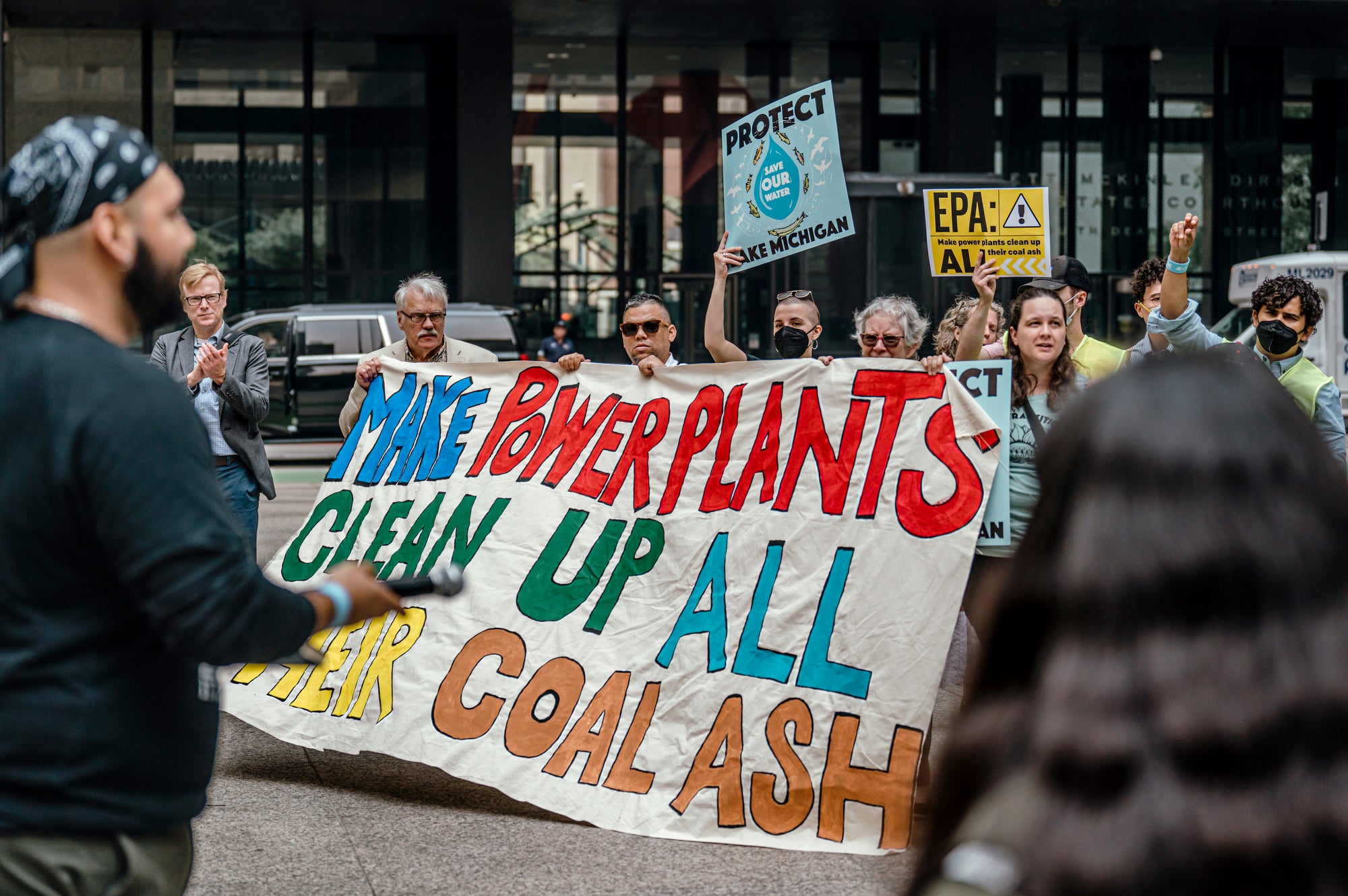

People Are Furious About Coal Ash Deregulation

Folks nationwide feel the Trump administration's EPA is abandoning its responsibility to protect communities, and they are speaking out.

Coal companies have dumped billions of tons of their toxic coal ash into leaking ponds, landfills, and random holes in the ground for more than a century.

Coal ash — the substance left after burning coal for energy — is a toxic mix of hazardous pollutants that have been linked to cancer, heart and thyroid disease, reproductive failure, and neurological harm. This toxic pollution can leak from dumpsites into groundwater, threatening neighboring communities.

After years of Earthjustice litigation and grassroots activism, the EPA finally established coal ash regulations in 2015 and strengthened protections in 2024. But now Trump’s EPA is systematically trying to gut these hard-won protections, and people from around the country are speaking out.

From Great Falls, Montana, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, all along the coast and throughout the heartland, and from red states and blue, people are tired of giving coal companies a free pass to pollute. In fact, 26,747 Earthjustice advocates sent comments to Trump’s EPA about one of its recent efforts to curry favor with the uneconomical and harmful coal industry.

As Earthjustice gears up for another round of litigation, their comments fortify us with the hope and resolve to keep fighting.

Here’s what they had to say.

Regarding EPA’s Responsibility

Many commenters urged the agency to prioritize its core mission: protecting people and the environment.

“The EPA should exist for the benefit of the environment and the people. Always.” – Patricia C.

“I’m a retired senior citizen living in Montana. We have a lot of experience with toxins left over from industries past and present. In many cases, the EPA is the only shield between us and environmental degradation and disease. We need you to be strong.” – Donna W.

“PLEASE CONSULT YOUR CONSCIENCE AND DO YOUR JOB: Protect the American people instead of the interests of greedy, selfish corporations.” – Amy A.

“Your mandate is to protect people, not appease the power companies.” – Michael S.

The now-closed Waukegan Generating Station, on the shore of Lake Michigan in Waukegan, Illinois. The coal fired power plant still has sizable coal ash ponds threatening the environment. (Jamie Kelter Davis for Earthjustice)

Choosing People and Planet over Profits

Others reminded the EPA that the health of the planet and duty to protect it for the next generation should come before corporate profits.

“I fail to see how allowing companies to continue to profit while communities continue to suffer does anything to make America great again.” – Wally B.

“We have one planet that we must not destroy with pollution. Do not ruin the only place we have to live! The profits of the few are not worth the destruction of our only home.” – Martha S.

“I want to live in a cleaner America and world. We need to think of the future we are creating and not just profits.” – Kathleen H.

“I believe that we need to think of the next five generations of people when we make decisions that have long-term effects.” – Connie G.

A truck is loaded with coal ash from the shuttered TVA Allen Fossil Plant in Memphis, Tennessee in 2022. (Brandon Dill for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Following the Science

Some pointed to the vast body of scientific research that shows how toxic chemicals in coal ash poisons ground and drinking water.

“From my reading on this topic, it doesn’t sound like there’s any quibbling around the science – we know that the toxins leak into groundwater, and poison people and the environment that use that groundwater.” – Susan L.

“Potable water is already becoming an issue as climate change has impacted our rivers, lakes and streams. Look no farther than the Colorado River for example. What will we drink when we’ve destroyed the sources of life-saving water?” – Barbara F.

“As a former high school biology teacher, I understand the importance of science in policy and decision making in our government…. It’s time to side with science, not with the polluting fossil fuel industry.” – John V.

“Every mom in America and around the world teaches her children to clean up their mess! It’s wrong to let polluters dirty our water, air, and land. It’s clean up time, EPA.” – Sarah L.

Coal ash wiped from the side of a home in La Belle Pennsylvania. (Chris Jordan-Bloch / Earthjustice)

From All Walks of Life

From Appalachia to the Midwest to the mountains, people from all across the country expressed how coal plants have harmed their health and local communities.

“This has been a long-term problem in my state of Virginia. Coal plants must be required to deal with coal ash responsibly. They have dragged their feet on compliance. Americans are watching whether this administration will be acting to protect us…or [allow] coal plants to backslide on their obligations.” – Margaret G.

“The coal burning plant near me has been polluting the city and surrounding area for decades. It finally closed, but the ponds remain. They are a hazard to drinking water, groundwater, and Lake Michigan.” – Mary M.

“I live in Miles City, MT, downwind and downstream from Colstrip, MT, home of coal power plants for almost 50 years. We have fought long and hard…for these reasonable rules to protect our health. This proposal is not only an insult to all of us concerned citizens but also puts us in clear danger again.” – Deborah H.

Earthjustice’s Clean Energy Program uses the power of the law and the strength of partnership to accelerate the transition to 100% clean energy.