Hawai‘i’s Aquarium Pet Trade Was a Deadly Business.

We Put a Stop to It.

April 20, 2022

Rene Umberger never expected a legal fight over the aquarium pet trade to put her life in danger.

It was 2014, and Umberger was scuba diving in Hawaiʻi to document the ecological destruction that occurs when commercial divers scoop up wild fish in the ocean to sell for at-home aquariums. While diving near the Kona coast, Umberger spotted two divers collecting fish from a nearby reef and began filming them. Before she could react, one of the divers charged Umberger and ripped the breathing device out of her mouth. For the inexperienced, the move could have been fatal. But Umberger, a dive instructor with more than 10,000 dives, was able to quickly replace her gear and safely surface.

The underwater assault underscores a longstanding battle between aquarium collectors and those who oppose the trade. But dive a little deeper, and the conflict goes beyond individual actors and one-off skirmishes. Hawaiʻi’s state regulators, by failing to protect a public resource, are the main culprits stirring the waters.

Commercial aquarium collection in Hawaiʻi harms local communities and ecosystems, just as other unrestrained industries like logging, mining, and fossil fuel drilling around the country harm Native and nearby communities. The climate crisis, coupled with the biodiversity crisis, only worsen the situation. Scientists say we must push for urgent, transformative change to address these multiple planetary stressors — or risk life as we know it.

In Hawaiʻi, Earthjustice is using state laws to protect public resources like wild fish and the reefs they rely on from the multibillion-dollar aquarium industry. With each win, we’re defining what it means to truly protect public resources in the face of multiple crises.

A Deadly Process

Fewer than 1% of wild-caught fish survive beyond a year.

Stare for a minute at any saltwater aquarium and you’ll likely find yourself transfixed by the kaleidoscope of creatures swimming among faux corals. The soft bubbling of the filtration system might even lull you to sleep.

But behind this tranquil scene lies a brutal and often deadly reef-to-retail process.

In Hawaiʻi, which for decades was a major supplier of the world's aquarium pet trade, until recent court victories prohibited the practice, fish were often captured and pierced with hypodermic needles to release air and mitigate injury from the fish version of “the bends.” Once in a warehouse, fish were starved for up to 10 days so they wouldn’t foul the water inside the small plastic bags they were eventually placed in. Then, fish were transported thousands of miles to another warehouse, where the same pattern was repeated.

According to the late Bob Fenner, a marine aquarium expert, fewer than 1% of wild-caught fish survive beyond a year, and many die before they get to the pet store. In comparison, saltwater fish species can live for decades in the wild.

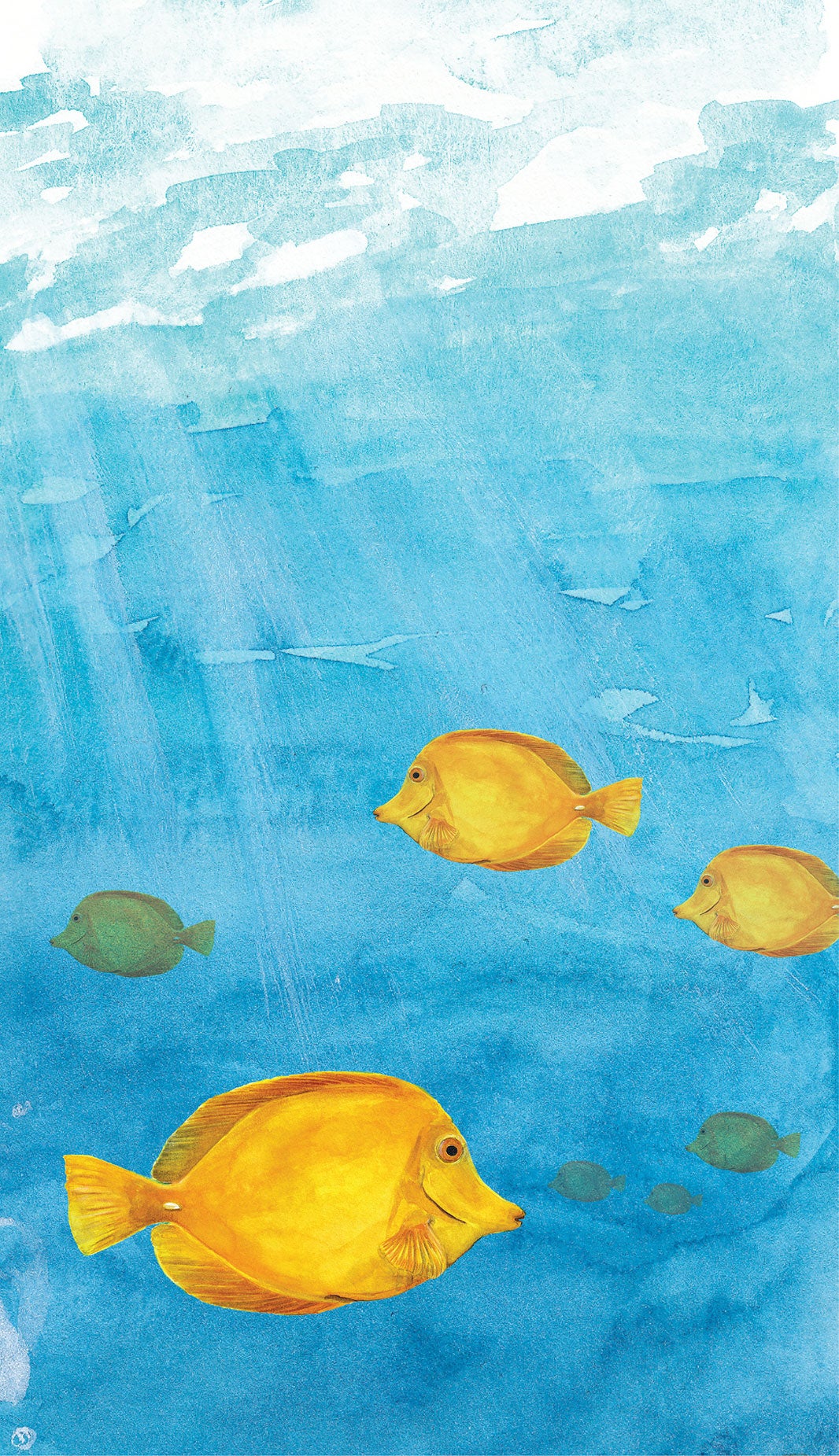

“These are wildlife, and yet they’re treated so poorly,” says Umberger. “Fish like the yellow tang can live longer than your dog or your cat, but in captivity they’re dying within weeks and months.”

Hawaiʻi’s native fish, many of which are unique to the islands, serve longstanding cultural values. Native Hawaiians often catch fish like the pākuʻikuʻi (Achilles tang), a tropical surgeonfish with a striking bluish black body and orange accents, to feed their families. Before European contact, native fish were also used in religious and medicinal ceremonies — practices that continue today.

In addition, reef fish provide critical ecological services by eating algae off the reefs, which allows coral to breathe and access sunlight. The reefs, in turn, serve as buffers against ocean waves, storms, and floods, which are worsening with climate change. Known as “rainforests of the sea,” reefs are also key biodiversity hot spots, with about 25% of the ocean’s fish dependent on them. The Northwest Hawaiian Island coral reefs, for example, support more than 7,000 species, including fish, invertebrates, sea turtles, birds, and marine mammals as part of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

Yet for 50 bucks a year, Hawaiʻi residents could get a permit to take as many reef fish out of Hawaiʻi’s waters as they’d like, with rare exceptions. Between 1976 and 2018, the aquarium pet industry took more than 8.6 million fish from West Hawaiʻi waters for use in aquariums around the world.

After years of watching the reefs deteriorate into “deserts” and the state ignore the problem, Umberger came to Earthjustice for help.

A Legal Hook For Change

Under the Hawaiʻi Environmental Policy Act (HEPA), the state must scrutinize a proposed project’s environmental, cultural, and socioeconomic impacts before approving it. One day, Umberger came across a document describing the state’s attempt to exempt the aquarium collection industry from HEPA entirely.

A lightbulb went on.

“I suddenly realized that HEPA was a real avenue where we could effect change,” she says.

Soon after, Earthjustice sued the state for failing to use its power under HEPA to regulate the aquarium industry. Around the country, Earthjustice has been fighting — and winning — similar battles, where poor regulation of extractive industries imperils ecosystems and species already stressed out by climate change. As the biodiversity crisis worsens, with scientists estimating that more than one-third of all species may face extinction by 2050, Earthjustice is also fighting to protect key ecological zones like coral reefs around the world.

Throughout the initial legal battle in Hawaiʻi, the state refused to acknowledge the aquarium pet trade’s impacts or even its duty to study them.

“All of these lawsuits are, in essence, about preventing the agency from recklessly handing out permits,” says Earthjustice attorney Mahesh Cleveland. “The people who are given the privilege and responsibility to take care of our public resources must know exactly what’s going on with those resources before they allow extractive practices to proceed.”

To illustrate the industry’s impacts on communities to state regulators, Earthjustice brought in clients like Willie and Ka’imi Kaupiko, a father-son duo from Miloliʻi. A small, isolated community on the west side of the Big Island, Miloliʻi is one of Hawaiʻi’s last traditional fishing villages in a state where these villages historically abounded.

“When I go fishing, I hardly see any of the types of fish collected by the aquarium trade out on the reefs anymore,” says Ka’imi. “We live off this resource, we understand it, and we have a deep relationship to it. But these guys [the commercial aquarium collectors] will do whatever it takes to gather as much as they can, and they give nothing back to the community.”

Earthjustice’s case eventually made it to the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court, which ruled in 2017 that regulators can’t ignore the devastating impacts of unlimited commercial fish collection on Hawaiʻi’s reefs. The court also determined that regulators can’t allow more commercial collection until they adequately study the industry’s environmental impacts.

The legal win was huge, but the state continued to help the industry. Regulators even created a loophole for the industry to keep collecting without environmental review. With each attempt, Earthjustice attorneys hauled the state back to court.

In 2020, the ground finally started to shift. After years of legal defeats, a governor-appointed board historically prone to rubberstamping the trade determined that the environmental assessment of the trade’s impacts in West Hawaiʻi was inadequate. And in 2021, the board voted to reject the environmental assessment for the aquarium pet trade on Oʻahu, another collection hot spot. In rejecting the assessment, the board went against its staff’s recommendation and echoed many of the flaws that Earthjustice and its clients had identified during testimony.

“Our environmental laws are all about going to the public, and yet the regulators didn’t even call community leaders that would be most affected by the proposed activity,” says Earthjustice attorney Kylie Wager Cruz. “I think that was huge for some of the board members.”

A Deadly Process

For the first time in generations, there is currently no legal commercial aquarium collection around the islands. Hawaiʻi’s reefs are finally getting a reprieve — and a chance for renewal.

After the court curtailed aquarium collection in West Hawaiʻi, scientists saw the largest annual increase of lauʻipala (yellow tang) ever recorded in 2018. As climate change induces coral bleaching in Hawaiʻi and around the world, resurging reef fish populations could provide a life raft for ailing coral by eating algae and promoting coral recovery.

Less qualitative but equally tangible is the renewed sense of tranquility found in areas where aquarium collection has been banned.

“Fish are eating my air bubbles once again,” says lifelong scuba diver Mike Nakachi, who explains that naturally curious fish like the kīkākapu (Tinker’s butterflyfish) will interact with you in the water — if they haven’t been previously harmed or harassed by collectors.

Nakachi and Kaupiko, both Native Hawaiians, want to see a Hawaiʻi where the land is restored, and the communities with it.

“Our vision is to be a thriving Hawaiian fishing community,” says Kaupiko, who teaches traditional and responsible fishing practices to children in West Hawaiʻi. “Giving the children a foundation and understanding of Hawaiian values helps them succeed whether they decide to stay here or not.”

“Anything done on an industrial level should really be under the microscope...”

Kaupiko is also helping to create a marine management plan to strengthen protections of key subsistence species and increase self-sufficiency. And Nakachi, who is also part of an Earthjustice lawsuit to protect whitetip sharks from industrial fishing, wants to see the cultural considerations in the aquarium lawsuits extend to other potentially harmful activities.

“Anything done on an industrial level should really be under the microscope, especially in this day and age,” says Nakachi. “We have only these eight beautiful islands in the middle of the Pacific, and they can only sustain so much human impact.”

Despite the current ecological crises, Nakachi remains hopeful about the future. He’s seen how Earthjustice litigation has forced a shift among legislators and regulators in recognizing cultural values and respecting a sense of place, particularly in a climate-changed world. And he sees how Earthjustice attorneys have successfully pushed for changes within the law that reflect the hearts of the people.

“Having culture, having that identity of place, it’s no longer seen as a bad thing,” says Nakachi. “Hawaiians aren’t Hawaiians without ʻĀina, [which means ‘land’], and ʻĀina isn’t the same without Hawaiians.”

Established in 1988, Earthjustice's Mid-Pacific Office, located in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, works on a broad range of environmental and community health issues, including to ensure water is a public trust and to achieve a cleaner energy future.

Mahesh Cleveland is a senior associate attorney based in Honolulu. Kylie Wager Cruz is a senior attorney, also based in Honolulu. Jessica A. Knoblauch is a senior staff writer at Earthjustice. Ceylan Sahin Eker is a watercolor illustrator based in Brooklyn, NY.