Justice for the Earth and Its People

The exploration of landmark cases behind Earthjustice's rise and reinvention.

Justice for the Earthand Its People

The exploration of landmark cases behind Earthjustice's rise and reinvention.

With the growing visibility of environmental issues in our daily lives, it’s surprising to consider how new environmental law is.

Earthjustice has been involved from the beginning. Launched in 1971 as the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, our founding litigators were admirers of the Earth who found cause in its defense and opportunity in the American court system.

The organization’s earliest lawsuits were filed in a void of infrastructure for environmental claims. But as city skies filled with gray, polluted rivers burst aflame, and people’s vitality succumbed to their chemical environments, a wave of activism that grew through the 1960s delivered what we needed. A burst of federal laws were passed, including the National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act, that gave Earthjustice legal grounds to stand and grow upon.

“From the start, Earthjustice has enforced the environmental laws of the 1970s with extraordinary impact, and that will always be core to who we are,” says Earthjustice president Abigail Dillen. “Over time, we have come to understand the role that environmental health plays in human health, the throughline between social justice and environmental justice, and the existential threats of climate change and biodiversity collapse.”

The historical vignettes that follow offer glimpses into Earthjustice’s first 50 years. We revisit landmark victories — and prolonged pursuits — that took us from an inceptive focus on place-based litigation to a full-scope legal strategy that addresses public health, environmental racism, and the very habitability of our planet.

Our evolution is shaped by the constant exercise of living out our core values and working in partnership with clients whose pursuits of justice illuminate our own journey.

Saving Public Lands

Lawyers With a

Love of the Wild

The first cases brought by Earthjustice nearly all involved public lands. The federal government owns and manages nearly a third of the total land area of the country. The case that led to the creation of Earthjustice involved a remote and fragile valley in the southern Sierra Nevada in California called Mineral King.

In the mid-1960s, the Forest Service, which managed Mineral King, approved a permit that would allow Walt Disney Enterprises to build a massive ski resort in the valley. The plan envisioned two dozen ski lifts, hotels, restaurants, a huge underground parking garage, and other buildings.

The Disney resort was never built, and a pathway for sustained defense of public lands was revealed.

The Sierra Club thought this was a dreadful idea that would ruin Mineral King for anglers, backpackers, birders, and wildlife. The group filed a lawsuit arguing that the ski resort would be illegal in at least three respects. The government responded that the club didn’t even qualify to bring its case to court since it wouldn’t be financially harmed by the project. The club replied that its members should have the right to protect their interests in recreation and other non-monetary concerns. Although the Supreme Court ruled against the club, the lawyers were eventually able to establish the principle that conservation interests deserve their day in court. The Disney resort was never built, and a pathway for sustained defense of public lands was revealed.

Earthjustice’s founding attorneys followed that path and, over the next decades, the growing organization brought hundreds, if not thousands, of cases seeking to prevent the excessive logging of national forests, stop harmful dams from being built, challenge coal and uranium mines, block oil and gas projects, oppose highway construction and other ill-advised schemes on federal lands, and protect and defend wilderness and sensitive ecosystems.

One long-lasting group of cases involved something called the Roadless Rule. Near the end of the Clinton administration, the Forest Service protected nearly 60 million acres of national forest from new road construction. It took this step because there were already hundreds of thousands of miles of roads in the national forests in disrepair. Roads lead to runoff into streams, new logging and extraction of all kinds, and habitat fragmentation. States and timber companies filed nine suits to block the rule. Earthjustice mounted a defense to each and every one. It was a protracted and messy affair, but, after 20 years, the rule continues to hold firm, protecting millions acres of forest.

Preserving Earth’s Biodiversity

Litigation for the Land

and the Living

In 1973, Congress passed, and President Nixon signed, the Endangered Species Act (ESA). This came in response to a dismal history that had seen hundreds of species of wildlife pushed to the brink of extinction by human activities. Earthjustice made enforcement of the ESA a major part of its docket starting in the late 1970s.

On the big island of Hawaiʻi lives a small bird called the palila, which lives nowhere else. Its numbers have been decimated by feral sheep and goats. The hoofed mammals eat seeds and shoots from the trees that provide the only source of food and shelter for the palila. Scientists had understood this problem for some time, but the state of Hawaiʻi argued that the ESA didn’t apply to the palila because the sheep and goats weren’t harming the birds directly. Earthjustice went to court and argued that destroying a protected species’ habitat is as damaging to the species as shooting or otherwise directly harming it. The court agreed, and Congress eventually made habitat protection explicitly required.

Destroying a protected species’ habitat is as damaging to the species as shooting or otherwise directly harming it.

This outcome allowed Earthjustice in the subsequent decades to confront head-on the biggest driver of extinction: the loss of habitat from resource extraction, development, and now climate change.

Nowhere was this more visible than the Pacific Northwest in the late 20th century. The timber industry tried to log the last of the region’s old-growth forests despite mounting local activism. Enter the northern spotted owl, which lives up in the tops of those giant trees. Its numbers were plummeting and yet the government refused to grant it protection under the ESA — until Earthjustice lawyers filed suit, bolstered by the palila ruling. The litigation forced a political solution that moved the region away from old-growth logging. Today, the owls and their forest habitat endure.

Litigation focused on habitat protection has helped forestall, for now, the demise of species including the Greater Yellowstone grizzly bear, wild salmon, gray wolves, the Canada lynx, and the California sea otter. But in the U.S. and worldwide, the plight of many species remains grave.

Preserving Earth’s Biodiversity

Leveraging the Law for

Healthier Human Habitat

The Colorado Plateau in the southwestern U.S. has some of the most spectacular sandstone scenery in the world. Not coincidentally it hosts a major concentration of national parks, recreation areas, forests, national monuments, and other protected areas. It has, or had, the cleanest air in the contiguous United States. It’s also the site of some 30 Native reservations. And, to complicate matters considerably, it has vast deposits of coal, oil, natural gas, and uranium.

In the 1960s, a multi-unit coal-fired electricity plant was built on Navajo land near the Four Corners, where Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona meet, and smoke from the plant was blanketing the plateau to the detriment of lungs and vistas. Seeing the impacts, conservation groups initiated a long-term campaign to shut down coal projects throughout the region.

In these endeavors, the groups, often represented by Earthjustice, would frequently make alliances with tribal leaders. While the conservationists continued to block projects that would unleash air and water pollution across the iconic landscape, the tribes were mounting resistance to mining on their land. There was a synergy in their interests, although the Native groups were no more monolithic than the conservationists, some of whom had supported coal plans to stave off more hydro dams in the region. And the litigation that ensued was complicated and protracted.

Over 100 of the nation’s most polluting coal plants have been taken offline as a direct result of Earthjustice litigation.

To mention just one matter, the states and utility companies pushing new coal power came up with a scheme to deal with the tons of pollutants that would be emitted daily by the plants: build the smokestacks nearly 800 feet tall. It was hoped that the nasty stuff would just disappear if released up that high. Some tall stacks were built to disperse smoke from coal plants in the Midwest; all they did was vault the pollution into the Northeast and Canada. (There are mechanical ways to remove the pollutants, but they cost more than smokestacks.)

Earthjustice lawyers went to court, over and over, and eventually defeated most of the tall stacks. Likewise with the mines.

The efforts to stop coal mines, power plants, and waste dumps were originally aimed at reducing air and water pollution and protecting viewsheds. Over time, this work expanded into cities and towns, areas where concentrated coal-based pollution is fueling public health crises, and it has become a fight to protect the climate itself.

Over 100 of the nation’s most polluting coal plants have been taken offline as a direct result of Earthjustice litigation. We secured the first federal regulations for dealing with the nation’s legacy of toxic coal ash and are committed to challenging coal projects at the state and federal levels until the industry is fully retired. Today, just as when we began, this work continues to draw people from all walks of life into powerful alliances.

Ending the Climate Crisis

The Battles to Break Free

from Fossil Fuels

As early as the 1950s, petroleum scientists were observing the environmental effects of burning fossil fuels. By the 1960s, researchers were warning the industry of certain and significant global warming by the year 2000 and predicting sea-level rise driven by Arctic melt. By the 1970s, the industry’s scientists were no longer speaking in hypotheticals.

What followed has been described by author and climate campaigner Bill McKibben as “the most consequential cover-up in U.S. history.” Industry giants like Exxon buried their researchers’ findings, then waged a decades-long disinformation campaign to keep the oil and profits flowing. Fossil fuels’ grip on our economy tightened. The entrenchment of the industry in politics created a toxic stew of deceit, denial, and deference to the status quo.

But facts still matter in court.

Earthjustice has been laying the groundwork for climate litigation, bridging law and science to establish precedents that force action and remove barriers to progress.

Although political solutions have, until recently, been slow to take root, environmental advocates have worked steadily for years building legal cases for climate action. In 2020, more than 1,500 climate cases were filed worldwide. In the U.S., Earthjustice has been laying the groundwork for climate litigation, bridging law and science to establish precedents that force action and remove barriers to progress.

Our landmark 1993 defense of the Clean Air Act in the U.S. Court of Appeals, argued by Earthjustice attorney Howard Fox, has been a basis for much of this progress. The court’s decision affirmed the government’s lawful duty to protect the public from harmful emissions released by gas-powered motor vehicles. At issue was whether the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) holds rulemaking authority, or simply a consultative role for the U.S. Congress, in the issuance of national safety standards under the Clean Air Act. The court’s decision cited “plain and unmistakable language” that it was the EPA’s duty to develop and enforce clean air standards.

In 2006, Earthjustice served as co-counsel in Massachusetts v. EPA, in which the Supreme Court affirmed that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are air pollutants under the Clean Air Act, and that the EPA must mitigate their contributions to climate change. This victory has since withstood repeated industry attempts to avoid responsibility for the harms caused by its products.

Today, Earthjustice is taking the fight to courts across the nation, ensuring decision-makers at all levels of government are prioritizing clean energy and electrification, and partnering with overseas organizations to promote these objectives abroad.

Confronting Environmental Racism

Building Power for a

Just and Equitable Future

At the time of Earthjustice’s founding, it wasn’t unusual to see front-page news of court battles over equal access for people of color to voting, jobs, education, and housing. The landmark civil rights laws of the 1950s and 1960s were achieved through sustained organizing by a diverse network of advocates that included lawyers, many of whom were involved with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

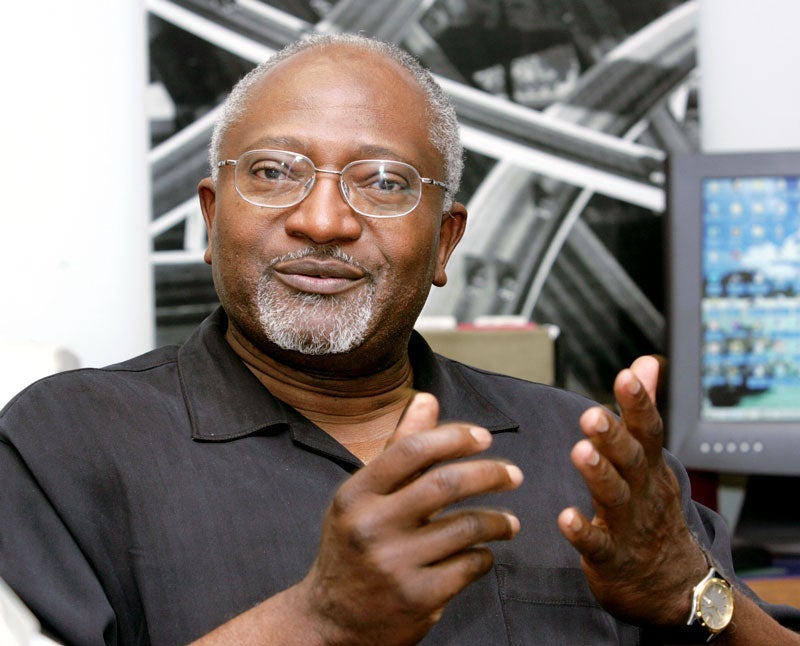

The litigation that gave momentum to the Civil Rights Movement created a platform for everyday people to challenge great injustices at the highest levels. And as the scope of conservation movements expanded from the American wild to also address threats to cities, towns, and the people within them, the interlocked crises of systemic racism and environmental destruction became impossible to ignore. Acclaimed justice advocate Dr. Robert Bullard has described this baneful combination, otherwise known as environmental racism, as “a form of illegal ‘exaction’ [that] forces disenfranchised communities to pay costs of environmental benefits for the public at large.”

This was the pronounced reality in a case that began in 1989 and concluded eight years later as one of the nation’s first victories for environmental justice. The case involved a proposed $850 million uranium enrichment plant that would have saddled two rural Black communities around Homer, Louisiana — Center Springs and Forest Grove — with radioactive waste built up over 30 years of operation.

The residents found crucial allies in some of the White people who lived in Homer who were concerned about the facility polluting local waters. Together, they formed a biracial coalition under the banner of Citizens Against Nuclear Trash (CANT). Nathalie Walker, the late founding attorney of Earthjustice’s New Orleans office, was tapped to serve as co-counsel in their challenge before the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board.

Dr. Bullard provided expert testimony in the case. He called the court’s attention to the community’s protection under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970. That law affords those who would be affected by a federal project the right to be informed and to voice concerns before any permits are approved. He also cited a 1994 law that was vital to CANT’s challenge: an executive order issued by President Clinton to identify and address the disproportionate health and environmental harms that federal projects were inflicting on people of color and low-income communities.

With a ruling that ratified environmental justice as a moral mandate, the facility’s license was denied and the project was scrapped in 1997. Since this decision, polluting industries have continued to flout the law and foist environmental burdens onto marginalized populations. Earthjustice, working with environmental justice partners, is challenging these threats where they cast the widest shadows.

“Earthjustice has never been stronger or more diverse. As we grow and branch into new areas to pursue solutions on an ever-greater scale, one thing will never change, and that’s our focus on harnessing the law to force the change we need.”

Abigail Dillen

President of Earthjustice

Maz Ali was the managing editor for Earthjustice from 2020 – 2021.