May 12, 2021

Wildlife We’re Fighting For

Sustaining endangered wildlife has meant cleaning up waterways, improving pesticide protections, and preserving wild places. Wild creatures need these things. And we do, too.

The Endangered Species Act is wildlife’s best friend in an age of extinction. This visionary law protects and restores the species most at risk of extinction — 99% of the species it protects have survived. Earthjustice, born in the same era as the Endangered Species Act, has been at the forefront of efforts to ensure this critical statute realizes its promise.

Meet 16 of the hundreds of species Earthjustice has gone to court to protect.

Palila

A tiny bird breaks legal ground.

The palila lives exclusively between the elevations of 7,000 and 10,000 feet on Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi. (Aaron Maizlish / CC BY-NC 2.0)

Palila

Earthjustice’s pioneering work to stem the tide of extinction began in 1976, when a relatively new law known as the Endangered Species Act was used by Earthjustice attorney Mike Sherwood to save the endangered Hawaiian palila.

The story is told in “Breaking Legal Ground with a Tiny Bird and King Salmon”:

Alan Ziegler, a zoologist at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, related to Sherwood the sad plight of the palila, a small bird in the honeycreeper family, that lives exclusively between the elevations of 7,000 and 10,000 feet on Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi. It dines only on the seeds of the mamane tree, which is endemic to the same habitat. Meanwhile, feral sheep and goats, brought to Hawaiʻi for sport hunting, were destroying the trees.

Sherwood hit the law books and confirmed that the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which was new and not much explored, prohibited the “taking” of protected animals. This clearly meant hunting or trapping — but Sherwood thought he might be able to argue that destroying habitat vital to the survival of, in this case, the palila, which was on the list of protected species, might also constitute a taking and therefore be illegal.

Sherwood captioned the case, in a serious but somewhat whimsical stroke, Palila (Loxioides bailleui) v. Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources.

He named human coplaintiffs as well, and the state didn’t bother to challenge the standing of the bird. The newspapers — and several generations of law professors and students — loved it.

So did the judge, who ruled that the state must remove the animals that were pushing the palila to extinction. This decision set the important legal precedent that damaging the habitat of a listed species is illegal.

In the following years, until he retired in 2013, the legal work of Sherwood and his colleagues had a hand in protecting around 700 species, and much more.

Southern Resident Orca

Earthjustice’s legal work secured Endangered Species Act protections for the orcas in 2005. We continue to fight for their survival today.

L87 making a close pass at Saturna Parks sandstone shore, July 17, 2012. (Miles Ritter / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Southern Resident Orcas

Living in tight-knit matrilineal family units called “pods,” orcas (Orcinus orca), also known as killer whales, have one of the most complex social systems of all marine mammals. The Southern Resident orcas — the J, K, and L pods — were decimated in the 1960s and 1970s when they were targeted for live capture for the Sea Worlds.

Earthjustice’s legal work secured Endangered Species Act protections for the orcas in 2005. Patti Goldman, senior attorney of Earthjustice’s Northwest office, reminisces about the work:

The live capture practice ended when one of our clients, former Secretary of State Ralph Munro, was on a boat with his wife, and they found themselves in the middle of a live capture. They could hear the babies wailing as their mothers were captured and vice versa. That was a very pivotal moment. Munro, who was then a member of the state legislature, soon after became the lead proponent of a law banning live capture in Washington State waters.

The second decline occurred in the 1980s. There weren’t enough orcas of reproductive age because so many of them had been taken during the live capture.

The third decline is when Earthjustice got involved. In the 1990s there was a 20% decline, and the population was down to 78 individuals. This time, the orcas were declining because there wasn’t enough food (salmon) — and the food that did exist was often toxic. The situation had become a crisis, and it became clear that the orcas needed the protections of the Endangered Species Act.

Today, the southern resident killer whales are starving. The critically endangered population reached a 35-year low in 2019 — 73 individuals — a problem exacerbated by the fact that no calves born in the previous three years survived. In 2018, a mother orca known as J35 carried her dead calf with her for 17 days, in an extraordinary expression of grief. The calf had died several hours after birth.

Orcas are at the top of the food chain, so they ingest toxic contamination through their prey. Earthjustice has been identifying the key sources of toxic contamination, either to the orcas themselves or to their prey. The main source of new toxic pollution is stormwater runoff. Earthjustice has been working for many years to force better management of that runoff, particularly in urban areas. Setting a nationwide precedent, Earthjustice attorneys won a case that found low impact development such as green roofs and rain barrels is the best means of avoiding toxic runoff.

Earthjustice continues to work to protect the orcas, including from increased oil tanker traffic in the Salish Sea, and to restore the orcas’ primary food source — wild salmon.

Wild Salmon

Earthjustice has worked for decades to protect three endangered and threatened wild salmon species: king salmon, coho, and sockeye.

Jose Chi holds up an impressively large king salmon that was caught in the Pacific Ocean near Ft. Bragg, CA. (Chris Jordan-Bloch / Earthjustice)

Wild Salmon

By any measure, salmon are extraordinary creatures. They live in both saltwater and freshwater. They have nature’s best sense of direction. They are beautiful and delicious. They feed bears and other creatures besides humans. They are a barometer of the general health of both the ocean and of inland waters. They are, in the overblown prose of one magazine writer, the golden thread that stitches together land and sea.

That thread, alas, is frayed to the breaking point.

In 1991, the American Fisheries Society, an organization of scientists, estimated that of the once-abundant runs of salmon in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and California at least 106 stocks were extinct and another 214 were at high risk, moderate risk, or of “special concern.” Matters have not improved since then.

There are five major subspecies of salmon and some of the subspecies are differentiated by the season in which they spawn. Many of these stocks are now protected under the federal Endangered Species Act, mostly as a result of litigation by Earthjustice and others. Lawsuits by and large sparked the designation of critical habitat as well.

Earthjustice has worked for decades to protect three endangered and threatened wild salmon species, from California to the Pacific Northwest:

Chinook are known is the king of salmon for good reasons — the largest grow to 125 lbs. They can live up to seven years.

The shiny coho is also called silver salmon. They live 1–2 years in freshwater before migrating to sea. Coho were once one of the most commercially sought-after species.

The name for sockeye originates from the First Nation word sukkai, meaning “fish.” Sockeyes turn red as they migrate upriver and make the longest run of any salmon — 900 miles up the Columbia and Snake Rivers.

In the Pacific Northwest, the Columbia River Basin was once among the greatest salmon-producing river systems in the world. But all remaining Snake River salmon are facing extinction because four aging dams stand in their way to reaching their pristine, natal cold water streams in central Idaho and beyond.

Scientists say taking out the dams and restoring the river is the single best thing we can do to save the salmon. Earthjustice has worked for years to remove the dams.

Marbled Murrelet

It’s rare to see a nesting marbled murrelet. In 1992, Earthjustice gained endangered species protections for the birds. We continue to defend the old-growth forests they rely on from timber industry interests.

The marbled murrelet feeds at sea but nests only in old growth forests along the Pacific Coast. (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service)

Marbled Murrelet

By 1974, nesting behavior of all continental birds had been documented — except for the marbled murrelet (pronounced MER-let). Audubon Field Notes even offered a reward.

For observers, the seabird presented several challenges, not the least of which was that the bird alights for land under the cover of darkness, at 60 miles per hour. The marbled murrelet feeds at sea but nests only in old growth forests along the Pacific Coast.

But that year, tree surgeon Hoyt Foster happened to stop for lunch 148 feet up a Douglas fir — with an odd sight next to his boot. (“It looked like a squashed up porcupine with a beak sticking out.”) The animal exchanged looks with Foster — and latched onto his pruning saw. This first-observed nesting marbled murrelet chick was a feisty one.

Scientists would later find that murrelets don’t build nests, instead laying their single egg only when they can find a natural, moss-covered platform where the massive branches of old growth Douglas fir and redwood trees join the tree’s trunk.

Today, it’s rare to see a nesting marbled murrelet — and becoming rarer. Indiscriminate logging devastated the birds’ Pacific coastal old growth habitat. The murrelets were disappearing with these majestic trees.

Earthjustice has worked on behalf of the marbled murrelet since gaining federal endangered species protections for them three decades ago. In 1992, Earthjustice successfully fought to get federal endangered species protections for marbled murrelets and their habitat. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed marbled murrelets in Washington, Oregon, and California as a threatened species due to over-logging of coastal old growth forests.

Bowhead Whale

Earthjustice has successfully fought for years to prevent drilling in the Arctic Ocean, vital habitat for endangered bowhead whales, one of earth's oldest living mammals.

One bowhead whale was found to be 211 years old. (Amelia Brower / NOAA)

Bowhead Whale

Endangered bowhead whales thrive in narrow shelf waters. They live near the edge of moving ice pack, as it drops south in the winter and recedes north in the winter, for the bulk of the year, using their large skulls to break through thick ice when needed.

Bowhead whales are thought to use the reverberations of their calls off the undersides of ice floes to help them orient and navigate. And recent research has suggested that bowheads not only can smell (for example, dense aggregations of krill to feed on) — but that their sense of smell is even better developed than humans.

There is currently no offshore oil and gas development in the American Arctic Ocean, thanks in part to vigilant advocacy. Beginning in the George W. Bush administration, Earthjustice represented a coalition of Alaska Native and conservation groups in legal action to oppose new leasing and then exploration drilling. In several critical cases, we won injunctions that stopped drilling and forced reconsideration of the federal government’s plan to turn the Arctic Ocean into an oil field.

Building on our successful legal efforts, we undertook a campaign with our partners at the close of the Obama administration to put in place permanent protections for the Arctic Ocean. The administration responded with two important steps to preserve the Arctic Ocean in 2016. Under a law called the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, Obama permanently withdrew almost 120 million acres in the Arctic Ocean from drilling, leaving just 2% of the region open for development.

President Trump attempted to undo the withdrawal when he came into office. Earthjustice sued, and in a ruling issued from Anchorage in 2019, a U.S. District Court determined that President Trump overstepped his constitutional authority and violated federal law. The court ruling immediately restored permanent protections from drilling in those areas. It also prevented the imminent leasing of these sensitive areas to polluting fossil fuel corporations.

Earthjustice represented Alaska Wilderness League, Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, Greenpeace USA, League of Conservation Voters, Natural Resources Defense Council, Northern Alaska Environmental Center, REDOIL (Resisting Environmental Destruction on Indigenous Lands), Sierra Club, The Wilderness Society. Natural Resources Defense Council is co-counsel.

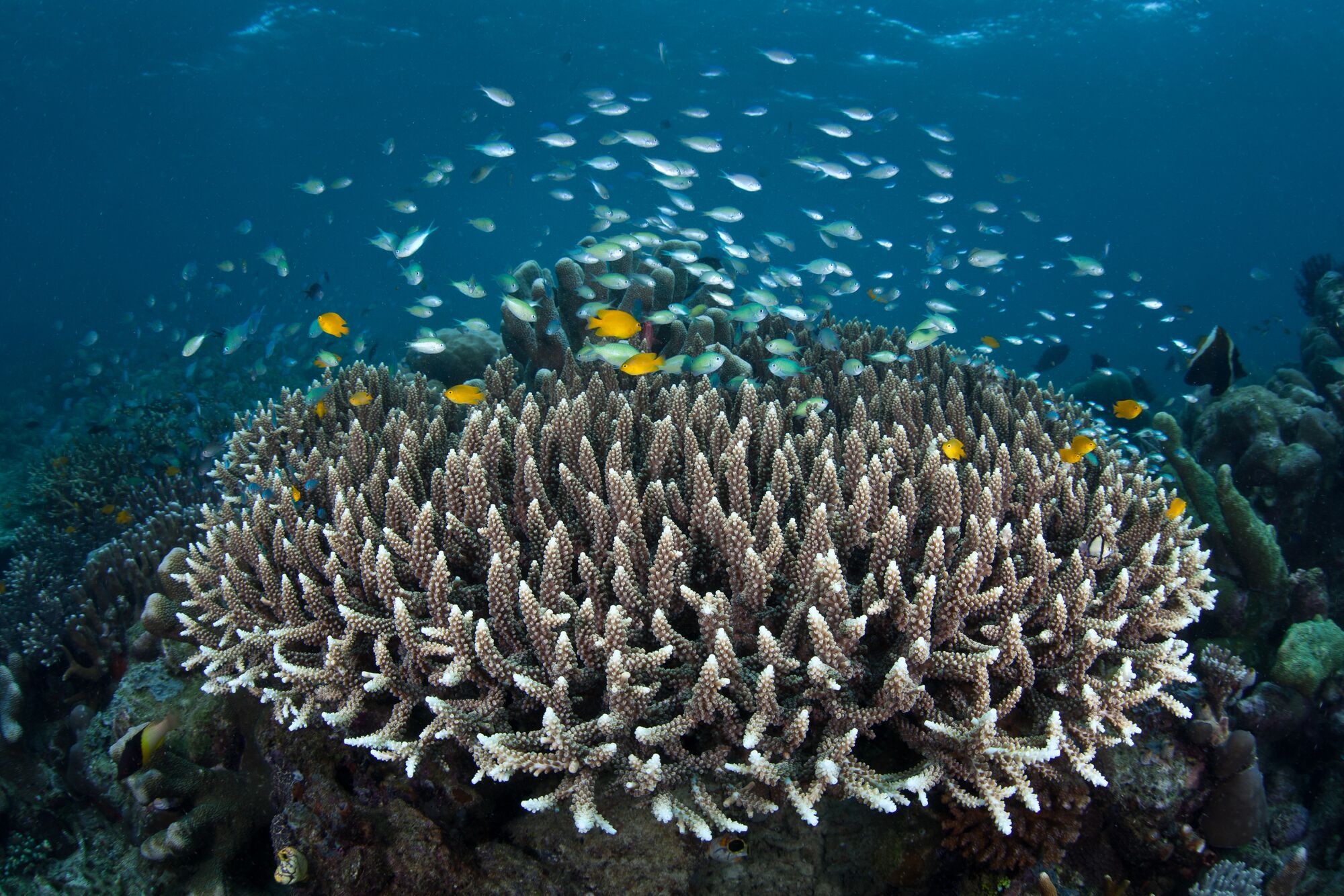

Staghorn & Elkhorn Corals

Not long ago, these were the main reef-building coral species in the Caribbean. Earthjustice won a lawsuit in 2014 to better protect the endangered coral by protecting the fish they rely on: the hard-working parrotfish.

Small mouth grunts swim past elkhorn coral. (Ethan Daniels / Shutterstock)

Staghorn & Elkhorn Corals

For fish, coral reefs serve as nursery and breeding grounds, food supply, and protection from predators. When coral reefs collapse, the health of every species that depends on them is imperiled.

Disease, pollution, algae overgrowth, and acidification due to climate pollutants have all played a role in harming Caribbean coral. Protecting coral reefs from local threats such as excessive fishing is critical to ensuring that they can withstand other, global threats.

In 2012, Earthjustice filed a lawsuit in federal court seeking to ensure that the National Marine Fisheries Service gave these corals and their reef habitat in the Caribbean the protections they are due under the law.

The National Marine Fisheries Service is in charge of conserving resources that belong to everyone, including coral reefs in U.S. waters. Read about the story in Coral and Parrotfish: The Fight for Recovery:

When Jacques Costeau’s film crew first captured the beauty and abundance life among Caribbean coral reefs, we fell in love with the ocean.

Today, many of those same reefs are collapsing. Once vibrant coral reef ecosystems look like rubble fields. The fish are few, and algae has smothered and killed the reefs.

Not so long ago, elkhorn and staghorn corals were the main reef-building coral species in the Caribbean. Yet these species have declined by as much as 98% since the 1970s thanks to stressors including overfishing, disease, and climate change. As the corals decline, so does quality habitat for fish and other creatures.

There is still hope we can save them. Given protection, coral reefs can regrow. We must reduce those things that harm coral and increase the things that help coral recover.

And one way to help Caribbean coral is to protect the janitor of the coral reef, the colorful, hard-working parrotfish.

The Earthjustice lawsuit claimed that the Fisheries Service had allowed unsustainable fishing despite science showing that parrotfish and other grazing fish play a key role in promoting the health of coral reefs. By allowing the targeted fishing of parrotfish without any effective system for tracking and limiting the impacts of that fishing on corals, the government was violating the Endangered Species Act.

In 2013, the court ordered the agency to redo its monitoring plan to ensure that the agency can detect and prevent harm to staghorn and elkhorn coral caused by fishing.

Wolverine

The continued existence of wolverines give hope that there’s still a chance for our wild world to thrive, not merely survive, into future generations. Earthjustice works to establish protections not only for wolverines, but also for the integrated ecosystems that sustain their prey and habitat.

A wolverine moves through the shadows of subalpine fir lit by alpenglow, in the Northern Rockies. (Steven Gnam)

Wolverine

He once summited Mt. Cleveland, the highest peak in Glacier National Park, in the dead of winter, clearing the last 4,900 feet in less than 90 minutes.

He once broke into a trap with log walls eight inches thick — to pick a fight with an unlucky rival sitting inside.

He once had three girlfriends. At the same time. And survived.

Even among a species renowned for a near unbelievable combination of toughness and wanderlust, M3’s exploits are legendary. He is, according to biologist Doug Chadwick, “a wolverine’s wolverine.”

Wolverines, the largest land-dwelling members of the weasel family, once roamed across the northern tier of the United States and as far south as New Mexico in the Rockies and Southern California in the Sierra Nevada range. The wolverine’s hallmarks are an equal opportunity approach to eating (fresh-dead to long-dead are all acceptable) and a disproportionate dose of attitude (they don’t think twice about stealing food from grizzlies).

Wolverines disdain human encroachment. But places where humans have not left their mark are dwindling. Habitat fragmentation, development, and climate change have taken a heavy toll. Estimates place fewer than 300 wolverines in small, fragmented populations in Idaho, Montana, Washington, Wyoming, and northeast Oregon.

For more than two decades, Earthjustice has worked to establish protections not only for the species, but also for the integrated ecosystems that sustain their prey and habitat. Far-ranging legal work to protect wildlife corridors in the Crown of the Continent, multi-case efforts to preserve millions of acres of roadless land, and minimizing impacts of off-road vehicles will all play roles in preserving the balance necessary for the wolverine.

M3 had ascended Mt. Cleveland via an inhospitable route eschewed by humans and mountain goats alike. The following June, experienced climbers eagerly took on the challenge of duplicating his feat. But it became apparent that Mt. Cleveland’s south face doesn’t do summer. Near vertical walls of compacted snow persisted, and the route remained M3’s alone.

Wolverines are harbingers of the greater health of the complex ecosystems we all depend on — ecosystems humans are rapidly remaking, by bulldozer and by carbon pollution. The continued existence of wolverines give hope that there’s still a chance for our wild world to thrive, not merely survive, into future generations.

As Earthjustice's Northern Rockies-based attorney Tim Preso explained: “The presence of the wolverine tells us that the landscape is productive not only for the wolverine, but for lots of other creatures that also require that kind of landscape: the fish, smaller mammals — and ultimately, us.”

California Sea Otters

Once thought to be extinct, until a small colony was discovered in 1938. Earthjustice successfully defended the end of the ill-advised “No Otter Zone,” which excluded otters from parts of their habitat. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which allowed the decision to stand by declining to review the appeal.

Sea otter dines on crab. (Jean Edouard Rozey / Shutterstock)

California Sea Otters

As with the wolverine, the fur trade nearly turned every last otter into luxury winter wear. Once found in abundance, sea otters were thought to be extinct until a small colony was discovered in 1938 near Big Sur. Since then, it’s been a slow, uncertain recovery.

Sea otters are a keystone species — the lynchpin of ecosystems. When otters feed on shellfish, particularly sea urchins, they control the population of these species. Otherwise, urchins could consume all of the kelp in the otter’s coastal habitat.

Who doesn’t like sea urchin-slurping, abalone-loving otters? The shellfish industry, which has its eye on selling those same bounties to urchin-slurping, abalone-loving humans.

To make the otter population more palatable to Southern California shellfishers, the “No Otter Zone” — encompassing most of the otters’ historical southern range — was created.

For years, clandestine abductions took place along the Southern California coast. Teams of divers prowled the Pacific, patiently waiting — waiting for their furry targets to fall asleep.

In their sights were California sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis), who didn’t get the memo that Point Conception to the Mexico border was a certified “No Otter Zone.”

Divers cruised the coastline, seeking wayward otters who dared to cross the invisible “no otter” line. Divers waited for the skittish otter to nod off and drop its guard. Nabbed otters were packed off to San Nicolas or up the coast. The whole operation cost an estimated $10,000 per otter. And often the dispatched otters — those who survived — would swim right back down the coast.

On behalf of the Humane Society of the United States, Friends of the Sea Otter, Defenders of Wildlife, and Center for Biological Diversity, Earthjustice defended the end of the ill-advised “No Otter Zone.” The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which allowed the decision to stand by declining to review the appeal.

California sea otters were once thought to have been driven out of existence, gone the way of the dodo and passenger pigeon. But, thanks to the hardy few who survived humankind’s voracious appetite centuries ago, we — and the otters — now have a second chance.

Yellowstone Grizzly Bear

One of the last strongholds for grizzlies is Yellowstone National Park and its surrounding public land. Earthjustice attorneys have worked for decades to safeguard the bears.

A small blade of grass in the corner of her mouth, this young grizzly takes a break from grazing to survey the meadow along Pilgrim Creek. (Thomas D. Mangelsen)

Yellowstone Grizzly Bear

During Lewis and Clark's famous expedition across America's vast western wilderness in the early 1800s, there were approximately 50,000 grizzly bears. Today, grizzly bears in the lower-48 states are reduced to 1% of their historic range and 1–2% of their historic numbers due to persecution, poisoning, sport hunting, and habitat destruction.

One of the last strongholds for grizzlies is Yellowstone National Park and its surrounding public land. This unique region is one of the few remaining great ecosystems of the world.

Identifiable by its distinctive shoulder hump, long, curled claws and the grizzled tips of its fur, the mighty grizzly bear also has a terrific sense of smell and can run at speeds of up to 30 miles per hour. In Alaska and other coastal areas they gorge on salmon runs every summer and fall. But the bears in the Yellowstone region have no salmon and must survive by eating a diet primarily of grasses, bulbs, bugs, elk, trout — and especially the seeds of the whitebark pine tree.

The highly nutritious seeds are chocked full of fat and protein, and when available, are eaten by the thousands by Yellowstone grizzlies. But warming temperatures have enabled mountain pine beetles to kill high-altitude whitebark pine trees at alarming rates, reducing the seed supply. In an ecosystem where all life is interrelated and connected, the decline of one life form can precipitate the decline of another.

Earthjustice has worked for decades to safeguard Yellowstone’s grizzlies — including challenging attempts in 2007 and 2017 to remove federal protections. Earthjustice attorneys methodically documented the decline of whitebark pine trees and demonstrated the importance of the food source to the grizzlies, using the government's own studies.

Earthjustice attorneys were in court again in 2020, successfully defending endangered species protections for the bears.

Gray Wolf

In 1973, gray wolves became one of the first animals to appear on the Endangered Species list. Earthjustice has gone to court on behalf of wolves throughout the country.

A wolf in Lamar Valley, Yellowstone National Park. (Robert Warrington / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Gray Wolf

The gray wolf is one of North America's most iconic native predators. The incredible comeback of the gray wolf in the Northern Rockies signaled the resolve of a society strong enough to embrace a world ensured not just for us, but for all species.

Decimated by decades of unregulated slaughter and persecution, gray wolves were pushed to the brink of extinction. In 1973, gray wolves became one of the first animals to appear on the Endangered Species list.

The stories of individual wolves, chronicled by wolf watchers and biologists, provide fascinating glimpses into a complex and highly social species.

“Limpy”: Known for his distinctive three-legged gait, “he was a hell of a wolf,” recalled one veteran wolf-watcher. And on March 28, 2008, he was shot dead.

“Journey”: Born in northeastern Oregon, he struck out on his own on an epic trek that would bring him to California — the state's first wild wolf seen in nearly a century.

“Spitfire”: During the summer months of 2015, she led Yellowstone's Lamar Canyon Pack in a gripping saga of strategy, strength — and hope.

Today, the future of wolves remains under threat — from hostile state management plans to anti-wildlife politicians.

Earthjustice has gone to court and advocated on behalf of wolf populations throughout the country, alongside our partners and clients, for more than a decade. The Trump administration removed protections for wolves across the entire contiguous United States. Earthjustice is challenging the decision in court.

Florida Panther

The panther’s last remaining territory on Earth is in south Florida. We’re in court to ensure these magnificent creatures can survive.

A Florida panther at White Oak Conservation Center, Florida. (Frans Lanting / National Geographic)

Florida Panther

The state animal of Florida, these big cats have been on the federal endangered species list since 1967.

Vehicle collisions are the leading cause of death for Florida panthers — nearly 85% of panther deaths are on roadways.

In January 2020, Earthjustice filed a federal lawsuit in Florida’s Middle District to challenge road widening projects on State Roads 29 and 82 in Collier, Lee, and Hendry Counties, because they would endanger our official state animal, the Florida panther.

“We’re going to court because we don’t want this to be the last generation of Floridians to ever see a wild Florida panther,” said Earthjustice attorney Bonnie Malloy. “We need to uphold the national environmental laws that are in place to prevent that.”

Florida panther mother with kittens. (Florida Fish and Wildlife)

North Atlantic Right Whale

Even a single death is a threat to the survival of this species. Earthjustice recently won a lawsuit to bar the use of entangling nets in their habitat. Entanglement in fishing gear is the leading threat to right whales.

The New England Aquarium has pioneered creative methods to aid North Atlantic right whale research: scat-sniffing dogs. From the bow of the boat, the dogs "tell" their handlers which direction the scat lies. The whale scat samples help scientists study right whales' reproduction and health trends. Above, Fargo greets one of the study’s subjects. (Photo courtesy of New England Aquarium)

North Atlantic Right Whale

Distinct "v-shaped" spout patterns spray a dozen feet into the crisp ocean air — a sure sign that right whales have returned to calve off the coasts of Florida and Georgia. The few remaining whales come each spring, sometimes swimming close enough to spot from shore.

Scientists estimate that only 300 to 400 of these whales remain. Although listed as endangered in 1973, the North Atlantic population of right whales has made little progress towards recovery.

The right whales' very name suggests why they were hunted to the brink of extinction. Whalers in the 18th century thought of them as the "right" whales to hunt. They were easy to spot from shore, floated to the surface when killed, and provided a bounty of oil and meat.

Today, although no longer hunted, right whales are still victims of human activity. Because their calving grounds and habitat stretch through some of the busiest shipping channels and fishing spots in the world, right whales are often struck by passing ships or become entangled in fishing gear.

In 2019, in response to litigation brought by the Conservation Law Foundation and Earthjustice, a federal court ruled that federal fisheries managers failed to protect critically endangered North Atlantic right whales when opening nearly 3,000 square miles of previously protected New England marine waters to dangerous fishing gear. Earthjustice has worked to defend the whales for years.

Entanglement in fishing gear is the leading threat to right whales, and the National Marine Fisheries Service has stated that even a single death is a threat to the species’ survival.

ʻUaʻu (Hawaiian Petrel)

Once plentiful throughout the Hawaiian islands, they are colliding with human development, killed when they fly into power lines and become disoriented from bright streetlights. Earthjustice attorneys are working to change that.

A Hawaiian petrel chick. The birds spend the majority of their lives out over ocean waters and return to land only to breed. (Andre Raine / U.S. FWS)

ʻUaʻu (Hawaiian Petrel)

The mysterious, rarely seen ʻuaʻu, also known as the Hawaiian petrel (Pterodroma sandwichensis), are true seafarers, living nearly all of their lives over the open ocean.

Earthjustice has been working for years in the Aloha State on behalf of these endangered birds. Once plentiful throughout the islands, they are colliding — literally — with human development, killed when they fly into power lines and become disoriented from bright streetlights.

Petrels were named after St. Peter. They both walk on water (sort of). The name ‘petrel’ is commonly thought to have originated from the French version of St. Peter’s name. The birds have long, thin legs, which don’t work too well on land, and several species will slightly dip their feet into the water and seemingly hover while feeding, giving the illusion that they are walking or standing on the water’s surface.

Petrels are pelagic birds, meaning that they spend the majority of their lives out over ocean waters and return to land only to breed. If you’re lost out on the open ocean and you see a petrel, chances are, you’re not any closer to land than before the bird appeared.

Even when the petrel is nominally back on solid ground, scientists have found that they will fly over 6,000 miles on two-week foraging trips — even all the way to Japan — to find food for their young.

During the months that they spend out on the ocean, Hawaiian petrels will feast on squid, fish, plankton, and crustaceans. And when they get thirsty, tubes in the petrel’s specially adapted bill allow them to “sneeze” out the salt from seawater.

At around six years of age, Hawaiian petrels will begin returning to Hawaiʻi annually to breed, laying a single white egg each year. For the next 40 years, they will go back to the same nest site. That Hawaiian petrels generally lay only one egg a year (with no guarantees that the chick will survive to adulthood), and take six years to even start the process, is one reason why the population of this unique bird is so vulnerable once the adult population has taken a dip.

In March 2020, a court ruling in a lawsuit brought by Earthjustice found that Maui County violated state law by failing to conduct environmental review for a streetlights project that threatens harm to Maui’s imperiled sea turtles and seabirds, including Hawaiian petrels.

For years, wildlife experts and community members warned the county that streetlights that emit a high amount of blue light can disorient these species, urging the county to use LED fixtures that filter out blue light, like the streetlights used on Hawaiʻi Island

“The county gave no thought to the law or environmental impacts before plowing forward full-speed with the streetlights project,” said Earthjustice attorney Kylie Wager Cruz. “This is precisely the type of reckless decision-making that our environmental review laws were designed to prevent.”

Under a court-ordered stipulation, before the county can proceed with the streetlights project, it must first complete the public environmental review process mandated by HEPA, beginning with an environmental assessment. Following the ruling, the court is expected to address the citizen groups’ further request for a court order mandating the installation of filters to reduce blue light on the 947 LED streetlights that were illegally installed without any environmental review. Earthjustice is representing Hawaiʻi Wildlife Fund and Conservation Council for Hawaiʻi.

Graham’s Beardtongue

A wildflower’s existence — part of a rich, complex ecosystem — is threatened when fossil fuel energy developers eye its sole habitat. Earthjustice attorneys have gone to court twice to ensure protections for this rare species are based on science, as the law requires.

Graham's beardtongues (Penstemon grahamii) are threatened by fossil fuel energy development interests and impacts from loss of pollinators, climate change, and more. (Kevin Megown / U.S. Forest Service)

Graham’s Beardtongue

Graham’s beardtongues live only on oil shale outcroppings in northeastern Utah’s Uinta Basin and northwestern Colorado.

The “badland” region (characterized by rocky terrain and varied geologic formations) is home to dozens of rare plants found nowhere else in the world and supports a complex ecosystem, including mule deer, elk, antelope, mountain lions, and black bears.

Along with the White River beardtongue, the two wildflowers have been waiting for Endangered Species Act protection for decades. The threats to their continued existence have only increased as developers have flocked to Utah hoping to exploit oil shale and tar sands deposits.

On behalf of our clients, Earthjustice has successfully gone to court twice to protect this species from the threats of fossil fuel energy development and impacts from loss of pollinators, climate change, and more.

In the most recent lawsuit, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to protect the White River and Graham’s beardtongues in 2013 after determining that 91% of Graham’s beardtongue populations and 100% of White River beardtongues were threatened by the impacts of oil and gas development. When the agency abruptly reversed course and withheld protections, Earthjustice challenged the decision on behalf of our clients.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado agreed with us in 2016, finding that the agency did not base its decision solely on the best available science, as required by the Endangered Species Act. The court vacated the decision not to list and reinstated the proposed rule.

Bald Eagle

Successfully graduated from the Endangered Species list in 2007, but threats remain. Earthjustice opposed the short-sighted approval of a hardrock mine in Alaska, which threatens the Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve, where thousands of bald eagles gather.

A bald eagle. (Mark Dumont / CC BY-NC 2.0)

Bald Eagle

It was once possible that this most American of birds could vanish forever. Due to widespread hunting, poisoning, habitat destruction, and the devastating effects of the pesticide DDT, the eagles had disappeared from many parts of the country where they once thrived.

But the bald eagle became an Endangered Species Act success story, and our national icon successfully flew off the Endangered Species list in 2007, having recovered from a low of 417 known nesting pairs in 1963.

Thanks to the strong protections of the Endangered Species Act and other safeguards in the intervening decades — including safeguards for prime eagle habitat and work to bring the birds back to areas where they had disappeared as well as the eventual nationwide banning of DDT — there are now more than 100,000 bald eagles in the entire United States.

Although the bald eagle is no longer endangered, the species still faces many threats. One of those is in Alaska, where the proposed Constantine Mine threatens the Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve, where thousands of bald eagles gather to feast on the last runs of coho and chum salmon — a globally unique phenomenon.

A bald eagle lands in the snow at the edge of the Chilkat River, near Haines, Alaska. In this area is the Alaska Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve, where thousands of bald eagles gather to feast on the last runs of coho and chum salmon—a globally unique phenomenon. (Sergei Uryadnikov / Getty Images)

Represented by Earthjustice, the Chilkat Indian Village of Klukwan, Southeast Alaska Conservation Council, Lynn Canal Conservation, and Rivers Without Borders took the Bureau of Land Management to court, arguing that the agency’s approval of a mining exploration plan for Constantine Metal Resources, Ltd., violates federal law by refusing to consider in any way the impacts of potential mine development on the sensitive watershed.

Full-scale mine development to extract metals-bearing rock is a process that has the well-documented and all-too-frequent consequence of releasing toxic heavy-metals pollution and acidic water into the surrounding environment.

The watershed, which includes the Klehini River, provides spawning grounds for all five species of Pacific salmon, as well as anadromous eulachon and trout. The Chilkat River watershed is especially vital to the Chilkat Indian Village of Klukwan. The river, with its abundant salmon population, is the economic and cultural lifeblood of the village and the Chilkat Tlingit people who have called it home for at least 2,000 years.

Gulf Sturgeon

From cat-sized salamanders to humpbacked fish, all species play a critical role in the larger ecosystem. In the case of this sturgeon, a lawsuit Earthjustice brought in 2001 achieved not only expanded protections for the imperiled fish, but set the stage for far-reaching benefits for many other endangered species.

One of the oldest existing fish species, the Gulf sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi) is considered by experts to be a remarkably even-tempered fish. (Kayla Kimmel / U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service)

Gulf Sturgeon

It isn't easy being a Gulf sturgeon. Trout are prettier. Even catfish are more cuddly. But there's one thing the sturgeon has that his neighbors don't — a friend in court.

In 2001, Earthjustice won additional protections for the fish, which was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1990. The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals threw out a decision reached by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service refusing to protect habitat in which the fish lives. The court invalidated a commonly used regulation that had been used in hundreds of prior cases to narrow protections granted rare species by the Endangered Species Act.

"This is a far-reaching case that could easily translate into much greater protection for endangered species," said Robert Wiygul, the Earthjustice attorney who litigated the case, at the time of the decision in 2001.

"This decision is a return to the original intent of the Endangered Species Act — to recover species and move them off the list. The Endangered Species Act has been criticized for not recovering enough species, but this decision tells us the Act has never been given a fair chance."

The Gulf sturgeon can reach 500 pounds and live almost 50 years. It is one of the few anadromous fish species (sea fish that breed in fresh water) in the Gulf of Mexico. Once ranging from the Florida Keys to the Mississippi River, the population is now confined to only four rivers: Pearl River in Louisiana, Pascagoula River in Mississippi, and Apalachicola and Suwannee Rivers in Florida.

Although once common enough to support a commercial fishery, sturgeon were pushed to the brink of extinction by overfishing, water pollution, and dams that destroyed their habitat.

One of the oldest existing fish species, sturgeon populations are disappearing from their habitats worldwide. In old English law, sturgeons were considered royal fish that, if caught on or near the shore, became property of the king. The Gulf sturgeon is considered by experts to be a remarkably even-tempered fish.

Today, the Endangered Species Act itself is under attack.

In 2019, the Trump administration finalized dramatic rollbacks to the rules that implement the Endangered Species Act, attempting to weaken the law that serves as the last safety net for animals and plants facing extinction. The changes imperil hundreds of species and violate the spirit and purpose of the law itself.

On behalf of environmental and animal protection groups, Earthjustice challenged the new regulations.

In writing the Endangered Species Act, the Congress of 1973 realized that, for this law to work, citizens needed to be able to go to court to uphold its provisions. Like all laws, the Endangered Species Act is only words on paper — unless it is enforced.

With the Endangered Species Act, we have acted in the interest of hundreds of plants and animals to ensure their survival. But that is not all.

Sustaining endangered wildlife has meant cleaning up waterways, improving pesticide protections, and preserving wild places that provide a long-term, low-cost source of clean air and water and offer a quiet refuge in our increasingly noisy, crowded world.

Wild creatures need these things. And we do, too.

By preserving endangered species, we help to preserve ourselves.