Toxic Lead Is Still Contaminating Our Drinking Water, But Change Is Coming

After years of advocacy by Earthjustice and our partners, a newly updated EPA rule requires almost all lead pipes in the U.S. to be replaced within a decade.

This page was published a year ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

What to know:

- A newly updated EPA rule requires the replacement of most lead pipes nationwide within a decade.

- There is no safe level of lead exposure for children. Yet there are still more than 9 million lead service lines in the country, delivering drinking water to an estimated 22 million people.

- The new rule comes in response to successful lawsuits by Earthjustice and others, as well as advocacy by communities harmed by lead contamination.

- We are celebrating this victory, and we will keep fighting to get lead out of our lives. The EPA must now enact strong, proactive regulations that eliminate lead in drinking water at schools and childcare facilities, where children spend most of their day.

Queen Zakia Shabazz remembers the day she found out her 18-month-old son had lead poisoning.

It was 1996, and Shabazz was at the pediatrician’s office in Richmond, Virginia. During a routine exam, the doctor tested her son’s blood for lead. The test detected elevated levels.

“It just sent my family into a spin,” says Shabazz.

Though her son’s elevated lead levels were concerning, the doctor told her they weren’t high enough to justify medical therapy.

“It was basically like, ‘He’s poisoned. Just take him home,’” says Shabazz. “It opened up a whole new world of environmental injustice.” The frightening discovery angered Shabazz enough to prompt the founding of United Parents Against Lead (UPAL).

Shabazz knew she had to protect her children. She started researching the sources of lead exposure, which can include old paint, drinking water from lead pipes and plumbing fixtures, and contaminated soil. Children who live in older homes such as Shabazz’s are often exposed to multiple sources of lead throughout the course of their lives.

Top health experts agree that there is no safe level of exposure to lead, a toxic heavy metal that can permanently damage our bodies, and is especially dangerous to children while their brains are developing. As many as 22 million people drink water that passes through lead pipes. In addition, major lead contaminations have plagued the drinking water of multiple U.S. cities over the last several years, including Newark, New Jersey; Flint, Michigan; Washington, D.C.; Chicago, Illinois; and Buffalo, New York. Together, these cities serve as a harbinger of the broader lead crisis that may be unfolding across the nation, where more than 9 million lead service lines are buried — and many of them are slowly corroding.

Luckily, there’s never been a better opportunity to finally get the lead out of our drinking water. After years of advocacy backed by Earthjustice litigation, the federal government is mandating the replacement of most lead-based water lines in 10 years’ time — and has set aside billions of dollars to help pay for it.

Jacob Thomas, 6, of Flint, Mich., is held by his mother Alexis Taylor, as he gets his blood drawn in order to test his blood lead levels at Carriage Town Ministries in Flint, Michigan in 2016. (Brittany Greeson for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

“Taking Money Out of Your Pockets”

Lead service lines that carry drinking water have been recognized as a source of lead exposure since the late 1800s.

Yet many U.S. homes, businesses, and buildings still contain these lines, as well as lead-based faucets, plumbing fixtures, and pipe fittings. Together, they make up the biggest and most common source of lead in drinking water in the United States.

The reason why lead pipes are so common is a combination of regulatory ineffectiveness, a lack of quick fix options — and industry greed.

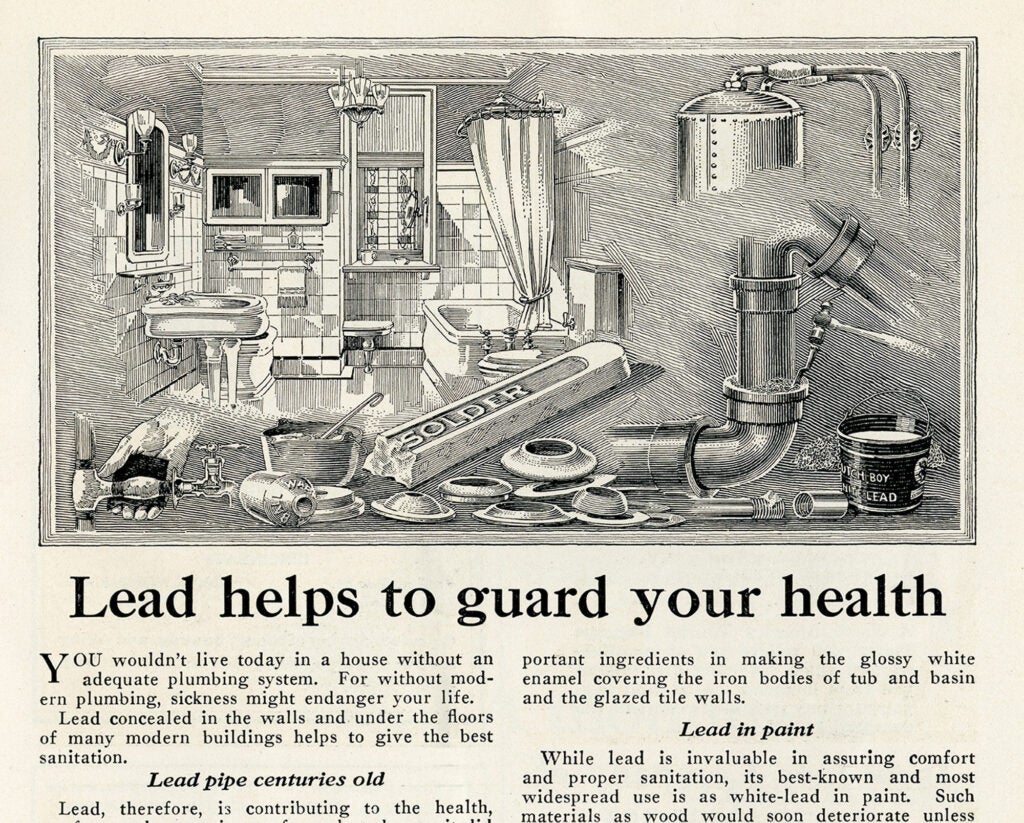

A magazine ad placed by the National Lead Company, in 1923. It was meant to reassure parents that lead paint was safe for children and families, even when evidence indicated otherwise. (Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine)

In the 1930s, amid growing public outcry over lead poisoning, the Lead Industries Association launched a decades-long campaign to push for the continued use of lead service lines to help protect their profits, according to investigative reporting by The Guardian. The association, made up of the major lead companies at the time, created a trade magazine and funded industry-friendly “research” to convince city leaders, regulatory agencies, and the public that lead was largely harmless. The industry is also responsible for labeling the lead issue as merely a “problem of slums,” exploiting longstanding racial tensions in the U.S. during that time.

Today, lead service lines can be found in every state. Several studies have linked lead exposure in children to permanent intellectual harms, along with behavioral and learning disorders. In adults, lead exposure may cause memory loss and reproductive impairments, and it is also a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease mortality. This widespread public exposure — which is entirely preventable — costs the U.S. economy over $50 billion every year in lost economic productivity resulting from reduced cognitive potential.

“Who Has a Voice, and Who Does Not?”

For years, Earthjustice has worked with community organizations to address and help alleviate the lead crisis, including Shabazz’s group, United Parents Against Lead. Recently, our litigation successfully pushed the Biden administration to take a critical first step in regulating leaded aviation fuel, as well as update hazard standards for lead in dust in residences and child-care facilities.

But progress on removing old lead pipes, which regulators officially banned the installation of in 1986, has been frustratingly slow. Despite the very public health crises in places like Newark and Flint, multiple administrations and sessions of Congress have declined to strengthen weak policies on lead in water and replacing lead service lines. Three primary reasons for inaction were federal and state agency neglect, water utilities downplaying and even hiding the presence of lead in public water systems, and Congress never allocating more resources for lead service line replacement.

In 2021, when the newly in place Biden administration announced that it would finally address the disproportionate health and environmental impacts that have long plagued vulnerable communities, tackling the lead pipe issue suddenly shot to the top of the priorities list.

To make a plan for replacing lead service lines, the federal EPA wanted to create a roundtable of people from impacted communities, non-governmental organizations, federal and state agencies, tribes, and other groups to discuss the issue. But when officials contacted Earthjustice Senior Legislative Counsel Julian Gonzalez to help bring folks to the table, they wanted only a handful of impacted communities.

“Talking to our partners, it was like, how are we supposed to choose only two or three places?’” says Gonzalez. “There are so many people from impacted communities whose lived experiences are the expertise desperately needed by the EPA.”

Gonzalez pushed hard for the EPA to host at least 10 different community roundtables, and the administration ultimately agreed.

While developing lists of possible participants with the help of community activists and other environmental advocacy groups, Gonzalez thought about his experiences growing up as a young Puerto Rican in New York City, as part of a family of teachers and social workers.

“I thought about the questions my parents taught me to ask, like ‘Who has a voice and who does not? Who has opportunity and who does not? Who dies, and who does not?’” he says.

Earthjustice legislative representative Julian Gonzalez, center, accompanies members of the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement to meetings on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C. (Melissa Lyttle for Earthjustice)

Over the next several months, Gonzalez and collaborators at other advocacy organizations created a multi-page spreadsheet of advocates who could push federal regulators to quickly enact a strong lead pipe replacement plan. The plan centered around a simple idea: the most effective and knowledgeable advocates are the people who bear the brunt of environmental injustice.

Earthjustice also partnered with the NAACP, which views the lead crisis as a long-neglected issue of poverty and racism. Though over half of all U.S. children have detectable levels of lead in their blood, Black and Hispanic children are more likely to have lead in their blood as compared to white children, and children in low-income households have higher lead levels in their blood than those in higher-income households. These disparities stem in large part from a history of redlining and racist segregation in the U.S. that pushed people of color and low-income families into neighborhoods with crumbling infrastructure like cracked lead paint and lead-based plumbing.

To solve this inequity, it’s important that the Biden administration sticks to its commitment to prioritizing frontline communities, says Abre’ Conner, the NAACP’s director of environmental and climate justice.

Abre’ Conner is the NAACP’s director of environmental and climate justice.

“Our current laws like the Safe Drinking Water Act are supposed to help people, but the data shows that Black communities and frontline communities are more likely to have unsafe drinking water,” she adds.

Earthjustice began representing the NAACP (as well as United Parents Against Lead and several other organizations) in court in January 2021, challenging the Trump administration’s attempt to further weaken the EPA’s historically ineffective regulations regarding lead in drinking water. Part of Earthjustice and the NAACP’s collaboration also included educating the NAACP’s members about why the existing regulations have failed to stop the lead crisis. NAACP members from across the country were eager to use this information as they submitted comments to the EPA on its new proposed rule in 2024, as well as advocated for stronger lead protections in their own communities.

“If we don’t have a focus on the historically polluted communities, then we’re going to continue to perpetuate environmental injustices,” says Conner.

A Solvable Problem

In 2024, after years of advocacy backed by Earthjustice litigation, the Biden administration unveiled a proposed rule that requires the replacement of “every lead pipe in the country” within 10 years as part of its vision for a lead-free future.

Successful lead pipe replacement programs around the country have proved this goal is reachable. In 2021, Newark, New Jersey, made headlines after the city tackled its lead water crisis by replacing nearly all of its 23,000 lead service lines with copper pipes in record time and paid for by the city.

This wasn’t a one-off miracle. States like Wisconsin and Colorado are also replacing their lead service lines, and they’re hoping that federal funding made available in the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal will help speed up the process. Allocated by Congress, the $15 billion for lead service replacement is the largest single investment in lead service lines in U.S. history.

The combination of federal funding and the EPA’s new rule will significantly speed up the process of nationwide lead service removal, ensuring that water systems are able to meet the mandated deadline. Earthjustice attorneys and our partners pushed for the rule to be as strong as possible, submitting more than 200 pages of comments to the EPA when the rule was still just a proposal. In its finalized form, the updated rule includes fewer exceptions and requires more frequent monitoring for lead in drinking water.

Zakia Shabazz, left, founder of United Parents Against Lead, stands alongside her husband Steve Shabazz, right, and Raymond Wilson, center, as they talk at UPAL’s Petersburg Community Resiliency Hub in Petersburg, Virginia. (Carlos Bernate for Earthjustice)

According to the EPA, the cost to remove about 9 million lead-based pipes across the country is estimated to be between $45 billion to $60 billion over a decade. The $15 billion “down payment” that the federal government set aside in the infrastructure bill (along with existing funds and financing at local and state levels) is a necessary first step in investing in the country’s long-term health. Once completed, the many health and societal benefits of the EPA’s rule will exceed its costs by a factor of 35:1, according to Harvard researchers.

“My son’s lead test was a wake-up call for me, and when there was a lead water crisis in Flint, it was a wakeup call for all of us,” says Shabazz of United Parents Against Lead, who is currently working with the government to prepare a proposal for addressing lead service line removal in Virginia. “We should finally heed that call.”

Originally published on March 11, 2024. This article was updated with news of the EPA's updated rule.

Earthjustice’s Toxic Exposure & Health Program uses the power of the law to ensure that all people have safe workplaces, neighborhoods, and schools; have access to safe drinking water and food; live in homes that are free of hazardous chemicals; and have access to safe products.