigrant communities. She has taken it to a whole other level. And in fact it is with deep regret that we see her not intending to continue as EPA administrator for the second Obama administration. We can only hope that the level of commitment and integration of environmental justice that she has brought forward into EPA is going to continue, but she certainly has been a champion like no one before her. We hope that she has set the bar for what it will be like going forward, but she has just been extraordinary, and the many conversations, the many efforts, Plan EJ 2014, for example, which is an across-agency, comprehensive plan to integrate environmental justice into the fabric of how EPA does its work and goes about doing its work, that is her legacy, and she has just been extraordinary.

Lisa P. Jackson headed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during President Obama’s first term in office. (The National Academy of Sciences)

And I don’t think any of us anticipated the level and depth of her commitment before she became the administrator. But she has really put us in a different place, and we hope that we will stay on that trajectory and keep making progress to improve the conditions in these communities and improve the quality of life of people in EJ [environmental justice] communities across the country.

What I know has influenced her is growing up in New Orleans, and New Orleans is like a petri dish for environmental injustice. Everywhere you look there are examples of how African American, Latino, Asian American, Native American, the low-income white communities have been treated unequally and have borne the brunt of decades, if not centuries, of bad land use and bad planning, right, urban growth and development, paving over bayous and other natural systems that kept New Orleans and kept that very important delta in the Gulf of Mexico functioning and operating ecologically.

We’ve done a lot of things in terms of development over the decades, over the centuries, that have made New Orleans a really difficult place to live in. But it was particularly difficult for people of color, Native Americans, poor people, and I think her growing up in that community, in that city, in that environment, brought a level of sensitivity to her work as the EPA Administrator that you just can’t teach. So that combined with her expertise as a chemical engineer, I think it just made her uniquely qualified to serve as the EPA Administrator. And when she talks about environmental justice, when she talks about changing environmentalism as we know it, you notice she means that in her heart and in her soul, right. It’s not just talking points.

I think many green groups continue to see environmental justice issues as sort of a lesser set of environmental issues … and that sort of marginalization of those issues and the communities for whom those issues are incredibly important continues to happen.

Jessica: That’s a really good point. I mean the place that you grow up in definitely has an effect on the rest of your life, and you can see that with Lisa Jackson. So you’ve worked with groups like Earthjustice for a long time now in helping to diversify the environmental movement and bring environmental justice issues to the forefront of these organizations. What do you believe green groups are doing wrong on environmental justice, and what are they doing right?

Vernice: Well, I think many green groups continue to see environmental justice issues as sort of a lesser set of environmental issues as opposed to issues of paramount and singular importance to our nation, to our world. And that sort of marginalization of those issues and the communities for whom those issues are incredibly important continues to happen.

But what I see different at Earthjustice, and to give a fuller picture of Earthjustice’s entry into these issues … Earthjustice used to have an office in New Orleans for many years that just did some of the groundbreaking legal advocacy work around environmental justice in the nation. So Earthjustice had its own pipeline, as it were, into these issues to see what the issues were, to see how they played out and had some really gifted attorneys who led that office.

Earthjustice’s New Orleans office represented community members in a successful battle to block a polluting uranium plant. Residents Toney Johnson (L), Willie Brooks. (Daniel Lincoln)

People who worked in that office in New Orleans just brought all of that thinking, all of that understanding, all of that excellent, excellent, unparalleled legal advocacy to Earthjustice as an organization. And so there was already a foundation of understanding, a set of relationships, that had been established. And so, I’d say over the last four or five years, Earthjustice has also been making environmental justice central to a lot of its legal advocacy, so work around the coal combustion residual rule, work around the definition of solid waste rule, work around the mercury air toxics rule, and just a number of critical environmental policy issues that are on the table for us as a society today.

Earthjustice has decided that its vantage point into those issues would be principally drawn around environmental justice and who was being disproportionately impacted by these issues. So at a policy level, Earthjustice has made a real commitment to continuing that work that began out of its New Orleans office.

And so at a policy level, I think Earthjustice has made just an extraordinary commitment to continue to advance these issues, whereas many other environmental organizations have not made that commitment. But where we still lag behind substantially is the complete and utter lack of diversity among the staffs and the boards and even the donor bases of the environmental movement and environmental organizations in the United States. It’s still a really segregated place where a lot of people of color are not present within the workforces or the boards of directors of the environmental organizations.

At a policy level, I think Earthjustice has made an extraordinary commitment to continue to advance environmental justice issues.

And, as you said, I have worked on this for a really long time. Sometimes I have more sort of emotional energy to work on this, and sometimes I’m just so frustrated because we keep having the same conversations over and over and over. But we don’t do anything to systemically make our organizations look different and be different. And I think until you get more diverse voices within the mainstream environmental organizations, they will continue to see environmental justice issues as marginal, as sort of, you know, “We have to deal with the big systemic issues over here, and then we’ll get down to those little issues.” Well, they’re not little issues when your communities are dying disproportionately from environmental impacts. That is not a marginal issue.

How many environmental groups do you hear talking about the fact that there are still millions of people in this country who don’t have access to potable drinking water and sanitary sewage systems? Now, we see lots of conversation about trying to address these issues globally, in other countries, but we tend to act like those issues do not exist here in the United States and they do.

Communities of color, low income, tribal communities are disproportionately impacted by pollution. Above, Reid Gardner Power Plant towers over the Moapa River Reservation.

Climate change is yet another issue where there’s one perspective from communities of color and low-income and tribal communities who are already on the cusp of living in the places that are most directly impacted today, right now, by climate change. But yet when we see what the national conversation is in the environmental community about the policy prescriptions that they put forward to address climate change, they almost ignore entirely those dimensions of the issue that disproportionately impact environmental justice communities. So we’ve got a lot of work to do.

I think that the environmentalists have to exert as much energy and make this as much of a priority as people of color have done over the last 25 years. And until that happens, it’s just going to be a conversation. But we need substantive change and we need the change not just because it’s the right thing to do, but politically if we want to prevail in the political arena around these issues that we all know are so fundamentally important, than we need to have everyone who cares about these issues in a common conversation and working together to advance our objectives. The fractured nature of the environmental movement and the environmental justice community I think has continued to work to undermine our political effectiveness.

If you look at pure polling data, if you look at the group in Congress that has the most successful pro-environmental voting record, it’s the Congressional Black Caucus by orders of magnitude. They are a dependable environmental vote in Congress. When you look at statewide environmental initiatives, communities of color and low-income communities overwhelming vote for the pro-environmental record, and they tend to drive what happens in terms of environmental policy at the state and local level.

How many environmental groups do you hear talking about the fact that there are still millions of people in this country who don’t have access to potable drinking water and sanitary sewage systems?

But yet when you get into the conversation about setting the environmental policy direction, those constituencies are nowhere to be found or in marginal tokenized voices. And, I have never wanted to be a token and have never allowed myself to be a token. And most people of color, most women, feel that way. I want to be a part of the community. I want to help set the agenda. I want to help drive the agenda. I want to help implement the agenda. But I don’t want to be relating to that conversation in a marginalized way.

So we expect a more diverse Congress. We expect it from our administration. Right now there’s a big national conversation going on about how the president’s inner circle and his cabinet are not very diverse. We expect that now. That’s the baseline. And if we expect it from the President of the United States, then we certainly expect it from the environmental movement in this country.

Jessica: And you’ve mentioned that green groups have spent a lot of time talking about the issue and acknowledging the issue. What are some concrete steps you feel they should take to change the image of the environmental movement, which is predominantly white and focused primarily on conservation issues?

Vernice: It’s time for a deeper conversation. And I think the civil rights movement, the environmental movement, the women’s movement, that we have been on a trajectory that we set 20, 30, 40 years ago. And we have accomplished a lot of those things that we set out to do over the last 40 or so years in each of those movements. But we are well into a new century, and I think we need to revisit a lot of the fundamental issues that we are working on. We’ve accomplished a lot. But there are some new issues that have come up and that require our attention. And that we need to have these conversations and set a revitalized agenda, I think, for what we are going to spend our time doing, what we’re going to work on, what are our priority issues, where are we going to invest our resources. We need a new conversation about that. And we need to be in dialogue with each other.

The fractured nature of the environmental movement and the environmental justice community has continued to undermine our political effectiveness.

The civil rights community and the environmental community do not have a lot of overlap, but we need to have a lot more overlap and integration than we have had. And I think by talking to more diverse audiences, we will find that there are some issues out there that maybe have been under the radar screen that require more attention like lead poisoning, for example.

Why is that it’s still such a big issue in communities of color and tribal communities and in low-income communities. Lead poisoning is still a prevalent, public health threat that has long-term, irreversible life impacts for people who experience lead poisoning. Why isn’t this a bigger issue within the environmental community? Why? Why are we not focused with every ounce of our energy to making sure that we eradicate this scourge from every community that we can in the United States? And, of course it has global dimensions as well. Why is that not a front burner environmental issue for the community as a whole?

Jessica: A lot of the concerns of the environmental justice community, their focus on corporate accountability and unfair treatment of lower income people, it strikes me that it relates somewhat to the Occupy movement. Has the environmental justice movement been at all involved with Occupy?

Vernice: They have been separate movements so far. And I have just tremendous respect for how they stepped up, the way that they organically came together, the issues that they prioritized. But again, a social movement, where while there were some people of color in it, overwhelmingly not a lot of voices of people of color in terms of who’s being impacted by unemployment and lack of access to financial resources and so many of the other issues that Occupy took up.

Volunteers from Occupy Sandy take out drywall damaged by Hurricane Sandy in Rockaway, NY. (Elissa Jun / FEMA)

However, I think Occupy Sandy, the response from the Occupy movement to Hurricane Sandy and the after effects of Hurricane Sandy, has really been an extraordinary development of the Occupy movement. Occupy Sandy may begin to open up a level of integration of those two conversations that we hadn’t seen heretofore.

Jessica: And do you feel like grassroots advocacy is the best way to solve environmental justice issues? Has that been your experience?

Vernice: I think it’s a combination of many things. At the core has got to be strong, sustained grassroots advocacy and led by those people who are principally impacted by those environmental and public health threats. But I think in order for the efforts to be successful, you have to function at multiple levels. You need work by partner and sister organizations, legal advocacy organizations, research organizations, public health advocacy organizations to provide data and analysis on which those grassroots campaigns and efforts are based. You need an open dialogue between the folks who own and operate the facilities that are the sources of most of the pollution in these communities. You need an open conversation going back and forth about how to reduce the burden of pollution in those communities. And you need an ongoing conversation with the regulating community, with EPA, with state environmental agencies, with local and tribal environmental agencies.

You have to work it at multiple levels because the issues are so complex. It’s hard to keep all of those balls in the air at once, but that’s what you have to do. The further challenge is that most of these groups working on environmental justice issues are so vastly under-resourced. They get a pittance of the amount of philanthropic dollars that go to support environmental issues. So the fact that this constituency has achieved and accomplished what it has over the last 25 years, given the vast inequality in the amount of resources invested into that work and into the communities, is miraculous.

So, it’s been people power. It’s been moral persuasion. It’s been the articulation and passion of folk who come out of the civil rights movements of varying stripes. It’s been their perseverance that has kept this conversation moving forward for 25 years. But they’ve been moving on a track virtually by themselves.

And I think it’s time that we invest in those efforts, that the foundation community invest in those issues, that the faith-based community continue to support those efforts of the environmental justice movement and the civil rights movement get behind those communities and work with them to advance those objectives. I think we can make a lot more progress if we were all working together and not working in the fractured way that we have been working heretofore.

Jessica: So I know this is something that Earthjustice struggles with, and I’m sure other environmental groups do as well, how do you make people care about the environment, especially people who don’t easily identify with traditional environmental values like conservation?

Vernice: So now you’re talking about cultural differences, right? And people of color have always cared about environmental issues, always. You have the millennia of leadership and stewardship for environmental protection, conservation and sustainability of tribal communities. You have that of Asian communities, of Latino communities who have been agrarian for a large part of their existence here in this country who have worked to develop ancient systems of water conservation. You have African American communities who have sustainably managed forests in the southeastern United States.

A resident of California’s Central Valley, an area notorious for its particulate matter pollution. (Earthjustice)

Our ethos about conservation of natural resources goes way, way, way back. And, there has been somewhat of a dislocation as people have moved into urban environments and been more disconnected from the natural environment. And trying to keep those cultural connections is a challenge that we all face, but the notion that people of color and low-income folk, tribal communities, immigrant communities are less conservation-minded than are others is just pure hogwash. And there’s no scientific basis for it. There’s no analytical basis for it. It’s just something that people have in their heads, but it’s not true. And it’s never been.

But the language that we use to talk about these issues is something that has created barriers between folks. Conservation is a nice word and means a lot of things, but it’s a fairly high level conversation. But if you talk to the average person in any of these EJ [environmental justice] communities about what it means to protect their communities and their families, people will talk their heads off about what these issues mean to them and how they value these issues as part of the core of their existence.

So, I think we need to work on language. Environmentalists, it’s like we’ve developed a language onto ourselves, right, and we usually are talking to each other. And we’re comfortable talking to each other, but the more we talk to each other the more insular that conversation becomes, the more disconnected we become from the broader society who we are trying to engage in this conversation and trying to engage them politically in this conversation as well. And so I think we bear a tremendous amount of responsibility for the way that we have allowed the conversation about environment and natural resource management and conservation to evolve to a point where there’s only a select group of folk who really are engaged in that conversation. And we bear the responsibility for that.

And I think as a community we need to sort of go back to square one and think about how we are talking about these issues. And everybody’s working on this now, right? How to be persuasive and how to get your voting bloc and how to expand your voting base, etc. It’s not as complex as we make it out to be. But talking in a manner that is inviting, that is open, that is receptive to a broader cross-section of people is something I think we need to spend a tremendous amount of energy and time on doing because we’ve gotten really far off that path. And that’s really, really important that people understand what you’re talking about, but they also understand that what you’re talking about is fundamentally important to them.

And I think we have really moved away from that space, maybe we were never in that space given how the conversation around conservation began to grow in our society. It was a conversation that was related to wealth and access and those who had leisure time, and those who had time that they could spend hiking and doing watercolors of the landscapes, etc. That’s one way to approach the issues. And then there’s the rest of us who are living in the milieu, as it were, right. So we are living without access to safe and clean drinking water. We are living in spaces where we are not able to grow the food that you need to provide for your family and community safely without being exposed to chemicals and pesticides. There are people who are experiencing these issues in a profoundly different way than are others. And if you want to have a more dynamic conversation, if you want to have a more dynamic community of people who care about and work on these issues, the way we talk about them has got to change.

Jessica: I think that’s especially true when talking about climate change. Environmental groups have just not figured out how to talk about climate change in a way that relates to a majority of the public.

Vernice: Not only not talk about it, but also formulate the critical dimensions of the issues and what are the policy objectives that we’re going after in a way that speaks to a broader cross-section of people. So as with everything else in the environmental community, there is the environmental movement’s conversation about climate and then there’s the environmental justice movement’s conversation about climate, which is around climate justice. And those are also two parallel conversations that are passing each other like ships in the night. And there are some really big policy differences between those two conversations. And again, if we want to be successful, if we want to be effective, we need to be having a different kind of conversation. We need to be open to different dimensions of the issues.

Close Video

Video:

Asthma Feels

Millions of Americans suffer from asthma. However, most people don’t know how brutal it is to live with the disease.

Breathing is a fundamental right, yet everyday air pollution is affecting millions of Americans’

right to breathe.

Our lungs don’t need to be the dumping ground for dirty industries.

Learn more: The Right to Breathe

One of the issues that EJ communities are really focused on are the emissions that are not necessarily carbon emissions, but other localized emissions that come from those same sources of greenhouse gases that affect local communities. These are the things that are triggering asthma, that are triggering asthma mortality, that are happening at epidemic rates in EJ communities.

Those issues are a dimension of greenhouse gas emissions, but they are being talked about by the climate justice and environmental justice advocates, but not necessarily by the environmental community. That has got to change. The sooner that we can integrate those conversations, I think the more effective we’ll be in the political arena.

Jessica: Over the years, you have had so many environmental battles, yet there are so many environmental challenges that still face humanity. How do you avoid not getting bogged down by the direness of the environmental issues that we face?

Vernice: Wow. What a really good soul-searching question. [laughter] How do you not get bogged down or depressed? Well, every little victory a life is saved. Every big victory is a major advance for our society and for our planet. So I guess I am the eternal optimist. I know that what we’re working on is to try and preserve not just this planet that we live on, but the people who live on this planet. And I’m working really hard and I’ve seen a lot of victories, a lot of challenges. Our community in West Harlem, for example, no longer has the highest premature death rate from asthma. So we’ve made progress in our own community in New York.

As long as folks from local communities still have the energy to move this agenda, then I still have the energy to support them in every way that I can.

We are seeing the overall number of children who are showing or demonstrating elevated levels of blood lead, those numbers are going down, though any number is still too high. We are seeing an improvement in water quality, a dramatic improvement in air quality. But there are still challenges. And so, you’ve got to keep working until you reach a point of sort of environmental stasis where things are as they should be and there’s a long way to go towards that. But if I look back, we have progressed so much in terms of where things were as opposed to where they are today. But the progress has been brought about by a lot of work, a lot of legal advocacy, a lot of policy advocacy and most importantly, a lot of grassroots activism to show that these issues are really important to local communities.

And so, as long as folks from local communities still have the energy to move this agenda, then I still have the energy to support them in every way that I can. And it is a really good feeling. I’ll say this, enormously challenging though the issues are, it’s a really good feeling going to sleep and wake up every day knowing that you are spending your time in a productive pursuit of justice and equality.

And that is probably what sustains me, that I know that my efforts are being spent to make life better for lots and lots of people who right now are suffering. But the more effective and the more strategic we are, the more successful we are, the more benefits we bring to more people, more communities, more of our natural resources are protected. That is what sustains me, that this is a pursuit for justice and that is something that I go to bed and wake up every day feeling really good about how I spend my time.

Jessica: Definitely. Is there anything else that you’d like to add?

Enormously challenging though the issues are, it’s a really good feeling going to sleep and wake up every day knowing that you are spending your time in a productive pursuit of justice and equality.

Vernice: Just that I’m really proud of Earthjustice and the work that they continue to do. I have lots and lots of colleagues at Earthjustice who are doing extraordinary work. I should say that tomorrow many of us will be together celebrating the life of [Earthjustice’s Senior Legislative Counsel] Joan Mulhern, an extraordinary champion for environmental justice and environmental protection who passed away recently at a much too young age. But we will gather to celebrate Joan’s life and her work and know that we’re sort of all asking ourselves, when faced with difficult challenges, what would Joan do? And the answer is, Joan would say, “Fight like hell.” And that’s what we will continue to do.

Jessica: Vernice, thank you again for your time. It’s really been a pleasure.

Vernice: You’re so welcome.

Jessica: Vernice Miller-Travis is the Vice Chair of the Maryland State Commission on Environmental Justice and Sustainable Communities and co-founder of WE ACT for Environmental Justice. In 2011, she participated in Earthjustice’s 50 States United for Healthy Air campaign. For more information about Earthjustice’s clean air work, check out earthjustice.org/r2b. And to hear more Down to Earth interviews with environmental experts, please go to earthjustice.org/d2e.

Related:

Interactive Feature

50 States United for Healthy Air

Clean air should be a fundamental right. Every year, many young and old get sick because of air pollution. Thousands die. But our bodies don’t have to be the dumping ground for dirty industries. Clean Air Ambassadors traveled to Washington, D.C. to defend our right to breathe.

Magazine Feature

Recycling’s Dark Side

Recycling is a great idea—unless you live next to a site pouring toxins into your neighborhood. Across America, it’s a matter of environmental justice.

Podcast

Down to Earth, an Earthjustice Podcast

Down to Earth is an audio podcast about the news, events and personalities that make up Earthjustice. Hear from attorneys, clients, scientific experts, and more on Earthjustice litigation.

#page-title { color:#000; font-weight:normal; font-family:’palatino linotype’,georgia,serif; font-size:44px; top:15px; }

#breadcrumb { top:-55px; position:relative; }

.title { top:0px; position:relative; padding-bottom:6px; }

.feature-right-column { position:relative; z-index:15; }

#node-pic p { line-height:13px; padding-top:2px; }

#node-pic { margin-top:0px; }

#content #d2e-transcript p { color:#000; font-size:13px; }

#content #d2e-transcript a { font-weight:normal; font-size:13px; }

.pullquote { font-family:georgia,serif; font-size:15px; line-height:21px; color:#000; float:left; width:250px; margin:5px 0 5px 20px; padding:2px 35px 5px 20px; background-image: url(‘http://earthjustice.org/sites/default/files/feature_full/2010/quote_open…</a>'); background-position: left top; background-repeat: no-repeat; }

.pullquote-end { display: block; background-image: url(‘http://earthjustice.org/sites/default/files/feature_full/2010/quote_clos…</a>'); background-position: right bottom; background-repeat: no-repeat; }

.overlay-close { width:920px; height:27px; clear:both; position:relative; z-index:50; }

.overlay-close-img { float:right; cursor:pointer; padding:6px 0 0 0; }

.overlay-close-text { color:#fff; text-transform:uppercase; font-size:9px; letter-spacing:1px; font-family:arial,sans-serif; padding:10px 8px 0 0; float:right; cursor:pointer; }

#content #d2e-transcript .item-video-play p.trailer-text { display:block; color:#ccc; font-size:12px; font-family:arial,sans-serif; line-height:14px; padding:10px 0 8px 0 0; }

document.getElementById(“sh-title”).innerHTML = “Podcast: Down To Earth”;

document.getElementById(“page-title”).innerHTML = “Ecology Without Equality”;

$(‘.item-caption’).click( function() {

($(this).height() < 52) ? $(this).stop().animate({height:'52px'},{queue:false,duration:160}) : $(this).stop().animate({height:'10px'},{queue:false,duration:160});

});

$(‘.item-video-off’).click( function () {

$(this).fadeToggle(“fast”, “linear”, function () {

$(‘.item-video-play’).clone(true).appendTo( $(‘.item-video-container’) );

$(‘.container-video’).append(”);

$(‘.item-video-container > .item-video-play’).fadeToggle(“fast”, “linear”);

});

});

$(‘.overlay-close’).click( function () {

$(‘.item-video-container > .item-video-play’).fadeToggle(“fast”, “linear”, function () {

$(‘.container-video’).empty();

$(‘.item-video-container’).empty();

$(‘.item-video-off’).fadeToggle(“fast”, “linear”);

});

});