January 5, 2021

Sage Against the Machine

Saving the greater sage-grouse was one of the largest conservation efforts in U.S. history. When the Trump administration tried to sacrifice it to oil and gas, the bird’s champions flew to its rescue.

The sky, so the stories go, went dark like a rising storm.

Once numbering in the millions, the greater sage-grouse dominated the Western plains. According to historic records dating to the 1800s, when the bulky birds took flight, their numbers were so vast that they blocked out the sun.

Today, the grouse’s population is a fraction of its former size. It’s lost almost half of its original sagebrush habitat, which once encompassed over 150 million acres of the American West.

Of the “sagebrush sea” that remains, more than 90% is now crisscrossed by roads and power lines, overgrazed by cattle, pocked with oil and gas wells, charred by wildfires, or otherwise mutilated by humans. That’s bad news for a plant that does the hard work of keeping the West from drying out.

Things were tough enough for the sage-grouse and its home — then the Trump administration tried to do fossil fuel companies a favor by opening the bird’s territory up to oil and gas development. That’s when Earthjustice stepped in to show that the American West is not for sale. As part of restoring the grouse’s rightful protections, we successfully challenged the Trump administration’s plan to lease more than a million acres of public lands — a big victory for a big bird.

Locals readily tell tales of the old sagebrush kingdom, and the flamboyantly feathered bird that covered its plains.

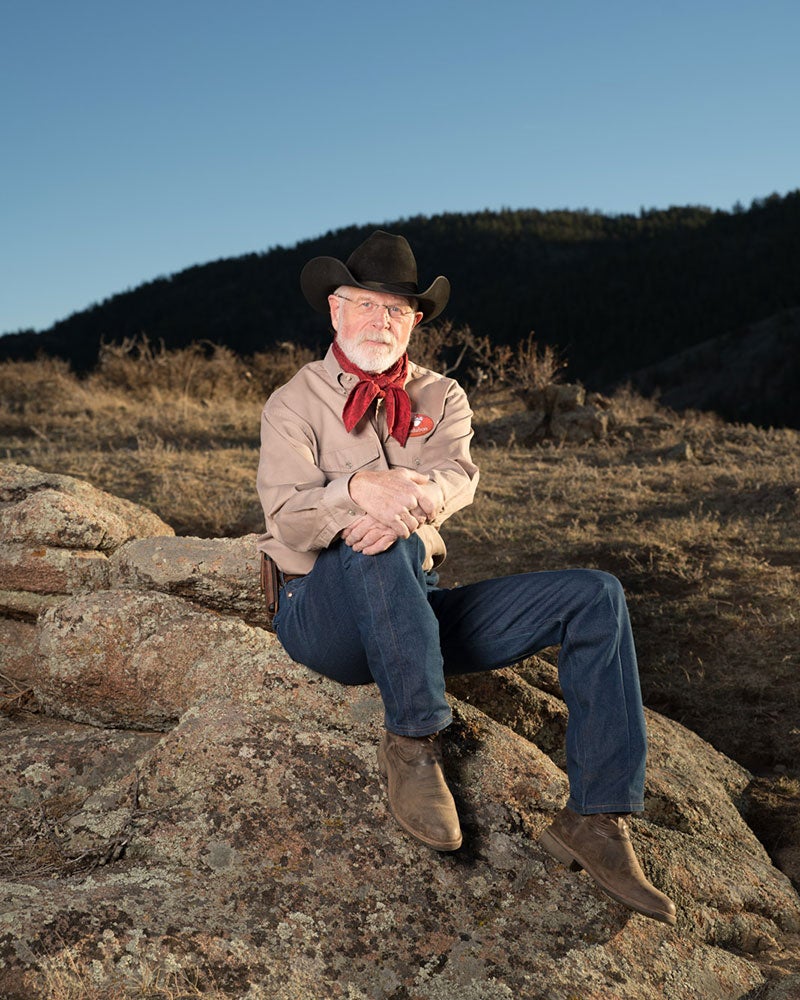

“The sage-grouse were the basis for survival in the West,” says Brian Rutledge, Central Flyway policy and conservation strategist at the National Audubon Society.

Typically sporting a cowboy hat, Rutledge raises cattle and horses at his ranch in the Colorado foothills (where he lives with his wife and four dogs). He knows more than a thing or two about sage-grouse, having worked with multiple administrations to protect them for over 15 years.

The sage-grouse is, in a word, extra.

The males’ luxurious white ruff, “Game of Thrones”-like spiked tail fan, and chocolate ombre plumage could rival any costume at the Met Gala. Their most distinctive feature is a pair of inflatable yellow air sacs that bulge from the male’s chest. During springtime mating seasons, the males vie for ladies’ attention by “lekking”: performing elaborate struts and inflating their air sacs in carefully synchronized pops. Ecologists have found that males who keep perfect popping harmony are responsible for the majority of the mating.

The parallels with humans aren’t lost on Rutledge. “Lekking birds are like bar scenes everywhere,” he chuckles.

Sage-grouse are inextricably tied to the sagebrush steppe ecosystem. They require a vast range and use every part of the land during their lifecycle: the bare steppes where males do battle for picky females, the shrub-sprouting uplands where hens nestle their eggs, and the lower riparian corridors where mothers raise their chicks.

“The mothers have fidelity to their nest location,” says Matt Holloran, a biologist who specializes in sage-grouse. “They go back to that spot year after year, until they die. Doesn’t matter if it’s burned or in the middle of a gas field.”

When tanker trucks roll in and oil wells begin pockmarking the steppe, the sage-grouse starts suffering fast. The birds are notoriously shy and become agitated around human traffic. Companies clear vegetation to make way for oil wells, depriving the grouse of food and safe cover. Tall infrastructure, like oil rigs or power lines, give an unnatural advantage to airborne predators like golden eagles. The grinding cacophony of daily fracking operations disrupts lekking rituals. And Holloran has observed that oil and gas development harms female sage-grouse the most, potentially due to environmental stressors that trigger them a constant fight-or-flight mode.

“I’ve watched populations plummet near oil and gas development, primarily driven by female mortality.” Holloran says.

As an “umbrella” species, the health of the sage-grouse’s population is an indicator of its entire ecosystem. If the birds are struggling, it’s likely that their namesake plant is too, and sagebrush plays a vital role in keeping soil moist across a region that can get less than 10 inches of rainfall per year. Without sagebrush’s moisture-retaining taproots, the shrubs and grasses that sustain hundreds of other species, like pronghorn antelopes and pygmy rabbits, would wither. So, a declining sage-grouse population is a bad sign for everybody.

In 2010, the federal government announced it would step in to save the bird. The grouse’s allies knew the plan would need to be ambitious — and it would need buy-in from everyone who had an interest in using the lands inhabited by the grouse. The government could just order ranchers and fossil fuel companies to stay off the sagebrush steppe, but the Obama administration aimed for the long game: a lasting, durable strategy for conserving the grouse.

As part of that process, conservationists met with every possible stakeholder, including groups they were more used to seeing from across a courtroom.

“I called it our Noah’s Ark,” says Rutledge. “You’d go into a meeting at the Bureau of Land Management, and there’d be two miners, two ranchers, two gas developers, two county council members, conservationists, and the agency folks. We kept expanding it as we found more disciplines that applied.”

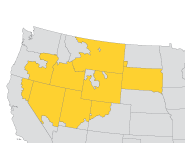

Finally, in 2015, the Obama administration signed off on a conservation plan that spanned 10 states: California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, North and South Dakota, Montana, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) made a commitment that any new oil and gas leasing in this region would prioritize land outside the grouse’s critical habitat.

Yet there was a flaw in the plan, which nearly unraveled this historic effort.

“Vulnerability to administration change was clearly its greatest weakness,” says Rutledge. “When the conservation methodology can change every four years, you can’t learn or conserve anything.”

In 2017, President Trump came into office determined to undo as many of his predecessor’s signature policies as possible. The administration has attacked dozens of conservation measures enacted under the Obama administration. (Earthjustice has fought many of these attacks, with an 80% win rate).

The Trump administration’s environmental agenda was heavily influenced by the oil and gas industry. In his first year, President Trump took a hatchet to the Department of the Interior, replacing longtime employees with fossil fuel representatives who’d supported his campaign. The industry was given a blank check to rewrite the country’s environmental protections to suit its needs.

The grand Obama-era sage-grouse plan was right in their crosshairs.

Following the Trumpian playbook, the Bureau of Land Management abruptly “reinterpreted” language in the plan that directed fossil fuel projects away from core sage-grouse habitat. It leased more than a million acres of federally protected land to oil and gas companies. Independent oil operators who had refused to sit at the negotiating table in 2015 were suddenly given a pirate’s ransom.

Even environmental defenders, who were expecting regulatory shenanigans from the new administration, were baffled by its attack on a plan that had broad buy-in across the West.

“Many of us were surprised they went after this,” says Nada Culver, the vice president of public lands at Audubon and a close advisor on the Obama-era plan. “There wasn’t a giant wave of companies demanding a rollback of the sage-grouse plan. The Obama administration had bent over backwards to show the industry that most of their best oil and gas resources are actually outside the protected areas. So this was an odd target.”

But the Trump administration was about to learn that ripping up a historic conservation plan to save the American West was a bad idea, because the sage-grouse had friends prepared to fight for it.

When Audubon and other conservation groups saw the lengths the administration would go to sacrifice the nation’s sagebrush habitat, they put in a call to Earthjustice.

“The people who worked on the 2015 plan put blood, sweat, and tears into protecting this bird,” says Earthjustice attorney Mike Freeman, who along with Tim Preso and Rumela Roy, represent the coalition that sued the government over its illegal leasing. Based in Denver, Colorado, Freeman has defended public lands in the Rocky Mountains West from oil and gas drilling for over a decade. But he was struck by how flagrantly the administration ignored the hard-won commitments made to protect the grouse.

“The new administration flat-out reneged on the promises BLM made and tried to just blow up the 2015 plan,” he says.

Freeman represents a diverse coalition of conservationists and sportsmen defending the grouse. “We worked with our clients to show that BLM’s aggressive oil and gas leasing was driven by an illegal policy decision: to ignore the commitments made in 2015,” he says.

In court, the coalition represented by Earthjustice focused their argument on how the BLM ordered its field offices to “reinterpret” a key protection of the 2015 plan, in a way that rendered it toothless. That direction opened the floodgates for massive oil and gas leasing across the sage-grouse’s range.

“The facts spoke for themselves,” says Freeman. “We were able to show how they violated the law and sacrificed the sage-grouse, just to pad the bottom lines of oil and gas companies.”

In May of 2020, the sage-grouse got a lifeline. The U.S. District Court of Montana sided with Earthjustice and conservationists, invalidating the government’s decision to disregard the 2015 plan. The court also nullified hundreds of the administration’s illegal oil and gas leases, bringing more than 330,000 acres back under protection. And in March of this year, the Montana court invalidated hundreds of additional leases that were sold illegally in the grouse’s protected habitat.

The battle to protect the sage-grouse isn’t done. The oil and gas industry and its government allies have appealed the 2020 ruling and are expected to appeal the March 2022 ruling. So, Freeman will be back in court to prove that protecting the sagebrush sea and its feathered icon, not oil and gas developers, is in the nation’s best interest.

For now, the win is a solid refusal by the courts to allow the U.S. government to turn its back on the greater sage-grouse. Across the steppe, thousands of synchronized pops, like champagne corks or a garish bird looking for love, will mark the victory this spring.

Originally published in the Earthjustice Quarterly Magazine.

Alison Cagle is a writer at Earthjustice. She is based in San Francisco. Alison tells the stories of the earth: the systems that govern it, the ripple effects of those systems, and the people who are fighting to change them to protect our planet and all its inhabitants.

Earthjustice’s Rocky Mountain office protects the region’s iconic public lands, wildlife species, and precious water resources; defends Tribes and disparately impacted communities fighting to live in a healthy environment; and works to accelerate the region’s transition to 100% clean energy.