Dusky Sharks: Top Predators that Need Our Protection

Dusky sharks are top ocean predators—even hunting other sharks—but they’re no match for destructive longline fishing gear.

This page was published 8 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

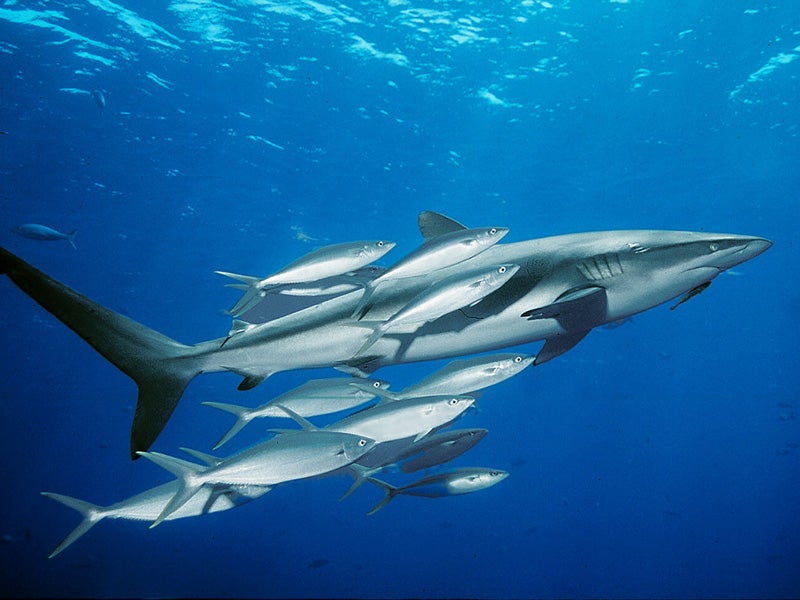

A toothy top predator roves across a wide plain hunting for prey. The beast is magnificently adapted to her surroundings—her sleek, grey shape nearly fades into the distant blue despite her impressive size. She will travel hundreds of miles this season following food and favorable temperatures, eventually finding a mate in the vast range of her travels. Many months later, she will deliver pups and, with them, a bit more hope for her species.

The predator is a dusky shark, one of the largest shark species to roam the U.S. Atlantic coast—and one of the most imperiled.

When you think of “shark,” the image that comes to mind probably looks a lot like a dusky shark – grey on top, white on bottom, more streamlined than the beefy great white, with a classic triangular dorsal fin and sweeping tail fin. Duskies are big. Adults average just less than 12 feet in length and weigh around 400 pounds. They’re big enough to eat other elasmobranchs, which means they eat skates, rays and even other sharks. That’s pretty badass. It’s also ecologically important. As apex predators, dusky sharks are crucial for maintaining balance throughout the ocean food web.

Despite their top spot on the food chain, there are only a handful of reports of dusky sharks attacking people. Sadly, we haven’t been nearly as selective in how gathering our human food affects the dusky shark.

Before U.S. fishermen were banned from landing dusky sharks in 2000, commercial fishermen hunted the species to satisfy demand for shark fin soup and shark liver oil. Recreational fishermen hunted them for the sport of wrestling a big predator that put up a strong fight. The dusky shark population plummeted by about 80 to 85 percent since the mid-1970s, with much of that decline between the late 1980s and 2009.

The 2000 ban on fishing dusky sharks stopped the direct plunder, but thousands of dusky sharks are still hooked every year by bottom and surface longline gear that’s supposed to catch other species, including grouper, snapper, tuna and swordfish. More than 80 percent of young dusky sharks and 40 percent of adults that are snagged on bottom longline gear die by the time the miles-long line of hooks is hauled back to the fishing boat. Around 30 percent of dusky sharks caught on surface longlines die. While these “by-caught” sharks have to be released, releasing a dead or seriously injured shark doesn’t do the population much good.

In fact, federal fisheries management law requires the National Marine Fisheries Service to do much more. The agency was required to cap the number of dusky sharks killed by fishing – including as wasteful bycatch – by 2010. They haven’t done it. The agency was required to end overfishing of dusky sharks by 2008, if not before. They haven’t done it. In fact, the Fisheries Service concluded that its current approach isn’t good enough to meet its own deadline for rebuilding the dusky shark population (which, mind you, is about a century away). That finding required the agency to implement more protective management measures to ensure that the dusky shark population would increase to a sustainable level. They haven’t done it.

Imagine if we allowed unlimited numbers of wolves to be killed by hunters who shot them accidentally while hunting deer or elk. That would be unacceptable. Allowing thousands of dusky sharks to be killed every year as a casualty of unsustainable fishing methods is equally unacceptable. If our oceans are to thrive, we have to protect the top predators that are key to maintaining ecological balance. That’s why we’re taking the Fisheries Service to court.

After wolves starting to return to healthy population levels in Yellowstone, scientists discovered just how intricately involved wolves are in maintaining healthy populations of prey species and how profoundly that trophic cascade affects the rivers and plants—the very habitat—that sustains the ecosystem. Scientists are just starting to understand how critical healthy shark populations are to sustaining vibrant coral reef ecosystems and other marine habitats. Imagine what more we might discover about the role of the dusky shark—big, beautiful, badass predator that it is—in sustaining our ocean ecosystems off the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It’s a discovery, a future, worth not only imagining, but fighting for.

As a senior attorney with the Oceans Program, Andrea's work focuses on protecting marine biodiversity and promoting abundant, resilient ocean ecosystems.

The California Regional Office fights for the rights of all to a healthy environment regardless of where in the state they live; we fight to protect the magnificent natural spaces and wildlife found in California; and we fight to transition California to a zero-emissions future where cars, trucks, buildings, and power plants run on clean energy, not fossil fuels.