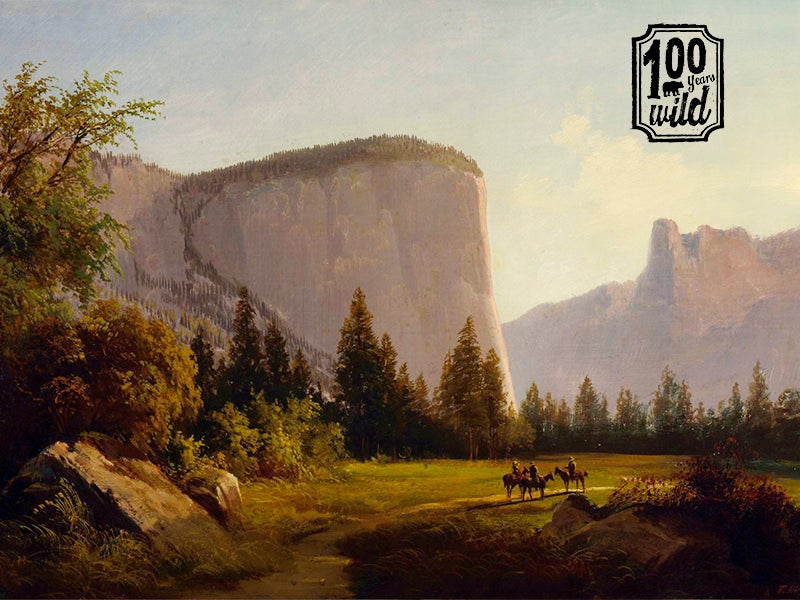

The National Parks Through an Artist’s Eyes

Art has long played a defining role in generating public support for the National Park Service.

This page was published 9 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

“No place is a place until it has had a poet.” – Wallace Stegner

Art has long played a defining role in generating public support for the National Park Service. Early 19th-century painters like James Audubon elevated nature artwork in the public eye and sowed the seeds of conservationism. Paintings of Yosemite from artists like Thomas Hill moved President Lincoln, in 1864, to protect the valley as a park. Ansel Adams succeeded in getting a copy of his limited-edition book “Sierra Nevada: the John Muir Trail” to Franklin D. Roosevelt, which helped inspire the creation of Kings Canyon National Park.

More recently, renowned pianist and composer Ludovico Einaudi brought the plight of the Arctic to the attention of hundreds of thousands of people with a haunting performance among the icebergs of the region. Activist Van Jones and artist Favianna Rodriguez have also teamed up to put artists from diverse backgrounds, who are often the most impacted by global warming, at the forefront of the climate battle.

Last May, the David Brower Center in Berkeley, California, kicked off the National Park Service’s 100th birthday on August 25 with an exhibit that showcases the work of 20 local artists who have found inspiration and meaning in our parklands. The exhibit, “Common Ground: A Celebration of Our National Parks,” honors the legacy of David Brower, an environmentalist and mountaineer who led campaigns to establish 10 new national parks and seashores, including Point Reyes National Seashore, North Cascades National Park and Redwood National Park. Brower was also fiercely proud of his artistic abilities, including photography, painting, writing and filmmaking.

As many national parks face the threat of encroaching development, the role of art in celebrating and publicizing the beauty of the parks remains essential. We spoke with Kimberley D’Adamo Green, an Oakland-based painter, about her contribution to the Brower Center exhibit and her relationship with the national parks. The painting D’Adamo lent to the exhibit, called “Emotional Interior of Biology No. 36,” was inspired by her recent residency at the Lucid Art Foundation in Inverness, California, where she spent three weeks studying Point Reyes National Seashore.

Anna Guth: What drew you to the national parks as a source of inspiration?

Kimberley D’Adamo Green: Years ago, I started focusing my work on California coastal ecosystems. At the time I was living in East Oakland in a metal warehouse bounded by three train tracks. It was overwhelmingly industrial, loud and dry. To escape the sea of concrete, I started exploring the landscapes off Route 1 and discovered the parks: Big Sur, the Marin Headlands and Point Reyes. These natural spaces are a remarkable contrast to our built world, and places where water shapes the landscape in a more direct, chaotic and beautiful way. I wanted to document both my observations and my emotional relationship to those landscapes as a way of celebrating what we had had the foresight to preserve.

AG: Your art piece combines different perspectives. How do you want to encourage your viewers to see nature?

KD: I love the machinery of science and the new ways of viewing the world around us. These optical technologies—microscopes, satellite imagery and drone video—have shifted our understanding of scale and space, our relationship to the natural world and our awareness of the damage we are doing. They have allowed us to see and feel in a new way.

For my work, I explore three types of documentation: satellite images of the area I am painting, photographs I take on my walks in that area and images from my digital microscope of specimens I collect. I try to juxtapose and layer these images and paint them in such a way that my emotional connection to the landscape is revealed. My process speaks about a shift in the way we interact with the earth and a concurrent questioning of our place in nature. I want people to feel the connection we all have to nature.

AG: What do the national parks still have to teach environmentalists, nature-lovers and artists?

KD: We are one part of a larger system, and we are both physically and emotionally dependent on that system to remain healthy. Our awareness of that often fades away when we live our urban lives. The parks provide a refuge in a world that is increasingly mechanized and self-centered. They are a place where you can feel connected to the enormity of our landscape and find yourself lost in the grandness of creation.

(Until September 8, you can find D’Adamo and her fellow artists’ work on display at the David Brower Center in Berkeley.)

As the National Park Service turns 100 this summer, the 100 Years Wild series celebrates the value of public lands as refuges to wildlife and people, while also shining a light on the threats to these irreplaceable landscapes in a changing and warming world.